AHIMSA – THE MARTIAL WAY

This article will attempt to expound on why Ahimsa can be truly understood with the practice of the martial arts, specifically armed combat. It will attempt to analyze why Ahimsa has nothing to do with either a lack of violence or a lack of fighting (combat). This article will in essence try to show how Ahimsa can be practiced and expressed most effectively through fighting and how it is a “state of existence during a fight”.

Ahimsa is sometimes translated as “non-violence”. But this seems an inadequate translation. If one is well versed in the vernacular in India, it is easy to realize that “Ahimsa” is the description of a situation which DOES NOT involve “Himsa”. “Himsa” is not “violence”. It is any situation that involves discomfort or any situation that puts you in trouble. Thus, “Ahimsa” becomes “not causing or giving trouble” to anyone.

The popular expression, “Ahimsa paramo dharma”, based on the above definition of “Ahimsa” boils down to “Ensuring you do not cause trouble to others is an important responsibility”. This of course is not a direct translation, more like something that captures the essence of the expression. Martial Arts in its truest form is about strategic positioning (Kurai Dori in Japanese). Being in the right position, in both space and time is what exposes an opening in the opponent or reveals a new weakness in the opponent. The importance of strategic positioning is of course heightened in armed combat considering the human effort needed to cause harm to an opponent is outsourced to a weapon.

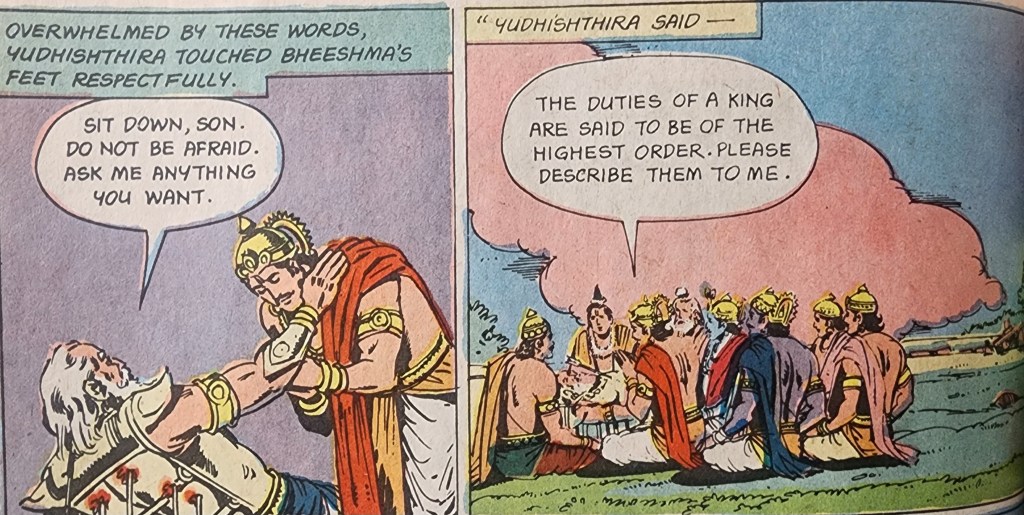

Yudishtira learning from Bheeshma. A question asked by Yudishtira during this episode is where the phrase “Ahimsa Paramo Dharma” originally comes from, to the best of my knowledge. Image credit – “Mahabharata 4 – Yudishtira’s Coronation” published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Strategic positioning is in turn a consequence of consistent and concurrent response generation to an opponent. One needs to remember that we consider a “response” and not a “reaction” to what an opponent does. However, it is a response that involves experience and “mindfulness”, and not a result of analysis (which leads to a “full mind” and not “mindfulness”).

To be in the right position is what strategic positioning means. To be in the right position, one must of course MOVE. This movement of the entire body to put it in the most advantageous position in a given situation is what is called Taihenjutsu in Japanese (Taijutsu is slightly different).

Taihenjutsu when layered with strikes (either with fists or blades or anything else), locks, breaks and throws leads to other forms like Daken Taijutsu (any martial art that involves hitting or striking) and Jutai Jutsu or Kosshi Jutsu (any martial art that involves restraining, locking, choking or throwing). Of course Koppo Jutsu is a specialization of Daken Taijutsu. As any martial arts practitioner would know none of these art forms exist by themselves and are always used together, except in sports where specific rules prevent the same for safety reasons. Thus, Taihenjutsu is the base on which martial art forms are built. It is the absolute core.

It is also true that as martial artists advance in age and experience, reliance on strength and speed reduces both due to the aging of the body and the realization through experience that expending any energy more than what is absolutely necessary in a combat situation is wasteful. Only the energy needed to survive a situation and escape might be needed in most situations of conflict. Also, with age, the glee or “high” of a fight generally reduces.

With a reduction in strength and speed, the necessity for a focus on Taihenjutsu increases. It is an inverse proportion. With greater focus on Taihenjutsu, one learns to stay in the safest possible position and thus reduce the probability of physical harm. It also causes opponents to expend more energy while revealing chinks in their armour that can be exploited. This further reduces the need for speed and strength even more (a virtuous cycle).

A key aspect of the martial arts as one learns from highly experienced masters and practitioners is to not try to fight the opponent. This is not to be construed as not doing anything. It is just a reiteration that Taihenjutsu is to be relied upon, until an opening is revealed. It is also a reiteration that Taihenjutsu saves you, even if it does not defeat the opponent.

This tenet of “not fighting” is usually also accompanied by “do not use strength or power”. It is essentially the same thing, focus on Taihenjutsu. But this is easier said than done. Taihenjutsu as stated earlier is about responding to the opponent, not reacting*. So, what does Taihenjutsu entail? And how can one “respond” to the opponent? And how do these two result in not fighting or not being strong? The answers to these above questions will lead us to the notion of Ahimsa we started this article with.

In order to not fight an opponent, one can either get away from the opponent, maybe by running away. Alternatively one can stay in the fight and purely survive the fight, while not doing anything to harm the opponent. The latter helps us explain things better and hence will be our focus going further in this article.

In order to stay out of harm’s way, one needs to move expertly and evade all of the attacks of an opponent. Once this can be done, the next step is to move to a position that causes the opponent a disadvantage. This disadvantage can be the opponent losing balance, getting tired, losing focus or accidentally getting injured or worse. Any of the four outcomes mentioned lead to the opponent eventually losing the fight. Thus, one will have achieved a favourable outcome (not necessarily winning) by letting the opponent defeat herself or himself. Taihenjutsu of course, can be embellished to let the opponent “strike oneself”, “trip oneself” or in any general manner “cause harm to oneself”. But this aspect is not necessary for the purposes of this article and will be left out.

Thus, as seen above, it is possible to achieve the upper hand purely with Taihenjutsu. There is another overarching statement that encompasses both “do not fight” and “do not harm the opponent”. This is, “do not do interfere with the opponent”. In other words, let the opponent do whatever she or he wants. You just stay safe and on the lookout for openings with Taihenjutsu. This statement can be reworded to “do not cause any trouble for the opponent” with the same essence as earlier. Thus, we have the definition of Ahimsa that we started with. But we have seen how it is achieved with Taihenjutsu.

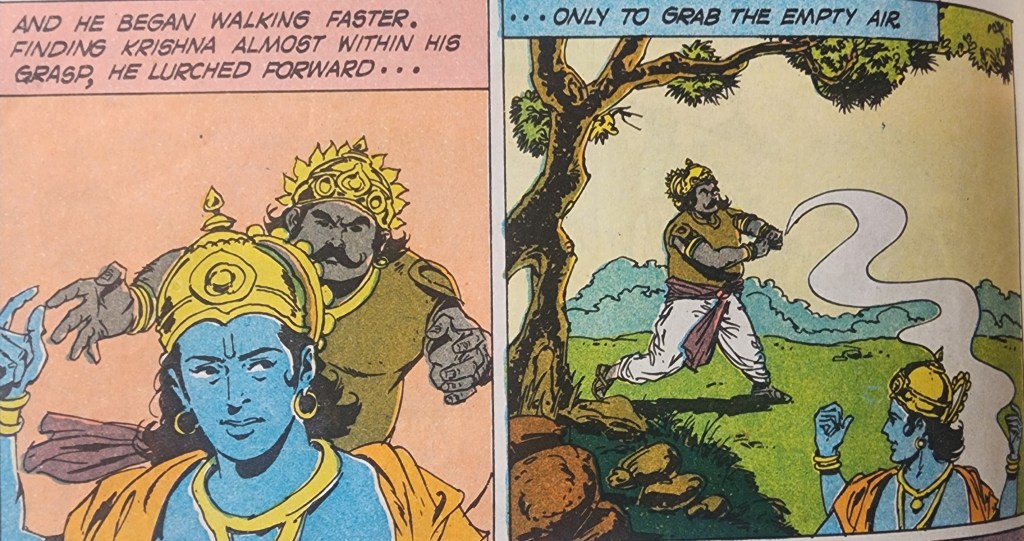

Krishna allowing Kaala Yavana put in all the effort, not getting in his opponent’s way, and yet leading him to his doom. Image credit – “Krishna and Jarasandha” published by Amar Chitra Katha.

The next question is, how does one achieve Taihenjutsu with Ahimsa? The answer lies in the fact that one should respond to an opponent and not react. With considerable experience in the martial arts one learns to “be aware of an opponent” or to be “mindful of one’s surroundings including the opponent” (this is Sakkijutsu in Japanese). This is not easy and requires many years of practice. But when one achieves the ability to be mindful at all times in a fight (preferably at all times in life). Once one is mindful of all of one’s surroundings, staying in the safest position in a dynamic situation even as an opponent is attacking is easier (never just “easy”), as there are in reality only a handful of actions open to any opponent at a given instant.

Once a martial arts practitioner can achieve mindfulness, it gradually becomes easier to read an opponent. Once an opponent can be read, his or her attacks can be responded to, sometimes even with accurate prescience. The need to react to an attack diminishes. Thus, an attack and a threat from an opponent can be nullified. This explains how to switch from reacting to being responsive. The next question that comes up is how does one achieve mindfulness and learn to be responsive and not just react. The answer to this can only truly be understood with experience and a lot of practice. It becomes evident as a revelation while training and not as a worded understanding. But an attempt will be made here to elucidate this in words.

To be mindful, the starting point is to not have a “mind that is full”. A mind is full, in the context of a fight, when one has an agenda or objective, specifically towards the opponent. This is especially true when one has a need to defeat an opponent and not “let the opponent stop being the opponent”. Also, generally, when one conceives of an opponent, the need to overcome an opponent has connotations with the EGO. One needs to achieve objectives in a fight to be satisfied with oneself, sometimes irrespective of the outcome of the fight itself.

The drive to achieve the ego driven and result oriented objective, especially with increasing time in a fight results in focusing on the objective rather than the actual reality of the opponent. This results in the mind being full and prevents mindfulness. This reduces the ability to read the opponent and thus potential opportunities in a fight. This also creates openings for an opponent to exploit. This last point leads to reactions instead of responses. Thus, there is no Taihenjutsu, only a fight.

Based on the above observation, the simple means to achieving mindfulness is to let go of all ego and individuality in a fight. Have no desire or emotion towards the opponent. Just accept the opponent, the space around (terrain) and all other factors. Have no complaints for the situation one is in, have no plan or desire for after the fight. Do not complain when the opponent seems successful in attacks. Accept hits and pain. Do not consider and worry about humiliation and reputations. When all of this is done, the mind is empty and capable of mindfulness. Control your mind to prevent these thoughts. In other words, achieve SELF CONTROL to achieve mindfulness. Self-control is the beginning of the path to efficient and effective Taihenjutsu. Self-control includes both mind and body, but generally begins with the mind as anyone who perseveres in any crisis knows.

We have now seen how Taihenjutsu leads to and is improved by Ahimsa. Also, the path to good Taihenjutsu, is self-control, starting with the control of the mind. Thus, Ahimsa is also a state of mind. One can be in a fight, which might result in a grievous and injurious outcome for the opponent, but that is not due to your intent to cause harm to the opponent. The bad outcome for the opponent is a consequence of his or her ill will which started the fight in the first place. Finally, this means that Ahimsa does not require one to suffer in a fight and definitely does not require one to shy away or run from a fight (except for survival, which is a tactical retreat). The notion of “turn the other cheek” is a fallacy with our understanding (It is only a good strategy in asymmetric warfare where one wants to shame the person slapping. But asymmetric warfare is beyond the scope of this article.).

In essence, “Ahimsa paramo dharmaha” only means that is always right not to have malicious intent towards anyone at any time, not because harming others is wrong, but because it maximizes the chances of the opponent causing harm to herself or himself. This way the chances of one starting a fight diminish considerably and the chances of effective conflict management increase exponentially. In conclusion, survival of life and life styles is of paramount importance and should never be held hostage to a false notion of non-violence, which has nothing to do with the concept of Ahimsa.

Notes:

This article is written with the example of a small one on one fight. But it applies to larger conflicts as well. All of the points above apply to any conflict management (conflict resolution is a bad joke) situation in all walks of life.

*- A reaction is thoughtless, mostly driven by conditioning (Jokin Hansha in Japanese). A response is based on the situation and mostly a “considered” action.

One can replace the word “mindfulness” with “awareness” if that makes one more comfortable reading this article. They are used in the exact same context here.

Very well written & extremely interesting perspective on Martial art & Ahmisa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/13/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-1/ Versión original en ingles. […]

LikeLike

[…] Seen below is the link to the article where I discuss my ideas about Ahimsa in greater detail. https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/13/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-1/ […]

LikeLike

[…] * https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/13/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-1/ […]

LikeLike