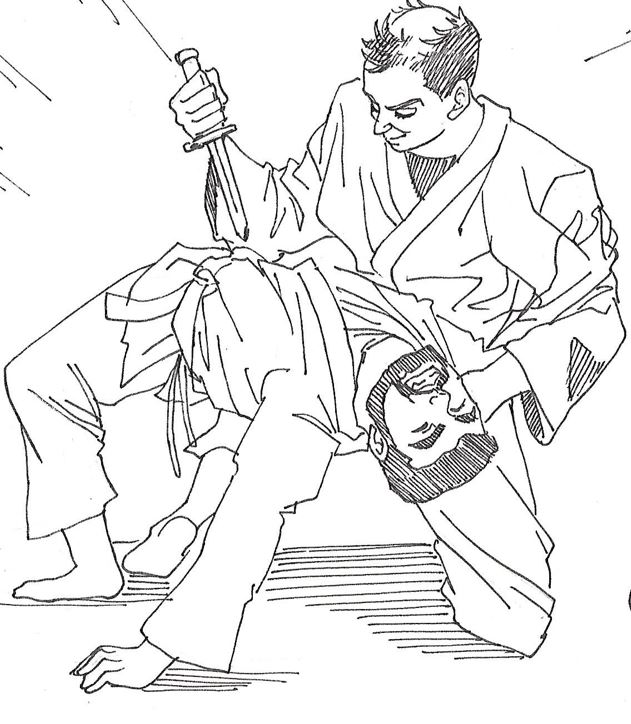

Training with knives is scary. It is scarier than training with swords or spears or sticks. I am of course referring to traditional martial arts and not considering fire arms or even historic projectile weapons like bows and arrows, crossbows, slings and other thrown/discharged weapons. In other words, using Bharatiya terms, I mean while training with shastra and not astra.

The knife is not scarier because a knife is more dangerous than the other weapons. It is scary because, one, it can be invisible until after the attack is complete, and two, because being a close quarters weapon, a knife, even when detected gives very little time to defend or protect oneself against.

I have been told by mentors with far greater experience than I in the martial arts, and some with practical experience in fighting with and defending against knives, that the numbers bear testimony to the fear of knives.

I am going to add the numbers that I have heard, as part of the notes below. This is because I have not personally done any analysis of knife attacks. I have only read articles about the research and heard people who have done the same share their knowledge. So, what I have is secondary or tertiary knowledge at best, about the numbers and statistics related to knife attacks. Also, my personal experience is more with traditional martial arts and larger weapons that I referred to earlier in this article. Add to this the fact that there are varying views about knife attacks, and surviving the same, and that these sometimes disagree with each other, I do not want to subscribe to any one view. That decision is personal for everyone, because it involves physical injury and trauma. I apologize for this inconvenience, and also request readers to do a little back and forth scrolling while reading this article.

Another worry with knives is that a slashing attack might look ghastly but not be fatal, while a stab shows a smaller wound but is far more likely to be fatal. So, to repeat myself, knives are dangerous as everyone knows, and are scary to train with, even when they are fake (because the knowledge of the danger is real).

The numbers seen in the notes below, show that there is no clear, sure shot defence against a knife attack. So, it is a situation with no solution. What does one do in a situation like this?

What I have heard from people with knowledge and experience with the problem of the knife, state that the best solutions are one of the following. One, avoid the fight or get away from the fight, in other words, retreat and get away from the space where the knife is a threat. A large distance between the knife wielder and the potential victim is a safe solution to survive the knife. There is a drawback to this solution though. Based on what I have understood, the chances that a knife attack begins only when the assailant is very close is very high, and hence, the opportunity to either run away or put a lot of distance between oneself and the attacker might not always present itself.

The second solution is not a different one, but more an extension of the first. It is to not be in the space where a knife attack might occur. This is similar to (though may not be exactly the same) what is also called “situational awareness” by some martial art systems. Yes, this might sound philosophical. But it is based on primeval intuitive abilities of human beings, which helped avoid predators (human and otherwise).

This is not something new either. Anyone who has traveled alone and late, in the dark, will know how one’s senses and ability to expect threats are heightened. This same feeling can be accepted and hence practiced in situations that do not exude an explicit threat with atmospherics (like a pub or a festival gathering where attacks are not expected). This could also be made mundane by saying, trust your feeling and do not go someplace you do not feel like going, even if the not wanting to go is not due to a threat perception. It could be unease manifesting as fatigue, lethargy or any other “I don’t feel like going there”.

The above alternative is about trusting one’s intuition and not being afraid to retreat. It can further be said that trust in intuition is very important, not just during knife defence, but also in staying away from a situation where defence against a knife is necessary. This might seem a cop out to some because it reduces the emphasis on practice to survive against a knife. They are not wrong. Practice is perhaps the best defence. But then, several people do not have the time to expend on the requisite practice, unlike those imparting the training or those in the police, armed services and other security services.

When practice and training time is a premium for most people, focus on the ability to avoid a fight is vitally important. Also, this is not surprising, in my opinion, for this is how we deal with most problems at work as well. And work is a very important part of all our lives, while self-defence training might not be.

Consider how much all of us rely on intuition to solve problems at work. All of us, when we are applying or developing any solution to any problem at work have a “gut feel” about how difficult the development will be or how long the same will take. All planning and estimation works on this. Also, the need to be on the lookout for problems after applying said solution is also based on estimations, which are driven by intuition. After all, intuition is experience plus a sense of the context/situation/atmospherics around a problem. Hence, we know when to apply a temporary fix as against a permanent solution as well.

The use of intuition at work from what I stated above, is about not just solving problems but also about being aware of the consequences of a solution as well. Thus, we are not only working to solve a problem, but also trying to protect ourselves from the consequences of further problems that might come up due to the solution, especially if it is a temporary fix. The key phrase here is “protect ourselves”. This is using intuition and stepping back to protect oneself; not defend against a situation, but to stay protected at all times. This is akin to wearing a helmet whenever you ride a two wheeler and not only when you are on a bad road or in heavy traffic.

This is the same as trusting one’s felling about a place or situation and also about retreating when faced with a situation where there is no good defence, like against a knife. Thus, protecting oneself is as important as, if not more important than a good defence. This rings truer still when a defence might be designed with a set of assumptions (which is always the case when defensive training is based on specific situations). In other words, protecting oneself starts with trusting one’s gut feeling and the ability to retreat before the need to apply a defence.

There might be no measure to check how many times one protected oneself by not being in a place or situation where a defence against a knife might have been necessary. But then, that is the best defence anyway.

On a lighter note, at least for us Indians, retreating to protect either oneself or ones dear to any individual should come naturally. After all, one of the many names of one of our favourite Gods, Lord Krishna, is “Ranchod Das”. It means one who runs away from a battlefield. This was anathema to the warrior code of the Kshatriyas (as is common in many warrior cultures around the world). I will not go into the story here, but Krishna chose the insulting moniker over fighting an impossible battle (against Kaala Yavana). He of course, survived and won the battle as a consequence of the retreat; but the name stuck.

In conclusion then, training survival against a knife has to include training to retreat (run away) and trusting one’s intuition until a defensive solution can be found (an offensive solution might also be possible, but hurting another person brings with it a host of other problems to consider after the act).

Notes:

- I have been told that if an unarmed individual is attacked by a knife wielding assailant, and the person being attacked knows of the attacker’s knife, the probability of surviving the attack unharmed is between 0 and 0.5%. This is if the person being attacked has no training in defence against a knife. If the person being attacked is trained in defence against a knife, the probability of surviving unharmed apparently goes up to around 2%. So, the probability of surviving unharmed against a knife is 2% AT MOST, with specific training to defend against the same. This is of course, supposedly not considering body armour to protect an individual against knife attacks. This number is undoubtedly low but 4 TIMES greater than with no training. Nonetheless, the number reinforces the worry about training with knives. Little wonder that knife training is done with fake knives only! 😛

- A 1988 book by Don Pentecost called Put’em down, take’em out! Knife fighting from Folsom prison. – I have heard that this book is supposedly contentious and should perhaps be considered as another source of information and not as gospel truth. Also, I have not read this book myself and have only seen references to it.

- Some interesting articles I have read online on the topic of knife attacks and protection against the same are mentioned below. These articles refer to the book mentioned above.

- There are many YouTube videos referring to knife attacks and what one can do in such a situation. I cannot specifically recommend any, but leave it to interested viewers to decide on the information they find most useful.

- There are also people who opine that even screaming for help or running away need to be learnt and practiced. These two might seem to be common sense, but in a stressful situation like a physical assault, they will not manifest automatically. Practice and conditioning are what a person falls back on in such a situation and hence this suggestion. This is beyond the fact that a knife attack might not allow for the option of running away.

- Knife training can be used for life lessons, but the vice versa need not be entirely true. This obviously, is because, a threat to life and limb is very real in a knife fight, while the same is not true at work or in others aspects of life that are not physical combat. In life and at work, the risk could be financial, to one’s health and one’s reputation. The opportunities available to fix these, can be greater for everyone, when compared with a short and intense knife fight. Hence, what I have opined here is a perspective more relevant for individuals that are not martial arts’ practitioners or students who have just begun martial arts’ training. If this was looked at from the perspective of someone who is a regular student of the martial arts, I would opine that the learnings from training the knife and protection against it, including the aspect of intuition, should be a take away to be applied in life and work.