Early in the Mahabharata, there is an incident that occurs at the ashrama of Guru Dronacharya. He sets up a test for all his students, essentially all the Kuru princes. He has a model of a bird set up on a tree and tests the ability of the students to shoot an arrow at the eye of the bird.

To even be eligible to shoot the arrow, he asks them a set of questions to check their focus on the target. He asks each student what they see, when they have nocked an arrow and drawn the bow. He is checking if they see anything other than the eye of the bird or at least, just the bird. If they say that they see anything else, he tells them that they cannot strike the target and should withdraw.

Eventually of course, only Arjuna succeeds in the test. But what is important here is the response from Yudishtira. He can see everything even while trying to shoot the target, from the bird to the tree, its nest, the leaves and the insects on the tree (the entire ecosystem on the tree) and how he needs to be aware of all that he sees while shooting the arrow, as the action could lead to repercussions that affect these. Guru Drona, while telling him that he will not be able to strike the target with the arrow, is mighty impressed with how complete his vision is, at how he can see everything, in other words, the big picture. This was Yudishtira’s primary ability.

I am not sure if Drona being impressed with Yudishtira seeing everything is part of the original Vyasa Mahabharata or any other version. I have seen this on the Star Plus version of the Mahabharata. I am not sure if they made this up for the series or if it is taken from any original source material either. But the observations of a young Yudishtira is not a fake in any case and suffices for the purposes of this article. The link to the episode where the described event takes place is seen in the notes below1.

Yudishtira was raised to be a king, as was Duryodhana, simply because they were the oldest kids of their respective fathers. The ability to see every aspect of any situation and thus to gauge the ecosystem, is a fantastic ability for a king, who needs to be able to provide prosperity generating administration to a kingdom, and to see through the reasoning and motivations behind the suggestions of the high council (samiti).

Now, a primary difference between Yudishtira and Duryodhana is that the former is always known for his adherence to Dharma (hence the epithet Dharmaraja or Dharmaraya, raya & raja being synonyms) while is the latter is primarily a great warrior, one of the greatest ever.

The thing with Dharma is that it is not an objective quantity. It is a highly subjective thing. It can be broadly defined, at least with respect to a king, as doing that which is right for the kingdom, or society in general. And this “doing right” has to be towards upholding the natural order that permits life to survive and prosper. This includes rights, duties, laws, righteous conduct and so on.

Here, Yudishtira has what is quite literally, a superpower. From his ability to see everything even when he has to focus on the bird’s eye, it is clear that he always can look at the whole picture. Add to this, his yearning, perhaps due to his upbringing, to achieve the ideals of Dharma with every decision he makes, he really is perfectly suited to be a king.

From the Mahabharata itself, we see several instances where Yudishtira reaches out to other learned people when has a query regarding his actions and morals and their adherence to Dharma. This makes him additionally suited to kingship, because he is open to suggestions when a course of action is not really clear, a hallmark of someone who is not a tyrant.

At the same time, Yudishtira never absolved himself from the consequences of his decisions, because he was the one who always took responsibility for it, irrespective of who suggested the course of action, and how justified the ends were. This is demonstrated from his visit to Bheeshma to ask how to fell him and the lie he uttered to kill Drona during the war.

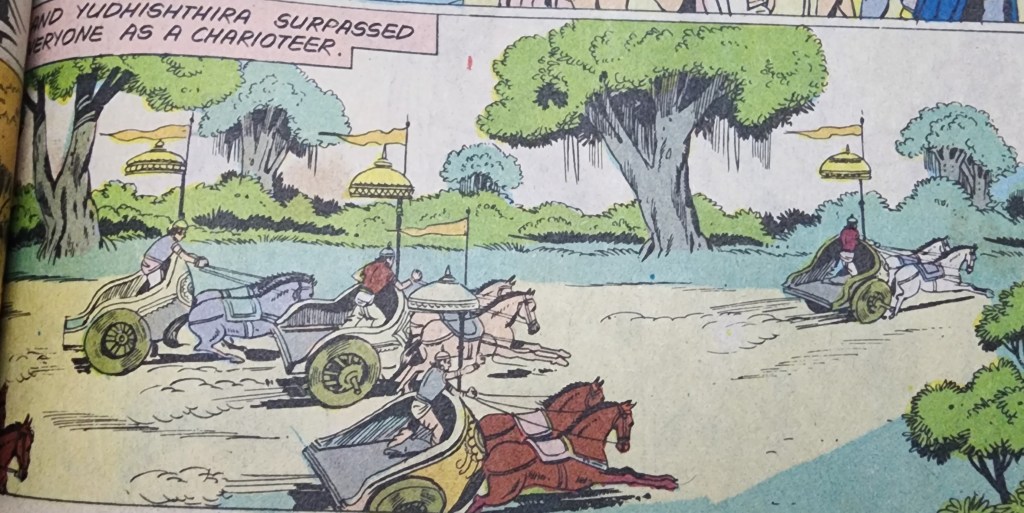

Yudishtira was the best charioteer among the Kuru princes. He was also the best spearman, and perhaps a good player of dice (what we call pagade in the vernacular). All three of these provide more evidence to his ability to be “mindful” and grasp all information about a situation, completely. Observe each of these 3 traits individually.

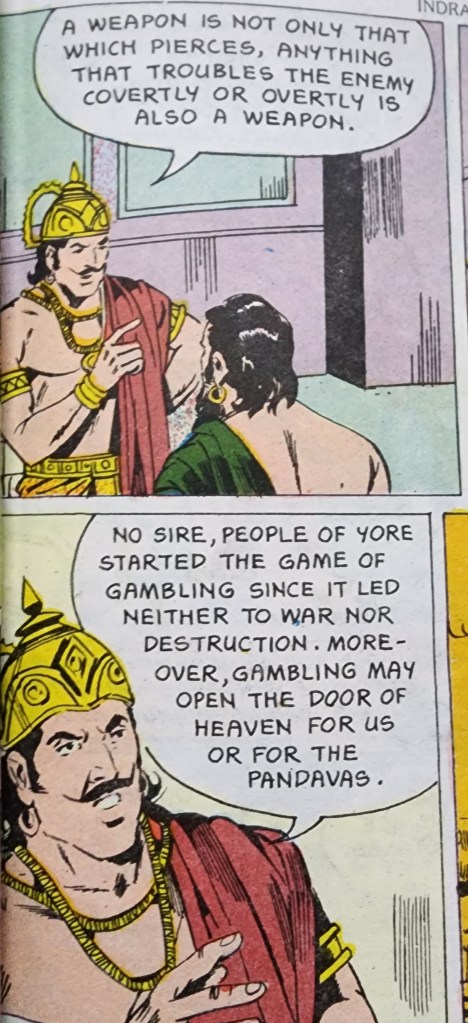

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 5 – Enter Drona

A good charioteer has to be able to navigate the terrain, his vehicle and the horses; an ability to be aware of one’s environment. A spear is a long range weapon, whether used in a formation of soldiers or individually. In both cases, the wielder needs to be aware of one’s surroundings. To use the weapon effectively, awareness is needed of one’s fellow troops so as not to hurt them and of the space available to effectively use the long weapon. Similarly, with a chariot, the comfort and safety (especially in a war) of the person in the chariot is something a charioteer needs to be mindful of apart from the other things. This is perhaps why great charioteers are remembered by name (Daruka, Shalya, Matali etc.)

Lastly, consider the game of dice, or pagade. This is not unlike a game of cards. You have no control over the value thrown up by the dice. But you use what is given to do the best you can to try and win the game. In other words, you need to be a fine tactician which hopefully translates to strategy when a king does the same with a kingdom. The fact that these games involve gambling does not take away from the skills needed to succeed.

Yudishtira’s skill with the chariot is not really known because there are other great charioteers in the epic, the greatest being Krishna himself. Plus, he was a king and perhaps did not drive chariots around at much himself. His ability with the spear however, is pretty well known.

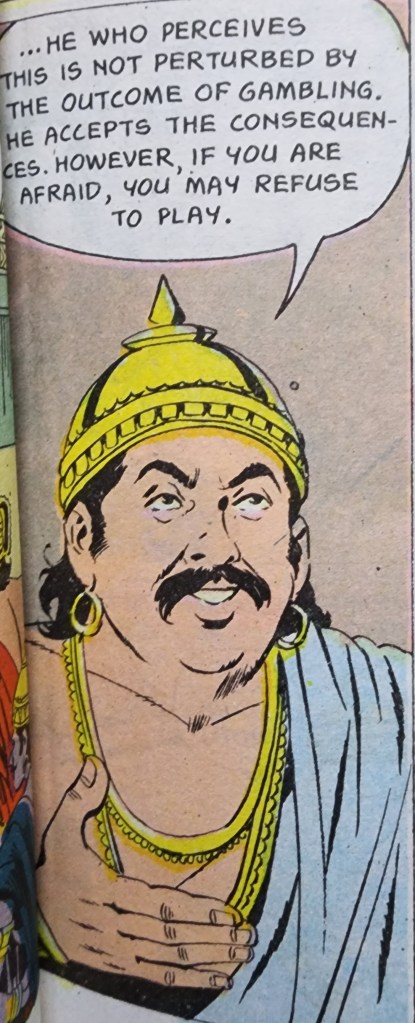

Yudishtira’s skill with the dice is a tricky one. His loss twice to Shakuni surely suggests he was not very good at it, and Shakuni even says that he is not very good at it. But there is information contrary to this. During the 13th year of their exile, when they are to remain hidden from the Kauravas, Yudishtira hides in the court of King Virata of the Matsya kingdom. He takes the identity of a Brahmin named Kanka. The interesting part of this is that he joins Virata’s court as someone who can instruct Virata in the game of dice! He does indeed instruct Virata and is never caught as someone who is poor at it. Does this not mean that he was good at pagade, but just not as good as Shakuni? Or was everyone else at Virata’s court so bad at pagade that they never realized Yudishtira was bad at it as well? Considering that Kshatriyas did indulge in dice, this may perhaps not be the case. Shakini taunts Yudishtira asking him if he is scared to play during their original match. Could this taunt be effective if it was not expected that a Kshatriya participate in dice without any worry? Is it not likely that this was even uttered only because all Kshatriyas used to play pagade often? I opine this is the case. Yudishtira just came up against the greatest player of that age in Shakuni and hence lost. Hence, just as he was upstaged by Krishna as a charioteer, he was no match for Shakuni at dice and hence is considered a bad player, even if he was in fact a good one. Also, perhaps Shakuni had supernatural advantages, or was very good at cheating and getting away with it (maybe he used loaded dice?).

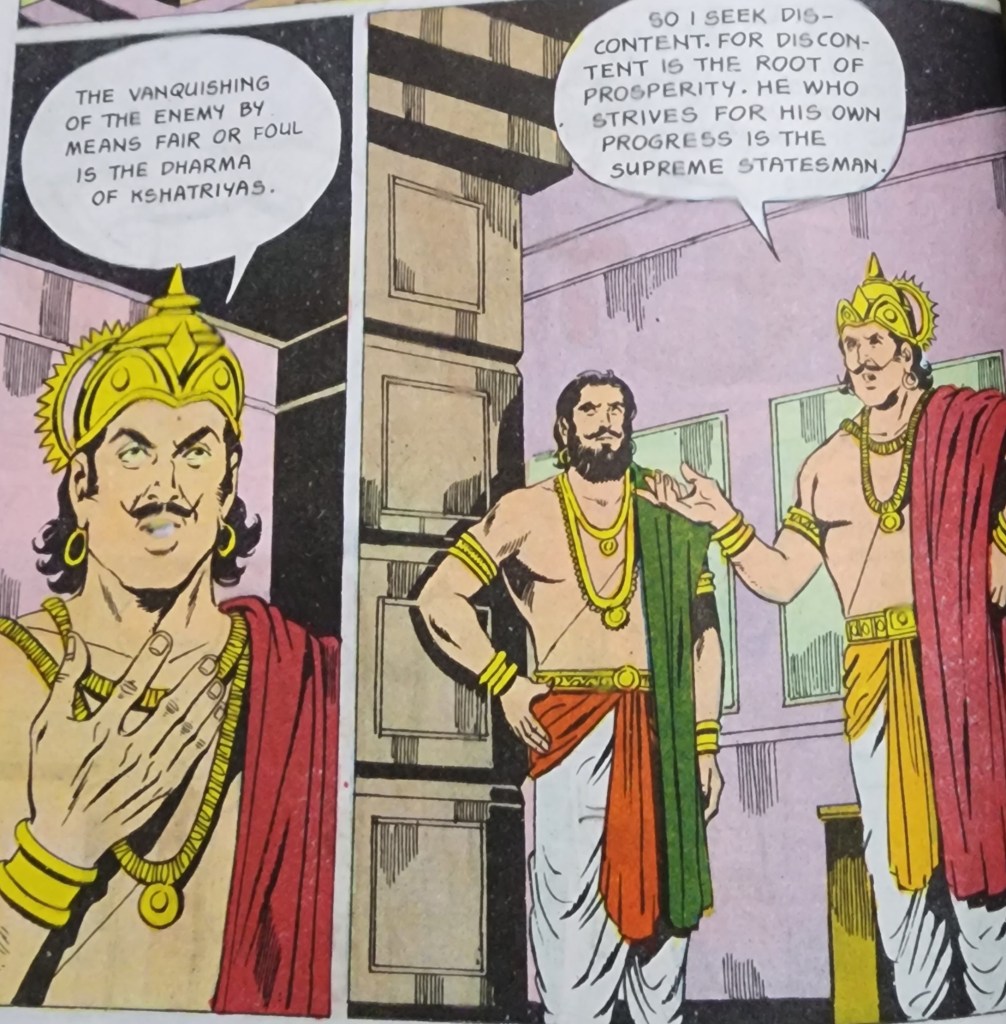

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 25 – The Pandavas at Virata’s Palace

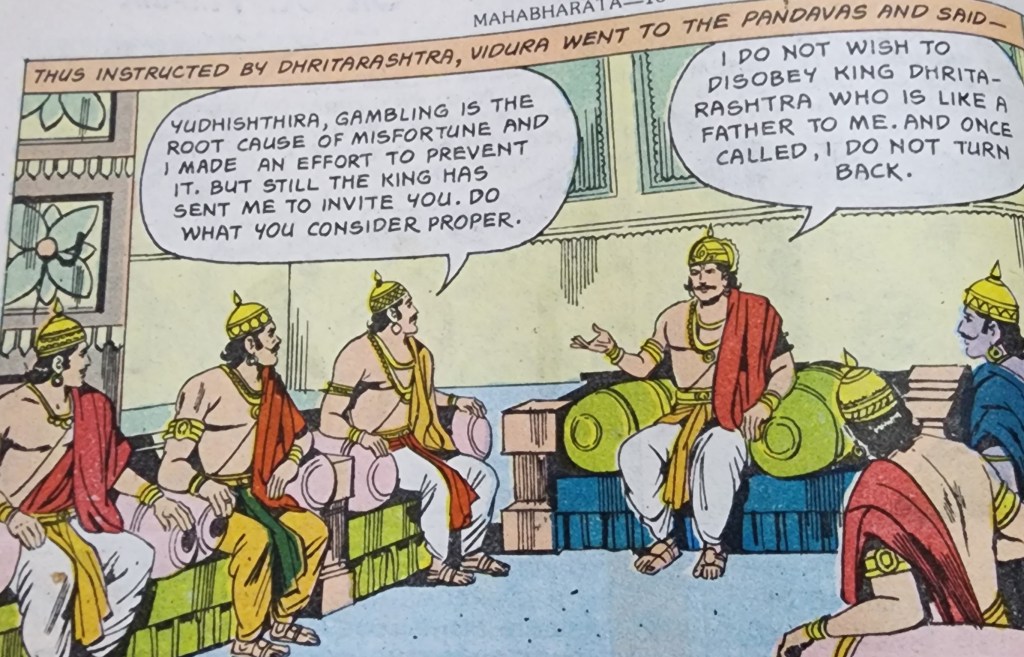

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 18- Indraprastha Lost

Yudishtira’s greatest failure is that he gambled his wife away like an asset. He also gambles away his kingdom and his brothers. His losing his brothers is perhaps the lesser of these evils because they were willing participants in the same game of dice. The gambling away of his kingdom and his wife are equally vile. He was sworn to protect and work towards the prosperity of both. This outcome also enhances the belief that Yudishtira was a bad player of the game of dice irrespective of his skills.

Do we also see the Kryptonite to Yudishtira’s superpower in the very same abilities? If he could see everything including the grey areas clearly, did the fact that he could see it all clearly, prevent him at times from doing the right thing? Let us look at the details.

Why exactly did Yudishtira not walk out of the game of dice? Why did he not fight using arms on the spot? Why did he even place his brothers and wife as objects to be gambled away when he had already lost his kingdom? Let us see if we can arrive at reasons to explain this behaviour of his.

Yudishtira had completed the Rajasooya Yajna successfully a short while before the game of dice. This Yagna had been performed with active support and positive participation by the sons of Dhritarashtra and all the elders of Hastinapura. This list included Shakuni. Did their participation make him believe they no longer held ill will towards the Pandavas? And did he believe that this put an end to the saga of the house of Lac from their youth? Perhaps he did.

In order to perform the Rajasooya Yajna, the Pandavas had carried out military ventures in all four directions. During these, they had militarily defeated many other kingdoms and if not, at least collected tributes from all of them. This wealth was used to perform the Yajna. During this time, Hastinapura had not taken the opportunity to cause them trouble or invade Indraprastha. This despite the land on which Indraprastha stood, was originally Khandavaprastha, a part of the kingdom of Hastinapura. The Kauravas had not attempted to reclaim a now prosperous kingdom when its greatest warriors and armies were occupied elsewhere. Could this fact also have bolstered Yudishtira’s belief in a lack of malice on the part of the Kauravas? Also, perhaps after the military success before the Yajna and the victory over Jarasandha, did he feel Indraprastha was as powerful as Hastinapura? Both the beliefs seem valid based on the facts.

Vidura, an extremely wise man, and prime minister of Hastinapura was the messenger who invited Yudishtira and the Pandavas to Hastinapura for the game of dice. He did warn Yudishtira of the plan by Shakuni to win Indraprastha as a wager in a game of dice, instead of using military might to do the same. So, Yudishtira knew of the ill will and the plan to circumvent any equivalence between the two kingdoms in military capabilities. But the invitation was from Dritharashtra, Yudishtira’s uncle and father figure. Plus there were other elders at the Hastinapura court who were capable of reigning in Duryodhana and Shakuni. So, weighed against Vidura’s warning, his recent experience, and faith in the elders could have suggested to him to adhere to Dharma. And this was very important to him as we have seen. His Dharma was to neither reject the invitation to dice and lose face as a coward nor to disrespect the invitation from his father figure and be seen as one who disrespects his elders (the one who gave him half a kingdom in this case, despite the circumstances at that time).

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 18- Indraprastha Lost

This overall reasoning could have led him to accepting the invitation to Hastinapura and to his participation in the game of dice. Once there, he was conscious of his duties as an adherent of Dharma to hold to his word. Hence, he stayed at the game while losing everything he never had a real right to lose (at least by modern standards), lest he be considered one who fails to stay at the game, as he had given his word to do.

Now, there could be a more mundane explanation for this. At the time of the game of dice, Indraprastha was a young kingdom, which was prosperous due to the Rajasooya Yagna. Jarasandha had been defeated, and his young son Sahadeva (not to be confused with the Pandava brother) was an ally of the Pandavas. But he was only a new king and not renowned like his father. The Matsya kingdom was not an ally of the Pandavas as yet. Manipur, whose princess Arjuna has married and had a son with, was not an actual ally as there were not relations between them and Indraprastha, and Arjuna’s son there was considered an heir to Manipur, not a prince of Indraprastha. Similarly, Arjuna’s other wife among the Nagas had not earned them an ally, as there was no relation between the Nagas and Indraprastha, and Arjuna had only spent a very short time with his Naga wife Uloopi! Also, we do not know how the other kingdoms the Pandavas had confronted militarily (extracted tribute from) during the Yagna felt towards the Indraprashta. Would they not jump at the first chance to throw off the yoke of the new emperor Yudishtira? The Pandavas had saved 84 kings from certain death when they had defeated Jarasandha, but their payback had been limited to supporting the Rajasooya Yajna, not fighting Hastinapura. So, the Pandavas had no allies to rely on immediately, when they were in the heart of Kaurava power. Add to this, the Kauravas had considerable military allies of their own.

But most importantly, all of this was before Arjuna acquired the vast array of divine weapons. That happened when the Pandavas were in exile. Arjuna acquired the Paashupatastra from Lord Shiva and a host of other weapons from all the Devas while in Devaloka assisting them in the fight against the Kaalakeyas and the Nivatakavachas. Hence, the Pandavas were not really as powerful as they would later be.

So, if Yudishtira had decided to pull out of the game of dice or decided to fight the forces of Hastinapura without any army of his own at his back in a hall full of Hastinapura forces, would they have survived, let alone prevailed? It certainly is doubtful. This could perhaps be the same reason for which they did not fight back right after the events of the House of lac, when they were weaker still, with not even Panchala as an ally. Futher, we do not know if Yudishtira had sufficient troops to help him at that point in Hastinapura. Also, if a king loses a kingdom in a wager, is his army still his own or does it now belong to the victor in the game of dice? We have no idea. But considering that even the venerable Bheeshma is uncertain of what Draupadi can expect when Yudishtira is a slave of Duryodhana’s after having lost, such a doubt is warranted regarding the army of Indraprastha as well.

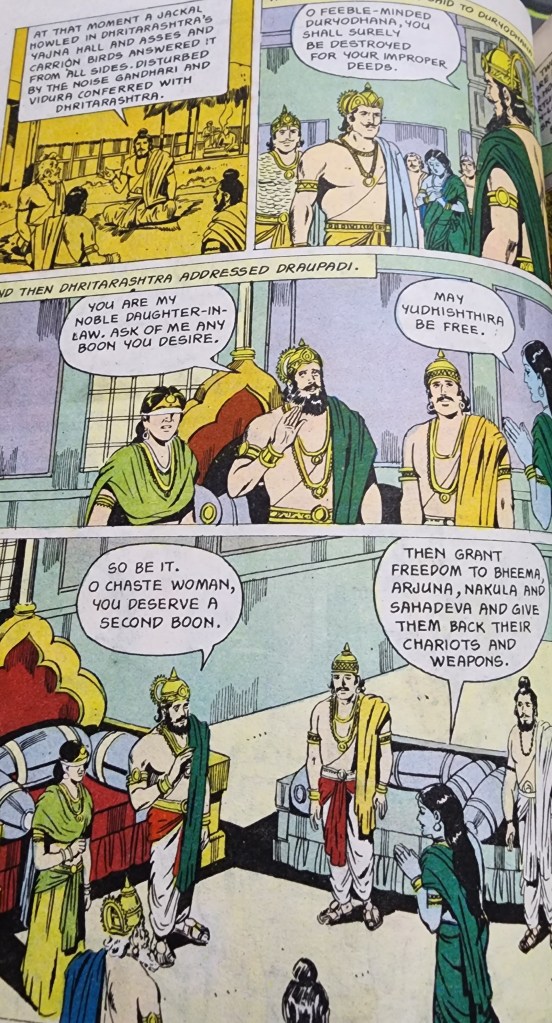

Thus perhaps, Yudishtira did see everything clearly and while becoming vilified down the ages, made the right decisions to survive, while putting faith in the elders of the Hastinapura court. And his faith turned out to be correct! It was the intervention of Vidura and Gandhari that saved them all. The famous elders like Bheeshma, Drona and Kripa failed to protect the Pandavas, but the women saved them. Draupadi’s conduct in the face of the worst atrocity and the strength of character of Gandhari saved the Pandavas their lives, and even got all their losses, including their freedom and kigdom restored to them! So, Yudishtira’s big picture analysis was correct. The women of his household saved them all. It was just that their rescuers were not the individuals everyone expected, a different set of people who no one imagined would be able to do it. But the fact that they, especially Draupadi, went through the worst of atrocities, is by modern standards, unforgivable. Also, it was such a close thing, that this correctness borders on luck and enduring it can be attributed to stupidity. But is the adherence to Dharma not supposed to protect one from adversity? And is it not said that steadfast practice of Dharma incredibly difficult and it is in especially hard times that its practice is really noticeable? These are questions that everyone has to answer for themselves. But the evidence for Yudishtira’s “big picture” ability does hold forth. It was his superpower and his greatest weakness at the same time, for he and the Pandavas went through the worst of times due to the same big picture reasoning of his.

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 18- Indraprastha Lost

This then raises the next question of why he agreed to the next game of dice. All the points mentioned in relation to the strategic situation of Indraprastha vis-a-vis Hastinapura still hold. But there are differences. He had his kingdom, its wealth, armed forces and ability to plan for a conflict. Also, the fact that the loser of the second game would have to endure an exile of 13 years (12 in the forest and the last in hiding) was established. After this, the kingdom would be returned to the losing side, if they could escape detection in the 13th year. If they were discovered, the cycle would repeat. So, the Pandavas would be divested of their kingdom and resources if they lost. So, why agree to the game?

There is no clear answer to this. But let us consider a few details. Is it again a case where a Kshatriya once invited to a game of dice cannot decline for fear of being branded a coward? Is this more of a concern for an Emperor than for a king? Yudishtira was considered an emperor after the successful completion of the Rajasooya. So, was this concern great enough to overcome the “once bitten twice shy” learning from the previous game of pagade?

The invitation for the second game was again from Dhritarashtra. We know of the relationship between Yudishtira and his uncle. Was he indebted to him for having been responsible in returning the kingdom after the first game? So, was he obliged to play as a way to repay the favour and show respect to his benefactor? Add to this the fact that this time the game was supposed to be “fair” unlike the last time, when the game was set up for the Pandavas to lose. Was this an opportunity to avenge the defeat from last time in a like manner, an offer that Yudishtira could not refuse? Was he overestimating his ability with pagade to think he could beat a master like Shakuni this time round? Perhaps it was all of these, or maybe not. But without the benefit of hindsight, imagine what would have happened if the Pandavas had won. The Kauravas would be banished to the forest for 12 years. This means a sworn enemy is taken off the board for 12 years during which to strengthen themselves. A tempting proposition, isn’t it!?

Let is now look at the episode of the two games of dice through the lens of Budo. This might reveal some interesting explanations for the same. In the Bujinkan system of martial arts, there are two very important concepts that are drilled into all practitioners from the very beginning, and are revisited all through one’s lifetime in the martial art. These two concepts are Ukemi and Uke Nagashi.

Ukemi is the ability to “receive the ground” when one is thrown or has a fall. It is all about rolls and break-falls in simplistic terms. Uke Nagashi is about receiving an attack by an enemy in different ways. This could be simplistically called parrying an attack. But these concepts go beyond the simplistic physical practice. I remember once being told of a statement by Soke Hatsumi Masaaki made in relation to Ukemi in one of his classes. This statement by Soke said that running away and hiding are also Ukemi. I would posit that if one is protecting oneself from the elements, like saying hiding indoors from the rain or running away from working in the burning summer sun, this is Ukemi. However, I further suggest that running away from a fight or hiding from an enemy would be Uke Nagashi.

So, if Yudishtira chose to survive by not fighting and expecting someone else to save them in the case of the first game of pagade, is it not instinctive Uke Nagashi on his part? Yes, it seems wrong and cowardly in hindsight, but his being mindful and aware of the big picture as we discussed earlier did save their lives and kingdom in the end, which means the Uke Nagashi paid off. Is this not like surrendering against insurmountable odds while waiting for a favourable opportunity to escape?

Now let us consider the second game of dice. Nagato Sensei, one of the senior most teachers in the Bujinkan system has a famous saying, where he states, “Leave no opening”. This is again in reference to Uke Nagashi. Based on my experience of this statement, what he means is that when you receive an attack, your position with reference to the opponent should not only mitigate the attack that was launched, but also ensure that no second attack is possible in that instant as there is no opening for the opponent to exploit. This part is a precursor to the defender being able to negatively affect the attacker due to being a safe position from where to exploit the attacker’s openings which are exposed as a result of the first attack.

Sensei also expands by adding that one needs to lead with Sakkijutsu. Sakkijutsu is the intuitive ability to sense an attack and move to a safe position before the attack lands. This is a continuous process until the attack (not attacker) ceases to exist. So, one should be aware or mindful of one’s situation and hence be able to feel/sense/intuitively know of an attack and move to a position where one is safe from the current and future attacks and then exploit possible openings revealed in the opponent.

If we look at the situation before the second game of dice with this knowledge, things change a little. If a king has to “leave no openings” while responding to an attack against his kingdom, what does that mean? Does it mean find a safe position for himself and his family or a safe situation for his kingdom? I would suggest that it is the latter, considering that Yudishtira was Dharmaraya, who put his duty to his kingdom first.

If Yudishtira’s objective is to protect his kingdom, is it not correct to accept the invitation to dice again? If he has won the same, his greatest enemy would be out of the picture for 13 years with no cost to his armed forces and no economic cost to Indraprashta. If he lost, the negative consequences were only for the royal family of the Pandavas. The Pandavas had reaped the greatest rewards from the establishment of Indraprastha. So is it not only right that they be ready to bear the greatest cost? Perhaps yes.

Next, there is no evidence that Duryodhana was a bad ruler or a tyrant who harmed the citizens of his kingdom. He had many negative qualities, but not as a bad administrator. We will consider the negatives in Duryodhana later in this article. But considering Indraprastha would not be significantly worse off under Duryodhana, if the Pandavas lost the game of pagade, is that not a better Uke Nagashi a king should consider for the sake of his kingdom? If Yudishtira had not accepted the invitation and a war had started right then, the cost to Indraprasta would be much greater.

Also consider this. If the Pandavas were exiled for 13 years, they would have 12 years to increase their strength, plan the defeat of their cousins and retrieve their kingdom, while causing least harm to their citizens. In hindsight, only a part of this happened. Indraprastha was saved at that time, but after 13 years, the Kurukshetra war that ensued was apocalyptic. The rejuvenation of Hastinapura and Indraprastha took the investments of an Ashwamedha Yajna after the war. But without the benefit of hindsight, was Yudishtira not employing his powers of being mindful and seeing the big picture to the best possible use of Indraprastha, even if not the Pandavas? It might have seemed so at the time. The fact that Yudishtira faced up to the consequences of the Kurukshetra war much later is also testament to his being willing to live with his failures and face the consequences.

Consider this; is this whole idea of protecting people until he was able to confidently fight back militarily not similar to retreating in the face of a greater enemy until one finds favourable terrain and weather to harm the enemy with minimal cost to one’s own forces? Is this not something that Wellesley used against Napoleon at Waterloo and was this not the same tactic that resulted in the defeat of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna of Mexico at the hands of Sam Houston of the Republic of Texas? It is not the same tactic in a battle, but it does seem a similar strategy when applied to nations a whole. So, Yudishtira might have failed in his strategy (if it was that) when he accepted the invitation to the second game of dice, but based on his abilities, it might not have seemed a set result at that time.

While discussing the actions of Yudishtira, there is one aspect that we need to consider. This is more generic, with respect to the actions of all the heroes of the Mahabharatha and all their failings. This is not central to this article and not something we can go into in great detail. But it has to be acknowledged to get an idea about their perspectives, to the extent possible. This relates to the conditioning of people in positions of power during the Mahabharata age. Let us begin with Yudishtira himself.

Was Yudishtira not aware of something called “Aapat Dharma”? The rules (or lack thereof) that come into picture when one’s life and means to survival are threatened. This would have allowed him to not participate in at least the second game of dice. From the little that I know, “Aapat Dharma” or “Aapadharma” suggests that what is “Dharma” or “what is the correct thing to do” changes from when there is no threat to life and means of livelihood to when one is desperately trying to stay alive or save one’s family and means of livelihood.

When things are not life threatening, one needs to follow rules one accepts as Dharma more stringently. When one is under threat, these can be done away with, until “normalcy” is restored. Of course, definitions of “normalcy”, “threat to life” and even “Dharma” itself are subjective and change over time and geography and also with life experiences. It is just that there are some regular practices can be let go of when there is a dire situation. As an example, one might choose to be a vegetarian in one’s own civilized state/place of existence. When this civilized state is taken away, the choice can change with no guilt attached to the same. If one is stuck in a place where there is no opportunity to find vegetarian food, for a duration beyond what one can manage with less or no food, there need be no guilt associated with consuming meat. The same goes if a meat can cure one of a terminal disease.

Was the situation the Pandavas faced during the first game of dice and while reacting to the invitation to the second one not worthy of being considered commensurate with violating Dharma and invoking the escape clause of “Aapat Dharma”? At least from our modern perspective, it would seem that the answer is a resounding YES. The fact that Yudishtira did not and none of the other Pandavas did, suggests that either the situation was not “dire enough” for them to consider putting in abeyance their personal definitions of Dharma. Or, the consequences of the loss of reputation one faced by taking recourse to “Aapat Dharma” was too much to even contemplate the same.

Consider this same situation with a few other venerable characters from the Mahabharata. Bheeshma refused to break his vow of celibacy when he knew he was the best candidate to take over the throne after his half-brothers were dead without any progeny. This was despite his step mother, Satyavati, herself asking him to do so. And Satyavati was the reason for his taking the oath in the first place!

Drona fought for Hastinapura as they helped him earn half the kingdom of Panchaala. Even before this they gave him a job when he was down on his fortunes. Kripa, Drona’s brother-in-law, stuck to Hastinapura’s side in the Kurukshetra was, due to loyalty. Neither Kripa nor Drona was bound by any oath.

Lastly, Karna stuck with Duryodhana because he had stood by him when he was insulted in the demonstration arena by the Pandavas. Even after he was told that he was the eldest Pandava in secret, and this meant he could end the war before it started did not convince him to change sides. He fought the war and died without ever revealing this fact to those who mattered in the war. Also consider another event with Karna. He was known to donate anything anyone asked for after his morning Sandhyavandana. The fact that he never refused anyone at this time was very important to his reputation and he was called “Daanashoora” Karna due to his generous nature. Indra, the king of the Devas, used this firm and predictable behaviour of Karna’s to ask him for the Kavacha (armour) and Kundala (ear rings). The Kavacha and Kundala of Karna’s were divine in origin, coming from Surya, the Sun God. These made Karna impervious to any weapon. He was undefeatable as long as he possessed these. If he had not given these away, it was very likely that the Pandavas would have lost the Kurukshetra war. Yes, he gave them away as his reputation was more important. Of course, he believed he could turn the war without the same and he also believed the Kauravas would win the war. Hence his being revealed as a Pandava was likely more trouble after the victory. But with the benefit of hindsight – he died, the Kauravas lost and he passed on the chance to stop the Kurukshetra war from happening. A lot of human misery followed.

Kunti, the mother of the Pandavas and Karna, did not reveal the truth of his birth to prevent the war either. She did this as Karna asked her not to. They had another agreement which is not very important for this discussion. Similarly, Krishna knew of this secret as well and chose to not reveal the same. He only urged Kunti and Karna to do so. Of course, Krishna is divine and made choices for which he and his clan paid, through the curse of Gandhari, many years after the great war. His thinking is not something one can attempt to decipher.

There is one common thread in all of this. All these folk are terrified of breaking an oath, or a decision, once taken, even if their choice serves something terrible about to transpire. This is because they were all obsessed with their legacies. Their reputation was more important that the consequences to millions of other common folk because of their choices. This issue is seen in Greek mythology as well, where Achilles decided to participate in the Trojan war to build his legacy and fame despite being certain that he would meet his doom there.

This is an aspect Krishna demonstrates as not really Dharmic. One needs to learn to accept vilification if that serves the greater good. He chose to be called “Ranchod”, one who runs away from a battlefield, in order to defeat Kaala Yavana. He also chose to leave his city of Mathura and relocate with the entire populace to Dwaraka. This was to protect his people from Jarasandha’s wrath. He also chose to accept the curse from Gandhari as punishment for not preventing the war. He definitely tried to make people change their thoughts and ways, but did not use his divine abilities to do so. This is apparently to let things take their course with just human actions.

In the Bujinkan, we are taught a concept called “Jokin Hansha”. This refers to “weakness due to a conditioned response”. As an example, consider the fact that we do not do something even in if we realize it to be the right thing to do. This is likely because we “think twice” and decide it is wrong as it goes against what we are expected to do or is tradition (or something similar). This could lead to an adverse outcome. This is the consequence of “Jokin Hansha”. Consider a simplistic example. You do not want to shake hands with someone. Yet if that person extends a hand, we take it. We do not do a “Namaskaara” because we assume the other person might be offended. Conditioning is as pervasive as this and Jokin Hansha refers to negative consequences that occur from actions even as simple as this. Breaking conditioning and doing what one wants to in an environment where conditioned responses rule, has consequences we may not be ready to face. This, on a grander scale is what the heroes of the Mahabharta faced and failed at.

Now, we have considered the strengths of Yudishtira, his weaknesses and potential reasons for those. His adherence to Dharma, his consultative vein and abilities are demonstrated. While all this explains his actions before the war, what makes him a better candidate to be a king as compared to Duryodhana? We shall try to explore this in the following section.

As mentioned earlier, while Yudishtira was more of an introspective person focused on the big picture and adherence to Dharma, Duryodhana was primarily a warrior, who also wanted to be king. There is no indication that Duryodhana was a bad administrator. So, where is the difference between the two?

Duryodhana had one advisor in Shakuni. Duhshasana and Karna were more members of his coterie or mutual admiration society. They were not relevant to dissuading him in any action and did not specifically point out his flaws. Shakuni’s advice was driven by a motive to destroy the Kurus from the inside in order to avenge what he saw as injustice to his sister and his kingdom of Gandhara. Moreover, from what I know, Duryodhana never considered any advice that clashed with his own world view, from any of the other elders in Hastinapura. This shows that his perspectives were not as considered as those of Yuishtira’s. They were what he wanted them to be. He also had never seen the world like Yudishtira had on multiple occasions, while living among the common folk in his early childhood and after the events of the house of lac. He had not endured the hardships of the forest like the Pandavas either.

So, Duryodhana’s vision of Dharma was not exactly based on a “big picture” but what he wanted it to be. This made him a potential agent of chaos. Also, his ego prevented the chances of his ever changing his ways. The man held grudges over a long time, and was single minded in trying to achieve his objectives. While being driven towards one’s objectives is an admirable quality, a king might not have this luxury. His drive could be dangerous to those around him and the country as a whole.

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 18- Indraprastha Lost

It was Duryodhana’s desire to obtain Indraprastha, subjugate and humiliate the Pandavas and not return the kingdom after 13 years that was the root cause of the destruction of a very large number of lives from several kingdoms during the Kurukshetra war. Of course, it can be said that his being laughed at in the magical hall built by Mayasura in Indraprastha was the reason he wanted to take everything away from the Pandavas. But are the cause and effect commensurate? In modern thinking they are not. But, even by the standards of the day, when personal reputation was above all else, was it warranted? Even if we assume it was, his ability to not adapt to the changing scenario of the situation and being unmindful of the consequences was disastrous. This of course was due to his not being consultative. So, he was never a big picture guy, and thus, could never put his kingdom first, and thus never put Dharma first either.

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 18- Indraprastha Lost

Lastly, Durypdhana had no ability to “let go”. Something we are taught as martial artists is the ability to let go of anything that is not “worth it”. This can be a position, a technique or a concept we are trying to apply to any fight. An example here might be the following. If strength is not working against an opponent, let go of applying the same and try to take her or his balance with a better position. This is true in any conflict management situation. If negotiation is not working in a conflict between nations, they will let that course of action go and consider covert application of force or an overt display of forces to nudge the negotiation back on track. There need be no guilt associated with letting go of a course of action to pursue something else which has a higher probability of ending a conflict. This was something Duryodhana never could do, while Yudishtira did it all the time.

Image credit – Amar Chitra Katha Mahabharata – Chapter 18- Indraprastha Lost

An example that comes to me vividly about this from recent history is as follows. I remember reading an article a long time ago. I think it was in the early part of the 2000s. I think it was in the newspaper, The Hindu, but I could be wrong. It was about the LTTE failing at negotiations with the Lankan government because it was beholden to the past. Apparently some members of the LTTE felt a negotiated settlement would betray their dead and their sacrifice would be shamed by the same.

In conclusion, Duryodhana, while not being a bad administrator, was a potential source for perpetual conflict. Also, his inability to consider contrarian points of view and ego mania made him an obstacle to any positive change. This is what made him an enemy of Dharma, which, in the epic, is all important. Hence a Dharma Yuddha, with Duryodhana as the antagonist. He was not a mustache twirling villain, or a specifically bad king, but a definite threat to Dharma.

Notes:

1 Mahabharat Ep 42 (watch between the 13 and 16 minute marks)