The Ashta Siddhi are regarded with great reverence in Hindu culture. “Ashta” means eight, “Siddhi” is an ability or skill, but could also be termed as a power. Siddhi is something that is achieved through Saadhana, which is thorough and sustained practice. Many of the great Gods and Goddesses from Hindu scripture and the epics are said to have achieved the Ashta Siddhi. These include various forms of the Devi, Ganesha, Krishna, and most popularly, Lord Hanuman had all mastered the Ashta Siddhi.

The Ashta Siddhi are as defined below.

- Anima – The ability to make one’s self very small

- Mahima – The ability to make one’s self very large

- Laghima – The ability to make one’s self very light

- Garima – The ability to make one’s self very heavy

- Praapti – The ability to get or obtain whatever one wants

- Praakaamya – The ability to acquire or achieve anything one wants

- Vashitva – The ability to control anything or everything

- Eeshitva – The ability to be superior to everything or attain Godhood

From a cursory look at the eight abilities mentioned above, it is easy to notice how they are related in pairs and complement each other.

- Anima and Mahima are related to the physical volume of the person with the ability.

- Laghima and Garima are related to the physical mass of the person with the ability.

- Praapti and Praakaamya go hand in hand since one has to be able to acquire to obtain something and one should be able to receive something that is acquired.

- Vashitva and Eeshitva are related because to be able to control everything is to be a God, and to be a God requires the ability to control everything.

Another aspect to consider with relation to the Ashta Siddhi is the fact that these abilities are associated with the Gods in Hindu culture. This generally suggests two things. One is that these abilities are not attainable by normal mortal humans. The second is that these are fantastical and since they are associated with religion and the Gods, they are all fantasy. Both of these are valid.

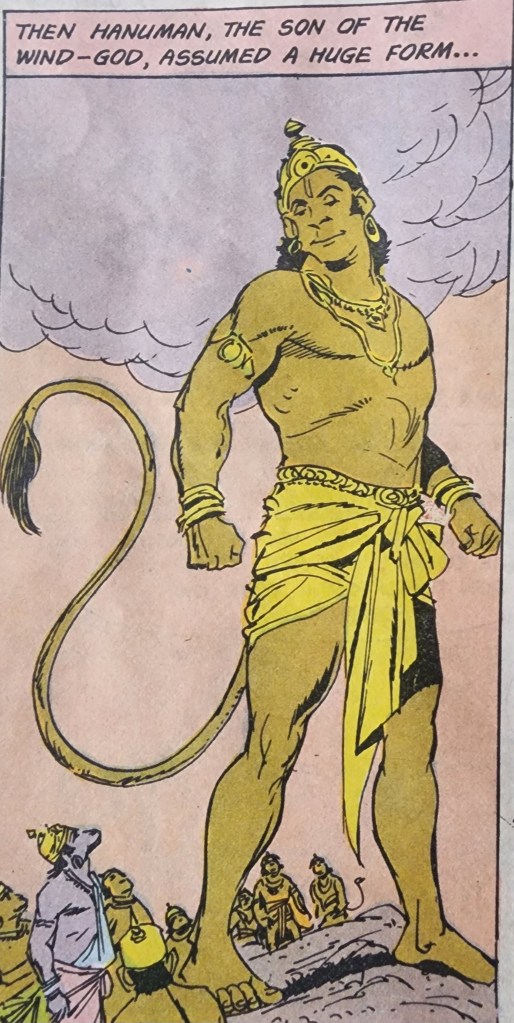

Some of the definitions used for Anima mention that it is the ability to shrink one’s self to atomic sizes and the Mahima is to be able to expand one’s self infinitely. An example of Anima is when Hanuman shrank himself to the size of a fly when he slew Mahiravana to save Rama and Lakshmana from being sacrificed. Similarly an example of Mahima is when Hanuman expanded his size to be able to lift a mountain to save Laskhmana during the war in Lanka. This definitely is beyond what normal humans can ever do.

Similarly, one of the definitions of Laghima is to be able to make oneself as light as air! Praapti and Praakaamya by definition seem magical. How can one obtain anything one wants or acquire anything one wants! All normal humans have limitations and constraints. The last two abilities again, by definition are to achieve divinity and thus, are beyond normal humans.

Of course, there are people who do say that these are abilities that can be and are achieved through prolonged and intense yoga and yogic practices. I am not aware of anyone who has ever been able to demonstrate these abilities as defined in the absolute superhuman sense. If there are people with such abilities, they have kept themselves from the public eye.

With this introduction, I would like to look at a few concepts from Budo and the martial arts which explain the eight abilities in a more mundane manner. These concepts are analogous to the Ashta Siddhi, but only as they would be used in a fight between humans or in a situation needing conflict management among normal humans.

Fair warning, these concepts from Budo are very simple in some cases and relevant only in a fight, not even remotely are they magical, but are certainly based on common sense. Also, the analogues from Budo might not pair up as neatly as the original eight, nor would they be as neatly flowing from one to the other like the original eight. They just go to show that the same (or at least similar) concepts exist in both cases, while one is preserved with magical stories, the other through living martial art forms that have a long history and lineage. Perhaps the use of stories is what allowed the Ashta Siddhi to be so neatly flowing from one to another? One can only speculate.

Anima and Garima

The concept of Anima and Garima go hand in hand in reality. When one lowers her or his core (essentially one’s centre of gravity), the person feels heavier to anyone trying to dislodge them from that specific posture. This is true in all martial arts and sports and it is common sense for all humans. This is also at the root of all kamae, or physical posture in the basics of Budo.

What one has done in lowering her or his core is most likely widen one’s stance, by increasing the distance one’s feet and bent the knees, thus also reducing the height. So, the “size” of the person has reduced in one of the 3 axes (consider it the Z axis) while also seemingly increased the weight with the same mass. So, in effect, one has become smaller and heavier at the same time.

Thus, these two are really easy to understand. If a martial artist trains her or his core and leg strength and the ability to move her or his feet easily irrespective of physical size, both Anima and Garima are achieved. The speed of movement of the legs also depends on the martial artist not resting on the heels and instead learning to use the ball of the feet and the toes to hold their weight.

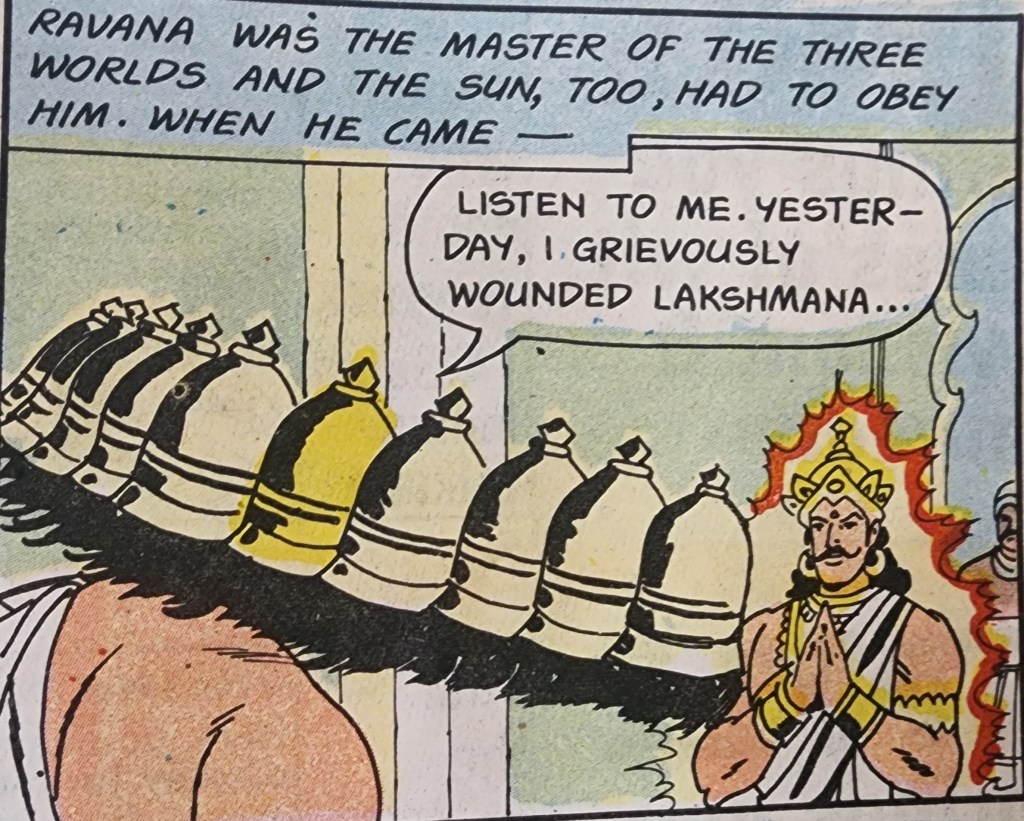

Image credit – “The Ramayana” published by Amar Chitra Katha

Of course, reducing one’s size also includes being able to go down on the knees, falling and getting up, sitting down and getting up as well. It also includes being able to change the angle of one’s self in relation to the attacker. For example, turning one’s side to the attacker exposes a far smaller surface area open to the attack (this is making one’s self smaller in either the X or Y axes). This is like a primary tenet of the “Totoku Hyoshi no Kamae” (the posture to protect oneself by making oneself as small as possible to use whatever one’s weapon is, as a shield).

There are a few other concepts that come to mind as going hand in hand with the Siddhis of Anima and Garima. One relating to Garima is the concept of Fudo, which translates to “Immovable”. To be immovable one needs to be of great mass, or more realistically, be able to manoeuvre one’s size and weight as required by the situation to prevent one’s footing or balance from being taken by the opponent. Here, I am not considering the use of Fudo in relation to one’s spirit or attitude.

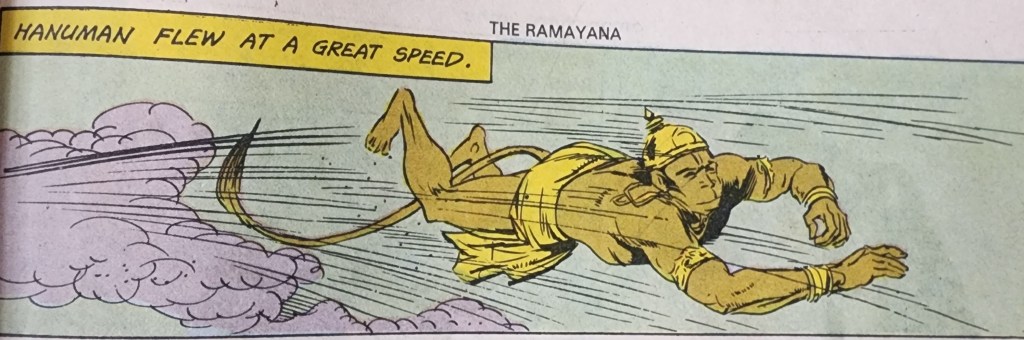

Image credit – “The Ramayana” published by Amar Chitra Katha

In the Bujinkan, we study the Gyokko Ryu. The origin of this school is supposedly by a Chinese princess and was to be applied by a small person for defence in the somewhat smaller confines of an indoor setting. Complementing this, the theme of the year for the year 2015 in the Bujinkan, was “Goshinjutsu”. This translates as “self-protection” (NOT self-defence). One of the things taught as part of this theme was to be able to protect one’s self while not being big and strong. Soke Hatsumi Masaaki emphasized that all practitioners should learn to move and fight like women; he meant that one should learn to be able move and fight like a generally smaller and less strong person against any size of opponent. This concept holds true irrespective of whether one is a man or a woman, young or old. The Gyokko Ryu, by virtue of its origins emphasizes that one should be able to keep one’s size small and heavy (when necessary). This is to not only present a smaller target (bundle of opportunities) to the opponent, but also to not be constrained by one’s size in any space (a large person might not be able to move freely indoors). This also means that any attack on an opponent will require generating power with a shorter strike range.

Mahima and Laghima

Mahima and Laghima, as a converse of Anima and Garima, go hand in hand, though not exactly. While lowering one’s core or centre of gravity increases stability, this is detrimental to quick movement. Stability generates an inertia against movement and so adds a little extra effort to move. This is great for training though, and with time, it might be mitigated to quite an extent.

But then, one needs to understand Mahima not as an opposite of Anima, but as a transformation of the body. If one needs to perform a roll, a human being has to reduce her or his size in the vertical direction or Z axis and increase size in the horizontal direction, at the beginning of and during the roll, depending on how far the roll needs to be. So, in a real scenario where there is no magic and no spontaneous shrinking or expanding happens at a cellular level, Mahima and Anima are complementing each other, where a reduction is size in one axis results in an increase in another.

Laghima on the other hand is not really about a change in the size or shape or even posture, but more about control of one’s own body. This again relates to the extent of, duration of and quality of training a martial artist has put in. The ability to use the toes and ball of the feet as against the heels, the strength in the core and control of the same, ability to move the entire body as one, control of the facea, all of these play a role in the ability of the martial artist to achieve Laghima in her or his movements.

One of the definitions of Laghima is to be very light and be able to float, like on air***. In Budo, there is a concept called Ishito Bashi. This refers to the stones skipping on water. This concept captures the essence of Laghima very well. Stones being heavier than water should skink, but then, when they strike the surface at a specific angle and velocity, they can and do bounce off the surface multiple times. This does not mean the skipping stone is lighter than water, but can surely behave that way under the right circumstances. In this same manner, a martial artist is taught to be able to be extremely responsive to an attacker’s movements, and even intentions.

Image credit – “The Ramayana” published by Amar Chitra Katha

This concept means a martial artist (Budoka) should not be stiff in the body and fixated in her or his intended movements. But instead, should be able to respond to the opponent (not just react). This requires being light on the feet and flexible in the body and mind. This also leads to additional concepts like “listening with the whole body” and training one’s intuitive abilities in a conflict management scenario. In other words by not being tied down by a stiff body and preconceived notions in the mind, one is extremely light and able to respond almost instantaneously to an opponent, making it seem like one is impossible to hit or respond to, for the opponent gets no feedback at all to form an attack. To put it in a poetic manner, a Budoka can, with lots of good training, “float on the intentions of the opponent”, just as a stone can skip on water. This is just a practical application to someone saying you should be light as the air and impossible to either catch or hit.

Having considered the concept of rendering oneself incapable of being attacked by being light, it must be understood that the same can be achieved through armour. This is using technology to augment physical abilities or making up for the lack of the same, or both in some cases. Armour protects the body and can allow one to get away with not being able to be light and move very efficiently. But armour also makes one heavier, and also larger. Think of all the body armour used in the past; samurai armour, full plate harness, or even modern day body armour. All of these make a person larger (in volume). Add a helmet to this and even the height is increased. Overall, a person appears more substantial in armour.

In the Bujinkan, we train the Kukishinden Ryu, a martial school which traditionally used armour. The use of the same necessitates a physical posture with any weapon to be larger than one when not using armour. For this reason, there is even a kamae (physical posture) called “Daijodan no kamae” which translates to “large high level posture”, the key here being the prefix “Dai” (large).

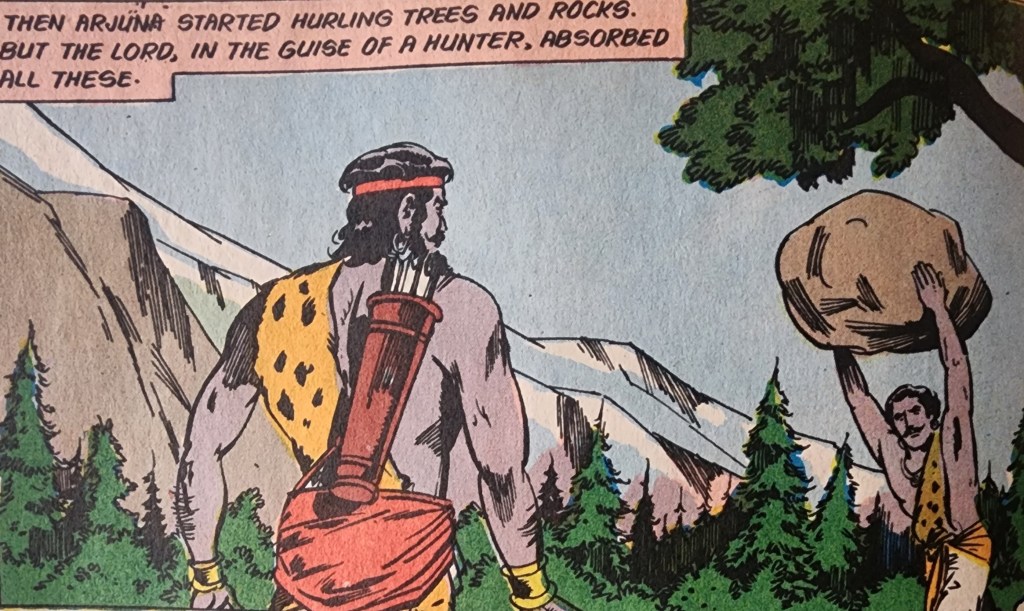

Image credit – “Mahabharata 20 – Arjuna’s Quest for Weapons” published by Amar Chitra Katha

This also shows how being large, or using Mahima, can also refer to just occupying greater space, like in armour. Hence, adding a weapon to the mix also achieves the same. This seems pretty similar to a country being considered powerful in the modern sense if it has the ability to strike far from its shores due to standoff range weapons and long range missiles. Or possess the ability to cripple other nations with armies of hackers in the cyberspace. The country can be small, but the “space” it controls (exercise influence over), geographical or cyber is “large”.

Praapti

The word “Praapti” and its forms are still used pretty often, compared to the terms for the other seven Siddhis. In Kannada for example, it could be “Avanige yenu praapta aayithu?” or “What did he get?” and in Hindi an example could be “Tumne kya praapt kiya?” or “What did you obtain?” As seen in these two examples, in common parlance “Praapti” means “get” or “obtain”. In either case, it boils down to “receiving” something.

The concept of “receiving” is literally the foundation of both the basics and advanced stages of the martial arts in the Bujinkan system. Ukemi and Uke Nagashi are the first things taught in the basics of the Bujinkan. Ukemi refers to “receiving the ground” and hence involves rolls and break falls. It has everything to do with how to injure oneself the least when one has to fall. Uke Nagashi refers to “receiving the uke (opponent)”. This deals with the different ways one can absorb, block, counter, deflect or evade an attack whether the attack is from a higher, lower or any other angle. So, literally, how one can obtain safety while being attacked or falling is the crux of this “receiving” and reiterates how one should be able to have “praapti” of safety.

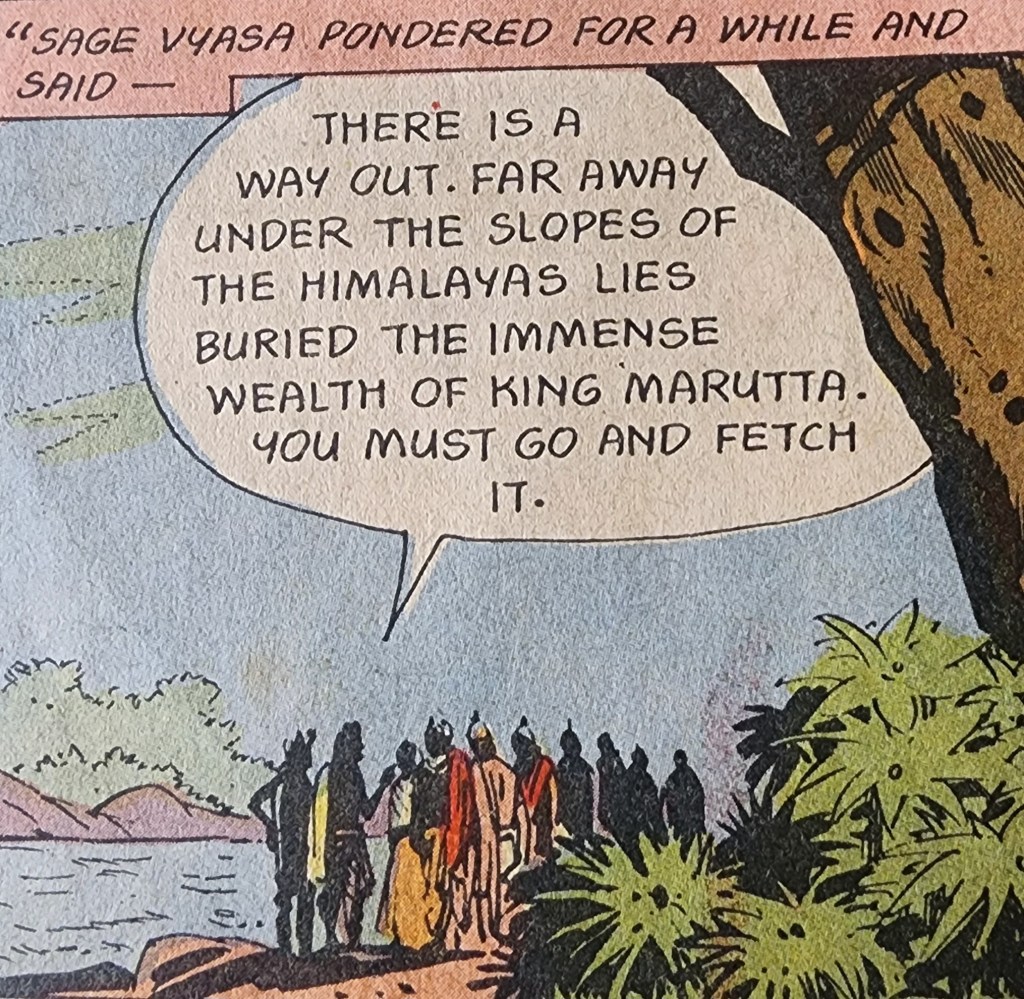

Image credit – “Mahabharata 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna” published by Amar Chitra Katha

At a more advanced level, as Nagato Sensei (One of the senior most teachers in the Bujinkan) says, everything begins with Sakkijutsu. Sakkijutsu is about developing the intuitive ability in a fight (or any conflict management situation in daily life) to be able to move pre-emptively to either cause the opponent(s) to be in a disadvantageous position or to put one’s self in the safest or most advantageous position in relation to the opponent.

In order to be able to use intuition to one’s advantage, there are two things that are needed. First, one must have a lot of experience in training, of trusting one’s intuition and facing the consequences of failing to do so. The second relates to what we discussed with respect to Laghima, to be able to listen to the opponent and her or his surroundings to be able to intuit their intention and moves. The first of these two is about receiving knowledge and experience (Gyan aur anubhav “praapt” karo – in Hindi). The second is about receiving information from the opponent and surroundings, even when it is not explicit. Here, Praapti is all about obtaining the ability to survive, through safety and perhaps success. This is something everyone does at all times in life. We use experience to be great in any field and usually this is because we can read the situation and be in the right place at the right time. Perhaps this is a precursor to being lucky.

Praakaamya

This is the Siddhi that, from my perspective, belies any direct correlation with a concept in Budo. Praakaamya means the ability to acquire anything. Because this article is in English, there is one question that would surely come up. What is the difference between “obtain” and “acquire”? The general understanding would be that “acquire” implies more effort on the part of the person who gets something, as against “obtain” which could be either effort or any other means, like finding, being gifted and such. This is why I have understood “Praapti” to mean “receive” more than to “obtain”. So, by my interpretation, while “Praapti” is to receive, “Praakaamya” is to be able to take. So, with respect to “Praapti”, the person receiving is, to an extent passive, while with “Praakaamya” the person taking is, to an extent, active. Also, like Praapti, Praakaamya also relates to life in general, not specifically to a fight.

With this basic detail about Praakaamya Siddhi, let us look at some concepts from conflict management, war strategies and a situation where individuals are fighting. In any conflict, if one has all the information about the abilities, numbers and position of an opponent(s), and also knows everything about one’s own strengths, skills, numbers and positions, the opponent can always be overcome. This is true if the same information is not available to the opponent.

In Budo, we learn two concepts, one called “Yoyu” and another called “Kurai Dori”. Yoyu refers to having a surplus of everything. Kurai Dori refers to strategic positioning. If one has a surplus of information, experience and skill, once can always achieve a favourable strategic position against an opponent, and cause the opponent to be in a disadvantageous situation or maybe defeated. Also, if one is able to achieve favourable a strategic position, gathering surplus information might become easier. These two are thus, complementary.

Image credit – “Mahabharata 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna” published by Amar Chitra Katha

With the Siddhi of Praapti, one has all the skills, experience and also all the information about the opponent. With the trained intuitive** abilities, if the opponent knows or plans somethings (or even thinks it!), so does the one defending. So, with Praapti achieved, one has everything needed to always achieve a successful strategic position against an opponent. Thus, Kurai Dori is a variant of Praakaaamya in a conflict. If one can “acquire” a strategic position, once can acquire a surplus of everything, including information, so “Yoyu” is achieved. With these two concepts applied in practice, anything can be achieved, and thus anything can be acquired. In this way “Praapti” and “Praakaamya” form a virtuous cycle, as do “Yoyu” and “Kurai Dori” Thus, “Yoyu” and “Kurai Dori” are a fair approximation of Praakaamya. Of course, this needs a foundation in Praapti, represented by Sakkijutsu, Ukemi, Uke Nagashi and other layers of training.

Vashitva

Before delving into Vasitva and its antecedents in Budo, I need to clarify something here. As I have been writing this article, I realize that I have to clarify the progression of the eight Siddhis. They are not acquired linearly. It is at best circular. The eight Siddhis complement and enable each other. It is not like eight different weapons being acquired. It is more akin to having a weapons platform, like a fighter aircraft, whose sensor package, weapons array and engine behaviour are variable and mission specific. The airframe with its stealth abilities is like one of the Siddhis, while what this platform carries are the rest.

The above point was important as we discuss the last two Siddhis. I have seen some mention Vashitva first, and some others mention Eeshitva. Personally, I feel Vashitva should be before Eeshitva for reasons I hope will be clear in a bit.

In Indian vernacular languages, “Vashikarana” means to be able to hypnotize and thus control someone. “Vasha” means control. Thus “Vashitva” means “to be able to control”. So, the seventh Siddhi is to be able to control an opponent(s) or just about anything on the planet, like plants, birds, insects and animals. When speaking of control, it is vital to mention that one should not let oneself be controlled and also ensure the following two. One should not let on that he or she is not being controlled and if possible, also make the opponent believe that they are in control.

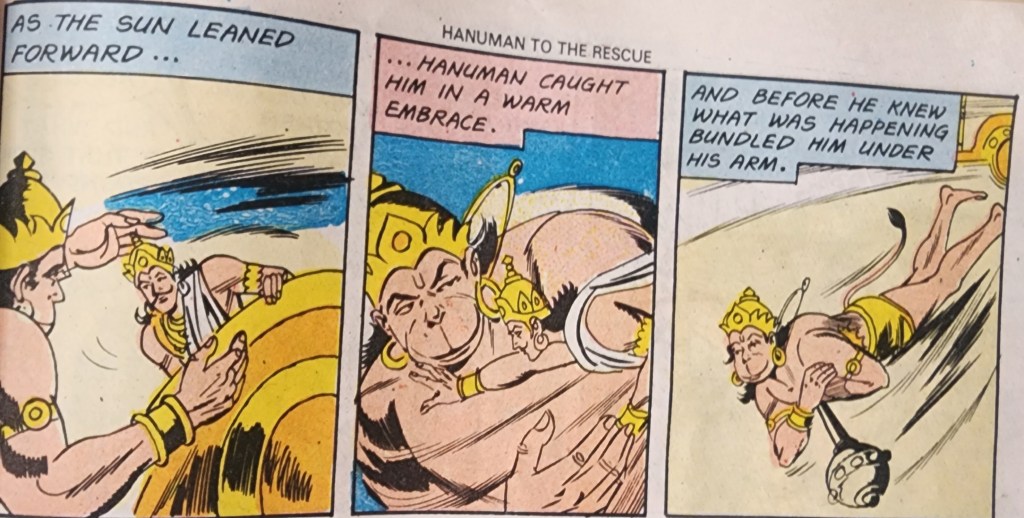

Image credit – “Hanuman to the Rescue – Tales of Hanuman” published by Amar Chitra Katha

In the Bujinkan, there is a trinity of concepts, “Toatejutsu”, “Shinenjutsu” and “Fudo Kana Shibari”. “Toatejutsu” refers to “striking from a distance”, “Shinenjutsu” refers to “capturing the soul/spirit of the opponent” and “Fudo Kana Shibari” refers to “an unshakable iron grip”. The three used together refers to “Striking from a distance to capture the soul/spirit of the opponent in an unshakable iron grip”. The soul or spirit here refers to the fighting spirit or the will to fight of the opponent(s). If this is achieved, Vashitva is as well.

The path to achieving the three concepts mentioned above and therefore Vashitva, is found in some of the themes of the year in the Bujinkan in the past 20 years. The themes I am referring to are, “Kasumi no Ho”, “Kuki Taisho” and “Menkyo kaiden”. “Kasumi no ho” refers to the “way of fog”, “Kuki taisho” refers to “the smile of the ninth demon” and Menkyo Kaiden refers to “confusing the opponent with conflicting signals”.

“Kasumi no ho” means moving in a way that causes confusion to the opponent, and hence affects either the will to fight of the opponent or causes the opponent’s plan of action and therefore the intent to falter due to induced self-doubt. “Kuki taisho” is about being so confident in one’s own ability and exuding menace without any action. This is an attitude to cultivate in oneself. This attitude is supposed to actively deter a fight or conflict from occurring because the opponent’s will to fight wilts before the fight ever begins. “Menkyo kaiden” is about messing with the opponent’s mind. This is roughly “kasumi no ho” with the will of the opponent (Kasumi no ho itself was related to physical movement). It can also be called “kuki taisho” applied repeatedly at varying intervals for varying durations. Of course, all these are layers added on top of one another, first achieve the physical and add the intellectual and emotional aspects to embellish the physical. As must be obvious by the objective of these three concepts, they lead to controlling the opponent’s will and his or her means to fight (this includes the plan of action). This is “Vashitva” 101.

I have to add here, specifically in relation to the Bujinkan system. The focus on “control” has been paramount since Hatsumi Sensei started his focus on Muto Dori from around 2018. Everything he has been teaching focuses on control. First, try to achieve complete control on oneself and then this will likely lead to control of the opponent(s). Of course, this is a wonderful concept, but frightfully hard to achieve, even just the first part about self-control. So, achievement of “Vashitva” is literally what Soke has been driving towards over the last few years.

I have one last point to consider with regard to “Vashitva”. If one can control one’s shape and size, weight and volume through the achievement of Anima, Mahima, Laghima and Garima, the first four Siddhis, one should be able to go anywhere and reach anywhere (specifically in the context of the martial arts or a fight, but in general as well). Then, that person should be able to obtain or receive anything and hence acquire anything. If one can have anything that is needed at will at and all times, through the achievement of the Siddhis of Praapti and Praakaamya, one has already achieved self-control and hence should be able to control everything and all opponents, thus achieving Vashitva. If one can control everything, then one can continue to obtain and acquire anything and thus perpetuate the ability to control one’s own mass and volume (it just means that newer means to achieve the first four Siddhis can always be discovered). This is what I was referring to when I suggested that the Siddhis are more circular rather than linear. They feed off and add to each other, completing the virtuous cycle. And this leads us to the eighth Siddhi.

Eeshitva

I have seen the meaning of this Siddhi as “the ability to force or influence anyone” or “absolute superiority” and even “the ability to restore life to the dead”. Personally, I feel all of these are underwhelming. Of course, if one can control everyone and everything, that person can indeed force or influence those under control. This is obviously absolute superiority. I will refer to the restoring of life later in this section. Also, I use the spelling as Eeshitva and not Ishitva like in many sources, as I feel that is more accurate in comparison with the spelling in vernacular Indian languages.

Eesha is another word for God. It is very similar to the word Eeshwara. Eeshwara could specifically refer to Lord Shiva or generally mean God. Eesha is also the Guardian of the North-Eastern direction. So, however it is seen, Eesha refers to God. So, Eeshitva is about achieving the ability to be like God, be it in a fight or conflict or any situation in general. In other words, to be able to lord over all problems, if not simply, everything.

The definition of Eeshitva makes it clear that it will always be a work in progress for all humans. No mortal can become a God for there is no definition of Godhood. I cannot think of any examples for Eeshitva from either daily life or the martial arts/sports worlds. Of course, one can think of martial artists like Miyamoto Musashi who never lost a duel, or Venus Williams at her peak or Dhirubhai Ambani when he grew his company with seemingly no end, to have achieved Eeshitva for a time in a given context. But this is very similar to achieving Vashitva where the aforementioned people could control all variables in a duel or on a tennis court or in the business ecosystem, for they definitely seemed to be in complete control of their respective environments. But none of them could be Godlike since they were all specialists in their respective fields, as are most people on Earth. No human can claim control on everything and hence Godhood.

The above clearly shows how Vashitva in all areas, automatically leads to Eeshitva. This is why I had mentioned earlier that I prefer to place Eeshitva as the eight Siddhi, after Vashitva, as this is a stepping stone to being Godlike.

Even though no human can likely achieve Godhood, I would to refer to concepts from Budo, which show that the pursuit of improvement and accepting natural principles are universal and guide one to at least be able to be a conduit to divine inspiration and action, even if not actual Gods.

In Budo there is a concept called “Kami Waza”. This means the technique of the Gods. It refers to moving a fight in a way that seems like one is being guided by or moved by the Gods themselves. You could say, the person who seems Godlike, has let the Gods let her or himself be controlled by the Gods. By removing oneself from the situation, space has been made in their body, mind and spirit to allow the Gods to be in control. This is to cause the opponents to no longer be able to be an opponent. The choice of words here are deliberate, I am saying the opponent no longer being able to be one, not that the opponent is defeated, hurt or affected by any malicious intent. So, for normal humans allowing for a space where Godlike movement can be achieved, that is Eeshitva on a small scale in a given context.

Image credit – “Hanuman to the Rescue – Tales of Hanuman” published by Amar Chitra Katha

Here is where I would to refer to defining Eeshitva as being able to bring people back from the dead. In reality, for humans, this is similar to protecting people from death. If one can end a conflict with the least harm to people and minimal or no loss of life, with the help of Gods if necessary, this is close to being Godlike. Weapons of deterrence in the modern world could arguably, in a twisted way, be an example of this. If one is extremely good in the context of a fight and the opponent cedes without fighting, it is a step towards Eeshitva.

In the Bujinkan, like with Vashitva, there were a couple of themes studied a few years ago that could be stepping stones towards Kami waza, or Eeshitva. One is “Jin ryu kaname omamuru” and the other is “Shingin budo”. “Jin ryu kaname omamuru” refers to being able to see the essence with the eyes of the Gods. It means being able to perceive the crux of anything almost instantly, like the Gods can. “Shingin budo” refers to moving in a martial way while being guided by the brilliant artistry of the Gods. This means one’s martial movement seems to be awesome like that of the Gods or at least like one is guided by them.

Both of the above emphasize that one can be Godlike only by allowing the Gods to either control them or more appropriately by one allowing oneself to be a conduit for the Gods. This means that one’s perception is so on the dot or martial movement is that incredibly good, that it seems they are a vessel for the Gods. This begs the question how does one allow oneself to be a conduit for the Gods?

The Bujinkan system, time and again has emphasized that advanced practitioners should learn to unlearn, and strive to achieve self-control to control Uke (opponent). This means one should not be fixated on techniques and how they are done and should learn to adapt the same to the scenario. There is no need to be traditional and one should not celebrate a collection of techniques for their own sake. These should be a guide to natural movement. Natural movement just means doing the best thing that can be done in a given situation. This in turn means, one should be able to let go of intentions, plans, ego and emotions relating to a given scenario. This allows “Natural movement”. And when one is fully able to move naturally, one can hopefully find the best solutions at great speed, and this is akin to being guided by the Gods.

An example from Indian culture for letting go of oneself is how Lord Krishna does the only thing that is possible in his wars against Jarasandha. He did not fear disrepute when he ran away from the battlefield against Kaala Yavana, who in turn followed him to his death in a cave (this is a story beyond this article). He also decided to move his entire city state far away from Jarasandha’s neighbourhood and eventually Jarasandha was also slain off the battlefield. Using his ego against him was a big part of this, but again, this story is beyond the scope of this article.

Of course, just because the concepts exist, does not mean the path does. These concepts are difficult to practice to the point of impossibility, let alone achieve. And that brings me to end of this long winded look at the connections, from a personal perspective, between the classical Ashta Siddhi from Hindu culture and the concepts of Budo, specifically the Bujinkan system of martial arts.

Notes:

1. I sometimes use Bujinkan and Budo interchangeably. It is not really correct. But it is pretty representative. Apologies for this and a big thanks to my readers for bearing with me on this.

2. **Intuitive abilities are pretty synonymous with “mindfulness”

3. *** An example of this would be when Hanuman flew across the sea to Lanka and then to the Himalayas and back. Of course, this is an example of a God displaying a fantastic act, and not something that can ever be expected of humans.

4. I cannot think of any direct examples from stories in Hindu culture for Praapti and Praakaamya, without some personal interpretation being added. Praapti could be when Hanuman received the revelation of his forgotten powers from Jambawan exactly when he needed to be able to cross the sea to Lanka. Another example of Praapti that comes to mind is, when Yudishtira was distraught at not having starting capital for performing the Ashwamedha Yajna after the Kurukshetra war, Sage Veda Vyasa easily solved his problem by revealing the location of buried treasure that could pay for the entire enterprise. Thus, in both cases, Hanuman and Yudishtira had put themselves in a position where they could “receive” (obtain) exactly the solution they needed at the exact time when they needed it.

5. An example of Vashitva that comes to mind is that of Ravana. His capabilities were such that he could order the Sun around! When Hanuman was on his mission to bring the Sanjeevini plant to heal Lakshmana before the morning of the next day, Ravana ordered the Sun to rise earlier! Presumably to cause the temperature change to kill Lakshmana. This is control on a GRAND scale! But then, Hanuman, imprisoned the Sun temporarily to foil that! That is Eeshtiva, if ever there was an example of one.