The Dashāvatāra – Balarāma is included instead of Buddha in the above image

In my previous article I attempted to explore martial art concepts that can be gleaned from the festival of Deepavali. This is a continuation of the same. Here, I will delve into the concepts that I could not consider in the earlier article as it was already very long. It might be useful to read the earlier article before getting into this one. But in case one does not, this article can be read as a standalone. The link to the previous article is seen in the notes below*.

A good starting point to delve into these concepts is the Dashāvatāra. The Dashāvatāra are the 10 incarnations (Dasha – 10, Avatāra – incarnation) of Lord Vishnu. This is not to say that there were only 10 avatāras of Lord Vishnu. The most popular list of incarnations of Vishnu is of 10 and this has been so for a few centuries based on the little that I know. If I am not wrong, there are also lists of avatāras that have 23 incarnations. The avatāras that are a part of the Dashāvatāra are not always the same.

Based on my understanding, the first 7 incarnations are the same in most lists. These are,

- Matsya (1st), Kurma (2nd), Varāha (3rd), Narasimha (4th), Vāmana (5th), Parashurāma (6th) and Rāma (7th)

Of the remaining three, there are differences of who are considered the avatāras. I am sharing below a couple of the variations that I am aware of.

- Balarāma (8th), Krishna (9th), Kalki (10th)

- Krishna (8th), Buddha (9th), Kalki (10th)

The list with Buddha is the most common one that I am aware of. There are opinions where Lord Panduranga and Lord Jagannath are a part of the Dashāvatāra and not Buddha.

For the purposes of this article am going with the 10 incarnations where the Buddha is included and not Balarāma, simply because that is the one I was taught as a child and not because I am sure that that is the correct list. Also, I am sticking to only 10 avatāras and not considering the lists which have more than 10. Again, this is only because I do not have extensive knowledge about these.

Each incarnation had a specific purpose. I am adding a sentence or two about each avatāra and the purpose of the same in the notes below**. I am also adding a couple of examples from beyond the 10 incarnations where an incarnation or form of a God or Goddess eliminated a specific problem. I am going to be referring to these to make the points in the article, but the little detail is in the notes to try and keep the article to a “reasonable” length. 😊

The exact purpose of each of these avatāras is mentioned in the notes. But in general they fall into one of two categories, as far as I can tell.

- Protect and save people from a tyrant.

- Preserve the ecosystem, which includes the guardians of the same, which is why the Devas, who are the Lokapālas or guardians (of natural phenomena), are saved every time. If the Lokapālas are affected, the ecosystem is affected, and hence the people.

Considering the above, the objective of every avatāra has very high stakes. If the stakes are very high, how are the problems resolved? Yes, violence is one solution. But violence is neither the only solution nor the preferred one. Let us consider the other solutions that were employed by the avatāras.

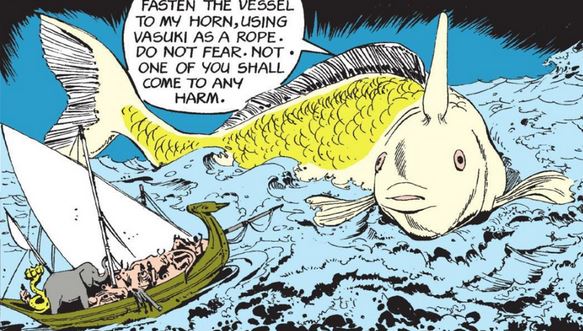

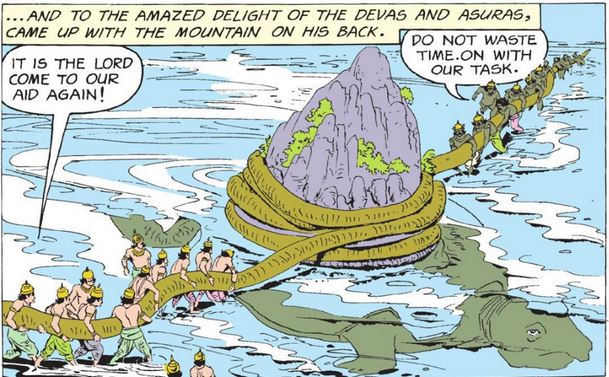

- The solution by the Matsya and Kurma incarnations were two-fold. One involved identifying leaders who could bring people together for specific enterprising activities. The second was providing support to an engineering project of epic scale against enormous environmental adversities. So, they were perhaps Management solutions in modern day terms.

Matsya (L), Kurma (R)

Credit for the images – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, Kindle edition

- The Varāha, Narasimha and Parashurāma avatāras were warriors who used violence to solve problems. Varāha & Narasimha were protective warriors. Lord Parashurāma went on to spread the knowledge of the martial arts after his task as an avatar was complete.

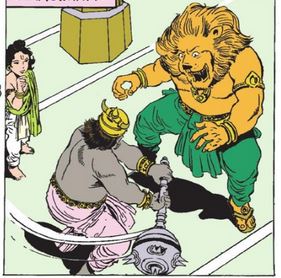

Narasimha (L), Varāha (Top R), Parashurāma (Bottom R)

Credit for the images – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, Kindle edition

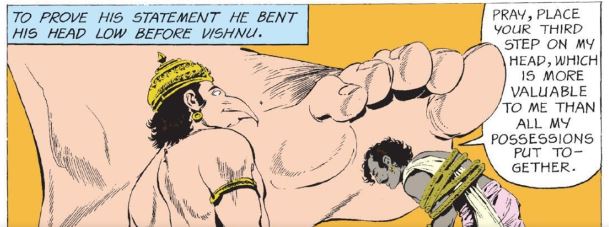

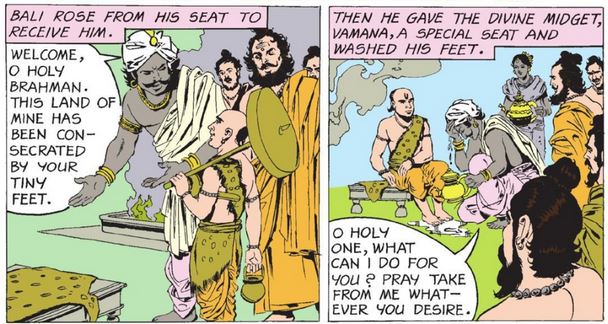

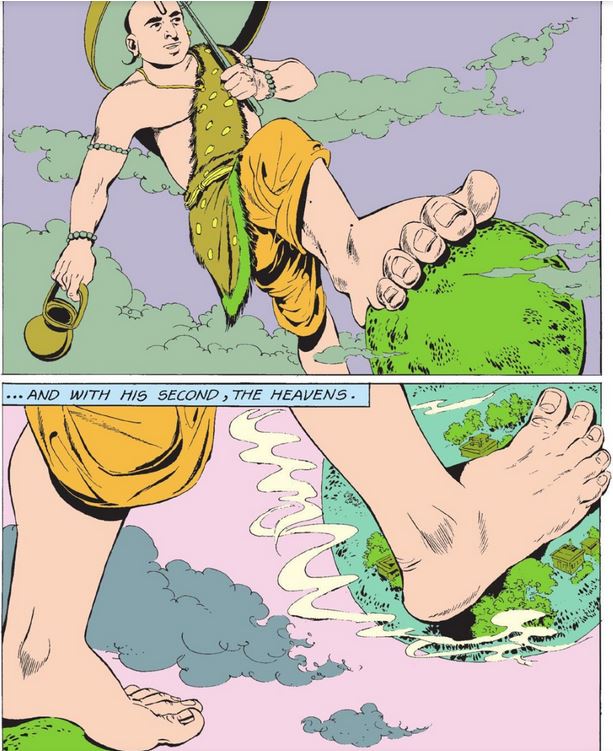

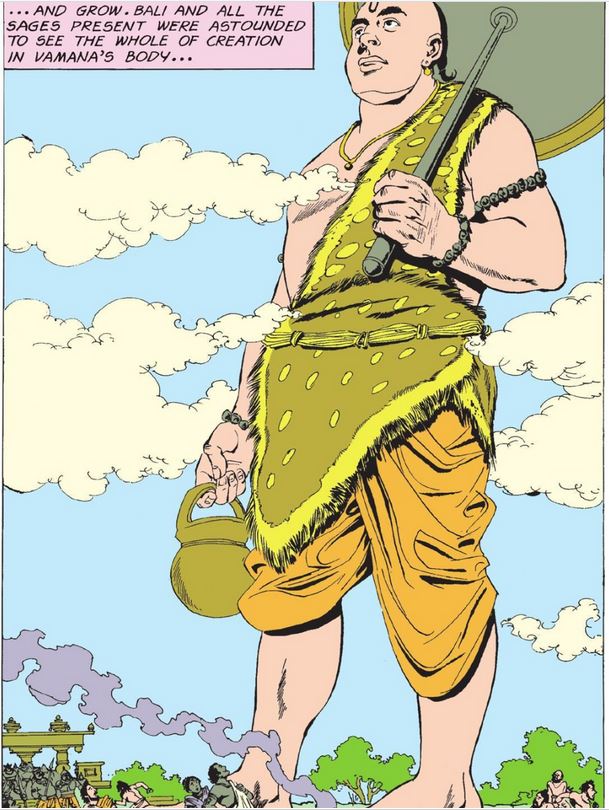

- The Vāmana incarnation was about deception and negotiation. It specifically abhorred violence. It was, by modern day standards, the signing of an inter state agreement (peace treaty in other words).

Vāmana

Credit for the images – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, Kindle edition

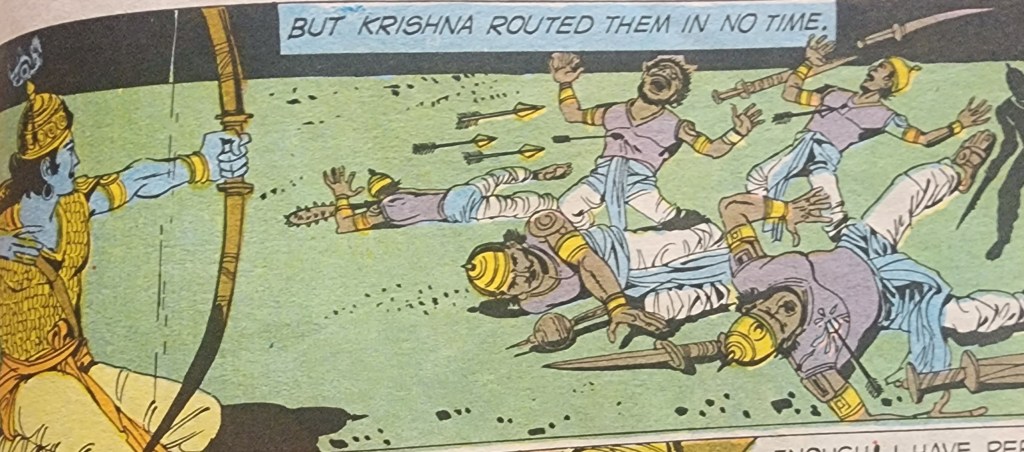

- The Rāma, Krishna and Buddha incarnations of Lord Vishnu lived a life that could serve as a case study. These incarnations served many purposes and hence used many solutions. During their lifetimes, they used administration, violence and negotiation to solve problems. It is almost like these incarnations combined all that was used by earlier avatāras. Their lives served as examples when they were no longer present in their mortal form. So, storytelling, entertainment and case studies were also a part of the plethora of solution types that they used. Considering that these options need documentation, add that to the list as well, as these are potential solutions that can be used by populations for centuries to come. The documents include, the Ramayana, Mahabharata (including the Bhagavad Gita) and the teachings of the Buddha.

Rama (L), Krishna (Top R), Buddha (Bottom R)

Credit for the images – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, Kindle edition

The above also apply to the other examples I have mentioned in the notes, which are not incarnations of Lord Vishnu. That said, the information regarding all the avatāras have also reached us through stories. And we can identify that the solution used in the stories fits into any of the categories mentioned because we still use the same in daily life. Of course, the violence in daily life refers to displays of anger and disappointment, which could constitute emotion or intellectual violence. This is a lot more common in our lives, compared to the use of physical violence.

So, if we say we use management and administrative solutions (processes), violence (non-physical), engineering and storytelling (documentation, presentations and meetings) on a daily basis, another aspect becomes clear. We use all of these without specifically thinking of the same. We use them in any combination as required, according to the situation. We do not actively classify what we do into the silos I mentioned. The classification is only in hindsight. This means that we do “whatever we need to”, “however we can” as the situation demands.

“Whatever we need to” and “However we can” are key aspects of the martial arts. This means exactly what it sounds like in the context of a physical conflict, with or without weapons being involved. One does whatever one has to, to survive however one can. All the training and experience comes down to be being able to use all the learning, intuition, learning, techniques and forms in a short duration to come out of the situation alive and with as little physical injury as possible.

There is no conception of what technique is being used in a real situation. The body reacts thanks to all the training, and does whatever it can instinctively, even if it means to escape from the place. Escaping only means that all the experience paid off in being able to identify that a fight was simply not worth it. This is especially true if one has around, people or things very dear to oneself when the fight begins. Seldom can one protect oneself and others, especially if weapons or multiple opponents, or both(!) are involved. Before the escape happens, what is done instinctively based on one’s training is never a specific technique or form, it is a variation or combination of what was learnt over the years of training.

This is true even in the case of combat sports, just that one does not need to escape. There are rules, weight categories and time limits to prevent life threatening injuries. The competitors still use variations of what they have trained. They “feel” the fight and flow with whatever can be done to win the fight.

Most martial art practitioners realize this pretty early on, if they are training regularly. My teacher and couple of my mentors repeat this incessantly in class, in case one does forget. One hears, “do whatever is necessary” and “however you can” time and time again. They in turn heard this from their teacher, all the way back to Soke Hatsumi Masaaki, who drilled in this idea for most practitioners in the Bujinkan system of martial arts.

This notion can be expanded further. I have heard this said from the same people mentioned above, “Don’t depend on the waza in a real situation. Kata will get you killed.” A simple way to put it, in my opinion, would be, “Learn the form to gain the concept. Use the concept to adapt. Adapt to do whatever is necessary. Do whatever is necessary, however it can be done. Do it however you can, to survive.”

Another statement with a similar meaning is “Don’t depend on the book. The book will not fight for you (or the book will not save you)”. The book being referred to here is the book with the details of all the waza (technique) or kata (form/set of forms) and how to perform the same. “The books” might protect you, like how Shaastra or Bun (knowledge) might protect you. It is more like saying “The library of knowledge” will save you. But one book of techniques will not! So, don’t fall in love with waza or kata, because they can’t save you. Fall in love with waza and kata as doorways or pathways to experience, awareness, knowledge; all of which enhance the probability of survival in a physically threatening situation. An extension of this is to not think any martial art or style is “the best” or to think one must support it no matter what, simply because it is the style one trains.

One Japanese phrase that I have heard from my teacher and some senpai during training is “Issho Khemi”. I have heard two translations for this phrase. The first is “do just enough” and the second is “do whatever is necessary”. The second translation is literally what we discussed earlier. When the first translation is implied, in my experience, it is used in the context of reminding one to not get bogged down in trying to use a fixed technique or movement.

In any conflict, whether physical or otherwise, the opposing sides do various things. It is extremely rare for any one side to be able to predict, read and plan for all the actions of the other side. And if this is possible by some extraordinary fluke, executing the “perfect plan” exactly as intended is as difficult and rare as the making of the same is. This is easy to see in a one-on-one fight. A given technique might work on an individual. But the same might not work on another person and the same might not work on the same individual at another time, maybe not even in the very next instant. This is true even while training that specific form, let alone in sparring or a real situation.

So, a given technique needs to be modified (applied as required) from person to person and every time it is executed. This means that if a given technique does not work, one should move on to something else and keep repeating this iterative process until something works. This means two things. First, identify when something is not working. This in turn means not expending too much effort on trying a single way of doing a specific technique. Secondly, it means that when a technique works, it usually does not require too much effort. The identification of the effective technique might be harder than getting said technique to work.

These two notions mean that one should do just enough to verify if a given technique will work, and if that is not sufficient maybe it is time to try something else that might require just sufficient effort. In either case, it is not useful to develop tunnel vision in making the execution of a technique the objective. The real motive is always to survive by doing what is necessary, however that can be done, not to determine the effectiveness of a given technique.

I remember that a few years ago Soke Masaaki Hatsumi had displayed in the dojo, calligraphy by Yamaoka Tesshu. These were acquisitions of his and he had used the writings as an inspiration for that particular class. Yamaoka Tesshu lived in the second half of the 19th century and was an advisor and teacher to the then Japanese emperor (I think it was the Meiji emperor). He was also a sword master who taught at his own dojo.

There is a book by author John Stevens, which is a biography of Yamaoka Tesshu. The book is titled “The Sword of No-Sword: Life of the Master Warrior Tesshu” (link to this book is seen in the notes below)***. In this book, as I recall, there is a very interesting observation made by the author. He says that when Tesshu was teaching his students, he always exhorted them to train harder. But he never taught or focused too much on specific techniques and forms. In other words, Tesshu wanted his students to focus on training as a whole, not consider mastering individual forms or techniques one after the other and use them as stepping stones. This idea along with the tile of the book makes me think that the focus was on the situation and what one could do in that time and space. This is the same as “Issho Khemi” and doing “whatever is necessary”, “however one can”.

So, we see that the Dashāvatāra from Hindu tradition and the martial arts have concepts that are the same. The concepts relate to problem solving and surviving a situation. Is this seen in modern life as well? I would say yes. I will share an example and my observation regarding international diplomacy and then get back to life in general.

In modern day diplomacy we hear the words, “based on shared values”. Considering that all nations only work in self-interest, the words should ideally be “based on shared interests”. But there are constituents and groups, especially in democracies, that put a great premium on “values” and expect that the leaders of their nations keep these at the forefront even when they are working towards national (self) interest, while working with other nations. If these nations do not share the value, like when democracies deal with dictators, these constituents are upset. So, realpolitik requires that the words be “values” instead of “interests”, even if it is a lie or a half-truth at best. The deal will be the same, irrespective of the words, but choosing specific words pacifies some sections of the society. So, why not use a lie to get the job done in the self-interest of a nation? After all, that is the purpose of a government, not the “promotion of values”. Has anyone ever seen the manifesto of any political party anywhere in the word state that they will work towards and allocate national resources to ensure that institutional democracy takes root successfully in a country not their own? I think not. If anyone knows otherwise, do let me know. This play of words is a case of “Issho Khemi” in statecraft.

Similarly, all of us do this in life and at work as well. How often do we vaguely agree with a client just to end a call, so that you can get back later with objections after further analysis? How often do we give a non-committal smile and a nod with close relatives when our minds are preoccupied, to get them to let us off at that moment? I would say often enough for us all to recall the last time we did it. Is this any different from the example of diplomacy, where sugar coated words that are not really meant are used to get on with real business? And is this any different from training forms only to do whatever is necessary, however one can? I would say they are the same. We are all getting on with our mundane lives, in the best way that we can. If this is something we can deduce starting with the Dashāvatāra, it adds to the notion that martial concepts are embedded in the cases studies that are the stores from Hindu tradition, apart from the life lessons that are expounded upon in many books.

Notes:

*Link to Deepavali article –

***Link to the biography of Yamaoka Tesshu –

https://www.amazon.in/Sword-No-Sword-Master-Warrior-Tesshu-ebook/dp/B00GXE93CS?ref_=ast_author_dp

**The Dashāvatāra

| Sl. No. | Avatāra | Objective | Activity |

| 1 | Matsya | Protect people from the flood | Survive The Flood – only a divine fish could get the ship of refugees to safety |

| 2 | Kurma | “Support” a joint enterprise (Samudra Manthana) | Support Mount Mandāra – only a divine being with attributes of an a powerful aquatic animal could support the mountain, hence Kurma, the tortoise |

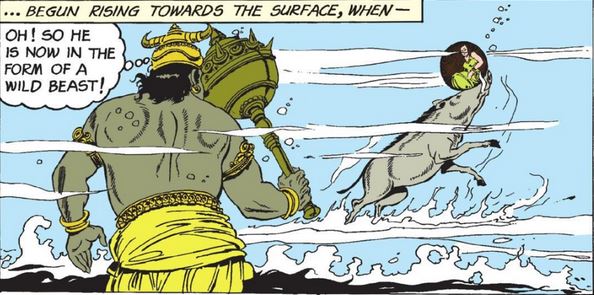

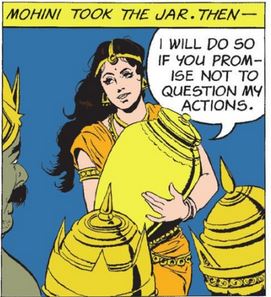

| 2a | Mohini | Protect the nectar from Asuras to protect the ecosystem | Deceive the Asuras – only an individual who was non-threatening and convincing could prevent the Aruras from starting a fight to steal the Amrita |

| 3 | Varāha | Protect the planet from the flood & people from an Asura | Eliminate Hiranyāksha – only a being that had attributes of a God, and an animal that could function in marshy areas and dig through the earth could kill him, hence Varāha (boar). I am going with the common assumption that since a boar digs through the earth, it can lift Boomi from the flood (of the cosmic ocean of milk) |

| 4 | Narasimha | Protect people from an Asura and establish peace | Eliminate Hiranykashipu – only a being that was neither man not animal could kill him (among other conditions), hence Narasimha (Man & Lion) |

| 5 | Vāmana | Protect the guardians of the ecosystem by negotiating a peace | Thwart Mahabali – only a being of divine intellect who was non-threatening could get Mahabali to negotiate and avoid violence, hence a small built brahmana, Vāmana |

| 6 | Parashurāma | Protect people from arrogant rulers, and establish the idea of violence as punishment and protection | Eliminate the arrogant Kshatriyas – only a divine Brahmana with the attributes of a warrior could single-handedly defeat the Kshatriyas |

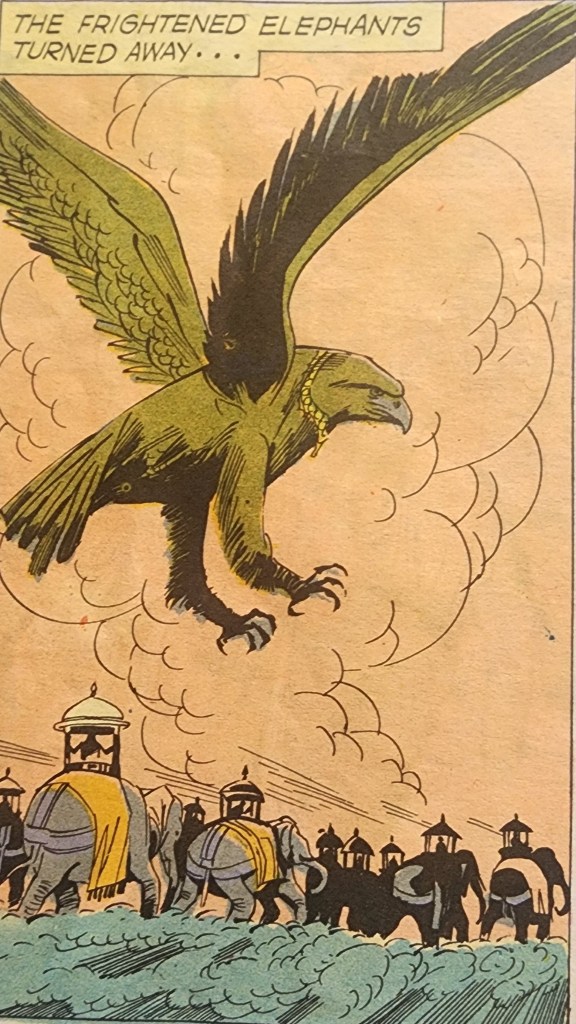

| 7 | Rāma | Establish a benchmark for administration, personal conduct and protect people from an Asura (a lifetime’s effort) | Eliminate Rāvana – only a mortal could kill him, hence Rāma |

| 8? | Balarāma | Support Krishna | I am not sure |

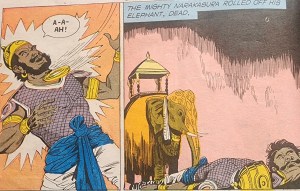

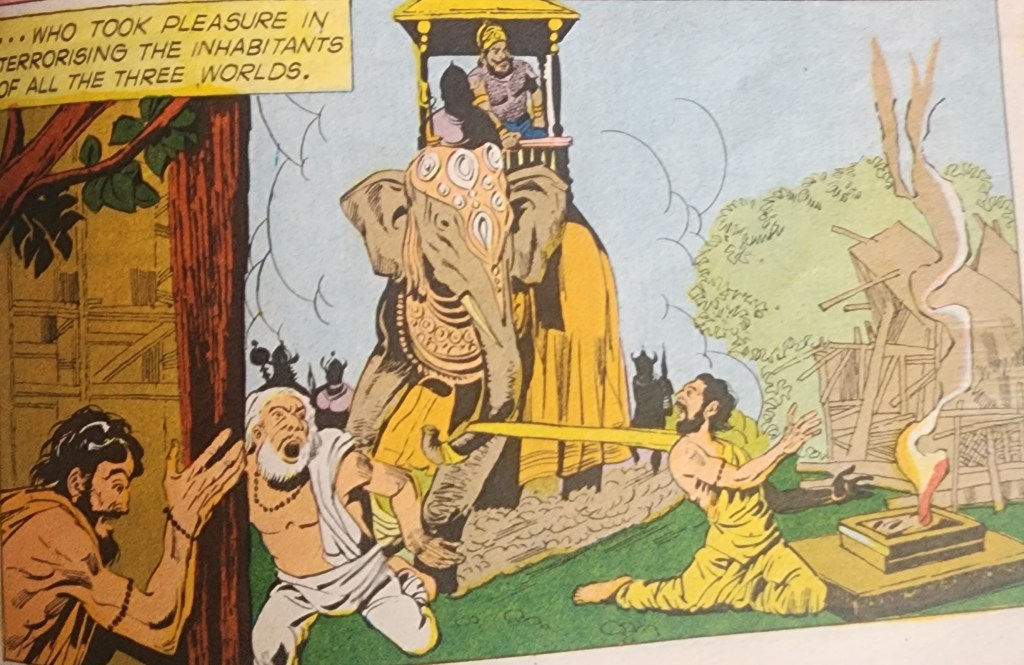

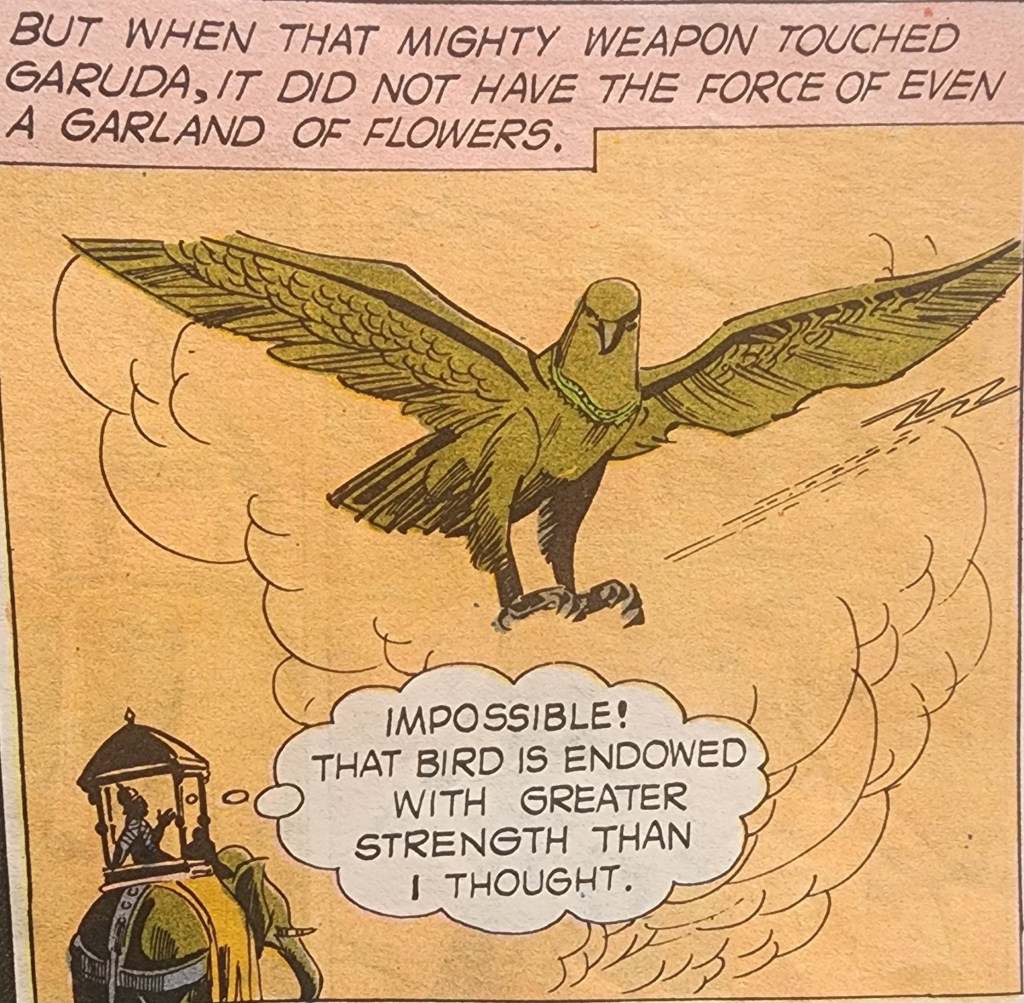

| 8 or 9 | Krishna | Establish the idea of Dharma as the foundation of administration and personal conduct, supplanting reputation (and supplementing personal conduct) – another lifetime’s worth of effort | Eliminate Jarāsandha – only a duel would result in his being eliminated without a devastating war Eliminate Narakāsura – only an aerial attack would result in his being eliminated without a devastating war Defeat Kaurava army – only a divine being could possess the abilities to guide the Pāndavas to victory All of the above were possible through a divine being not worried about honour and inclined to the objective of Dharma. |

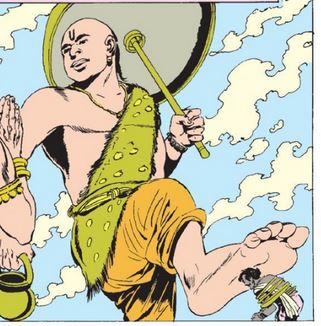

| 9? | Buddha | Initiate the idea of a limitation of ritual, a limitation of connections, limitation of violence and an abundance of personal reflection – a look at aspects internal, which is an addition to a look at all external aspects from the previous avatāras | Minimize ritual and attachments – hence an individual who had it all and renounced the same – Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha |

| 10 | Kalki | Not sure, as this is in the future. Supposed to be to protect people from bad rulers and hordes of bad people. More like a reminder of the avatārās before Buddha, for they might be forgotten in the time that has elapsed. The earlier incarnations are a perpetual activity, and they lead to conditions that allow reflections, which might lead to more Buddhas. | Yet to happen |

Mohini (L), Kalki (R)

Credit for the images – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, Kindle edition

A few other cases where specific solutions were achieved through divine births and incarnations are mentioned below.

- Lord Ayyappa – He was the son of Shiva and Vishnu (in his form as Mohini), born to end the terror of Mahishi, the sister of Mashishāsura.

- Lord Karttikeya – He was the son of Lord Shiva and Devi Parvati, who was born to end the terror of Tarakāsura.

- Devi Durga – She was a form of Devi Parvati (Shakti) who was created and armed specifically to defeat Mahishāsura

- Devi Kāli – She was a form of Devi Parvati (Shakti) who was created specifically to defeat Raktabeeja

The Goddesses mentioned above killed Asuras other the ones I have mentioned, as did Lord Karttikeya. I would highly recommend everyone to go and read the original stories. They are wonderful; not just entertaining, but also have a lot of symbolic value if one goes into the detail and serve as case studies as well.