A young Spectacled Cobra

Today, 29th January, 2025, is the Chinese New Year. This year is the “Year of the Snake”. More specifically, it is the “Year of the Wood Snake”, “wood” being the element associated with the animal of the zodiac this year. Due to historical cultural connections between China & Japan, we use the zodiac animal associated with the year as inspiration for training, every now and then, in the Bujinkan (which is of Japanese origin). This is not a norm, but something that is not uncommon either. Snakes are animals that have a strong presence in Hindu culture. So, me being a Hindu, a Budoka, and someone who has a deep respect for snakes, inspired me to write this article.

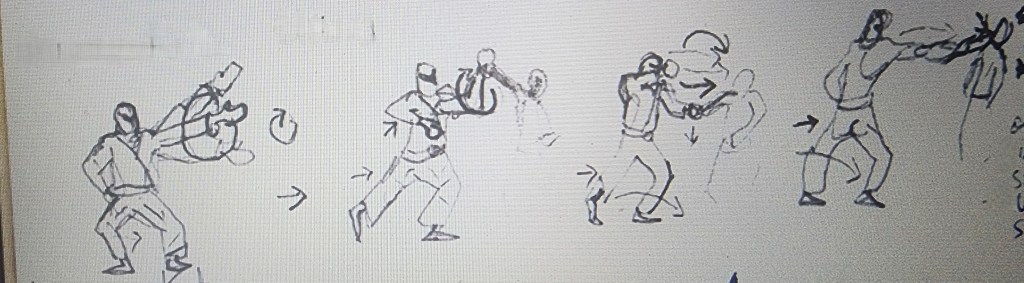

Everyone knows of the main aspects that are considered advantages in the martial arts. These generally are strength, speed and agility. Skill and experience can offset some of these. But weapons mitigate the advantage physical prowess provides. This includes both offensive and defensive weapons. In my previous post, from last week, I had discussed the importance of weapons in the martial arts*. This seems like a nice follow-up. One advantage that weapons additionally provide is reach, or how far away an attack can be carried out. Modern weapons of course also have “range” which is how large an area can be affected (of course, “range” can also be used interchangeably with “reach”, when it comes to modern weapons).

While training the Bujinkan system of martial arts, one story that everyone learns is that of Ishikawa Goemon. Ishikawa Goemon is a legendary character from the Sengoku Jidai (warring states period) of Japan, which is the second half of the 16th century. Ishikawa Goemon is a shinobi from Iga who tries to assassinate either Oda Nobunaga or Hideyoshi Toyotomi, using poison. I have been told that there are stories which describe him as trying to assassinate one or the other, though neither of them are supposedly strictly historical. In both stories, the attempted assassination fails. Goemon is supposed to have been executed along with his family according to some tales while some supposedly say that he escaped.

Chains that guide rain water into a harvesting area – something like Goemon used to guide poison into his quarry’s mouth?

Despite the failure of the attempt, the means he used in the assassination is fascinating! He gained access to the bed chamber of his target and hid in the rafters overhead. When the quarry was asleep, he let poison drip into the mouth of the sleeping individual over a thin rope. Think of this as the chains used to guide water into a harvesting tank below. The poison only made the target sick but was insufficient to kill the person. This legend was used in a sequence in the James Bond movie “You Live Only Twice” starring Sean Connery.

Another story related to “Ninja” using poison is something I saw in the old Discovery Channel series “Ancient Warriors”. This series showed how various groups of historical warriors fought and lived. This series ran between 1994 and 1995. One episode of this series focused on the Ninja and was titled, “The Ninja: Warrior of the Night”! This series has not aged well. The “facts” shown in the series are questioned and not considered entirely accurate.

In this episode about the “Ninja” a situation is narrated where the ninja assassinate a warlord by sprinkling poison powder on flowers in his garden. The ninjas observe that the warlord takes a stroll in his garden every morning smelling the flowers. They use this behaviour of his to kill him. Even in the episode, the name of the warlord is not mentioned, nor is any context given for the assassination. So, I am not sure if this is historical, and if it is just a story, I would request anyone else who might have heard the same, of its antecedents. Who is being referred to in the story and in what quasi-historical situation? I am attaching a link to a video of this episode in the notes below**.

Irrespective of the provenance of the second story, the two stories mentioned above show that the use of poison is certainly attributed to Shinobi. And this links the Shinobi/Ninja to snakes. Many creatures on our planet have developed “Venom” as a survival strategy. These include molluscs (e.g. snails), arthropods (e.g. scorpions), insects (e.g. wasps), amphibians (e.g. frogs) and reptiles (snakes and lizards). But snakes are undoubtedly “top of mind” when it comes to creatures that use chemical weaponry, namely venom (many a time referred to as “poison’).

An old photo of a Saw Scaled Viper

A small tangent here. Venom is poisonous. I have heard a beautiful explanation regarding when the terms venom and poison should be used. I will repeat the same here. If a snake bites a person and the person dies, the snake is VENOMOUS. If a person bites a snake and the person dies, the snake is POISONOUS. In contrast, if a snake bites a person and the snake dies, the person is POISONOUS. If a person bites a snake and the snake dies, the person is VENOMOUS.

This is why there exist frogs referred to as “Arrow Poison Frogs”. These frogs secrete a venom from their skin. So, if any animal bites these frogs or tries to eat them, the frog is POISONOUS and hence they learn to not consider the frog food. Similarly, there are “poisonous” mushrooms, which if eaten, can kill the individuals who eat them. Now, we go back to the main article.

One of the things that a practitioner of the Bujinkan system learns in the first few months of training is the “Hi Ken Juroppo”. This refers to the 16 ways of striking/hitting an opponent, without weapons. This includes the use of the fists, fingers, elbows, knees, feet etc. Apart from this, a concept called “Shizen Ken” is taught. Shizen Ken can be translated as “natural weapons”. This generally refers to nails, teeth and spit in humans. In other words, one can scratch or bite or spit at opponents. These are not trained as a part of “striking” an opponent as these are considered to be more “natural” or something we do due to our evolutionary past.

When it comes to animals, shizen ken would be horns, claws, fangs, tongues (think chameleons), beaks, and of course, VENOM. Obviously, when we consider weapons, we need to consider defensive weaponry as well, the examples mentioned earlier being exclusively offensive in nature.

Defensive weapons in animals include armours (carapace, cuticle, shell ec) in the case of crocodiles, tortoises and crabs, secretions (like the ink used by squids and octopi and the stink raised by skunks), spikes in porcupines and of course the wide range of camouflage that exists in nature. Beyond these, we can include the warning mechanisms used by animals under shizen ken. This includes the warning sounds used by various animals and the bright display colours that poisonous animals like frogs and caterpillars sport.

If we consider protection developed by various creatures against the heat, cold and the natural elements, this list of “natural weaponry” deployed by life on earth increases manifold! Of course, the development of weaponry is not limited to the animal kingdom. Weapons, mainly defensive ones are seen even in the plant kingdom, like thorns, resins, hard shells and of course poison.

Considering just snakes, they have developed a natural weapon that gives them a huge advantage in the battle for survival. Venomous snakes are distributed all across the world, but not all snakes are venomous. Venom is one of the weapons that snakes have evolved apart from size, speed, camouflage, agility and flexibility, which are seen in many species of snakes, sometimes in conjunction with venom.

An old photo of a young Common Krait. I could be mistaken here, this could be a Wolf Snake, which looks very similar to a Common Krait.

One factor about weapons is that they nullify the advantage proffered by size and strength. This is true in all species. This means that venomous snakes can afford to evolutionarily be smaller in comparison to many other snakes. This also means that they can be ambush hunters and minimize the risk they face from prey, struggling or otherwise. Of course, nature being nature, not all venomous snakes are small. Some rattlers and bushmasters in the Americas grow pretty large. Gaboon Vipers in Africa are large as well, and then there is the King Cobra, which is a very big snake by all standards, by length if not weight and girth. But most venomous snakes can be small or medium sized. In India, the Saw Scaled Viper, the Common Krait and many of the Pit Vipers tend to be on the smaller side according to common parlance. Cobras and Russel’s Vipers are medium sized snakes.

A majestic King Cobra

I have seen on some nature documentaries, the afore mentioned African Gaboon Vipers described as “docile”. This is in relation to its behaviour vis-à-vis humans. Of course, every snake has a different temperament and this is only a general characterization that I have heard. I am not even sure if this observation is correct. But assuming what I have seen is correct, I make the following observation. The Gaboon Viper has very large fangs to deliver venom, the largest of any extant snake. It can deliver a large dose of venom in a single bite. So, if I anthropomorphize the Gaboon Viper, it is so certain of its natural abilities and of course weapons, it has no need for any aggression. It knows its opponents will stay away due to fear or evolutionary knowledge of its weapons. Thus, it can AFFORD to be docile!

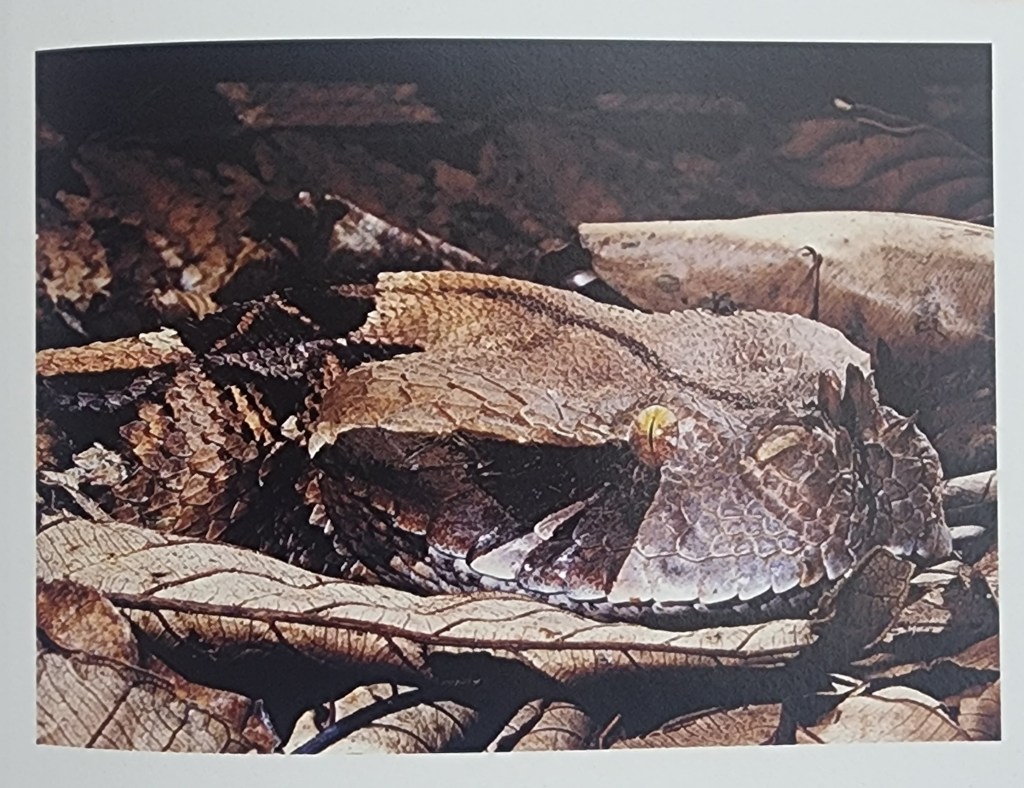

The Gaboon Viper also has a fantastic camouflage pattern that resembles the leaf litter on a forest floor. Lastly, it is an ambush hunter. Now consider the following traits. The Gaboon Viper can inject sufficient venom to kill its prey in a single bite – it is therefore armed with lethal weapons. Due to its camouflage, its quarry cannot see it coming. Being an ambush hunter, it can lie in wait for long durations. Consider these traits together – it is literally an Ishikawa Goemon from another species! Of course, there are several other snakes that have the same combination of traits and I am just using this as an example.

A Gaboon Viper amidst leaf litter. Image credit – “1000 Wonders of Nature”, published by Reader’s Digest

In India, in the stories from Hindu culture, there are entities called the “Nagas”. Nagas are depicted as part human and part snake in many representations. They are also depicted exactly as snakes in others. I have heard some people distinguish between Nagas and snakes. Snakes are also referred to as “sarpa” in many Indian languages. Some people suggest that Nagas are different from “sarpa” or snakes since they have traits that far exceed those of snakes, traits that far exceed those of humans as well. But the Nagas are definitely linked to snakes and in modern Indian culture, the difference is hardly ever considered. Nagas are also prevalent is South-East Asian culture.

A representation of a Naga as depicted in South East Asia

The Nagas, based on my knowledge have three traits that most Hindus are commonly aware of.

- Firstly, they are symbolic of fertility, in humans and of the land itself.

- Secondly, Nagas and snakes in general, are considered guardians. They are depicted as guardians of material wealth, like ancient and hidden treasure. They are also symbolic of wisdom and spiritual prowess.

- Lastly, Nagas are considered technologically superior as cultures go, which is perhaps an offshoot of their being associated with wisdom.

I will share a couple of examples of this technological superiority. In the Mahabharata, during the Ashwamedha Yajna after the Kurukshetra War, Arjuna is killed by own son Babruvāhana. He is healed and brought back to life by his wife Uloopi, who is a Naga princess. Uloopi uses a “Naga Mani” to heal Arjuna. The “Naga Mani” is a popular trope in modern Indian entertainment as well. It again links treasure (Mani is a gemstone) with the Nagas. This story shows Nagas possessing technology or knowledge that allows them to perform tasks that are beyond normal humans. It brings them closer to the divinities in this sense.

Uloopi summoning the “Naga Mani” or the Gem of the Nagas. Image credit – “Uloopi”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

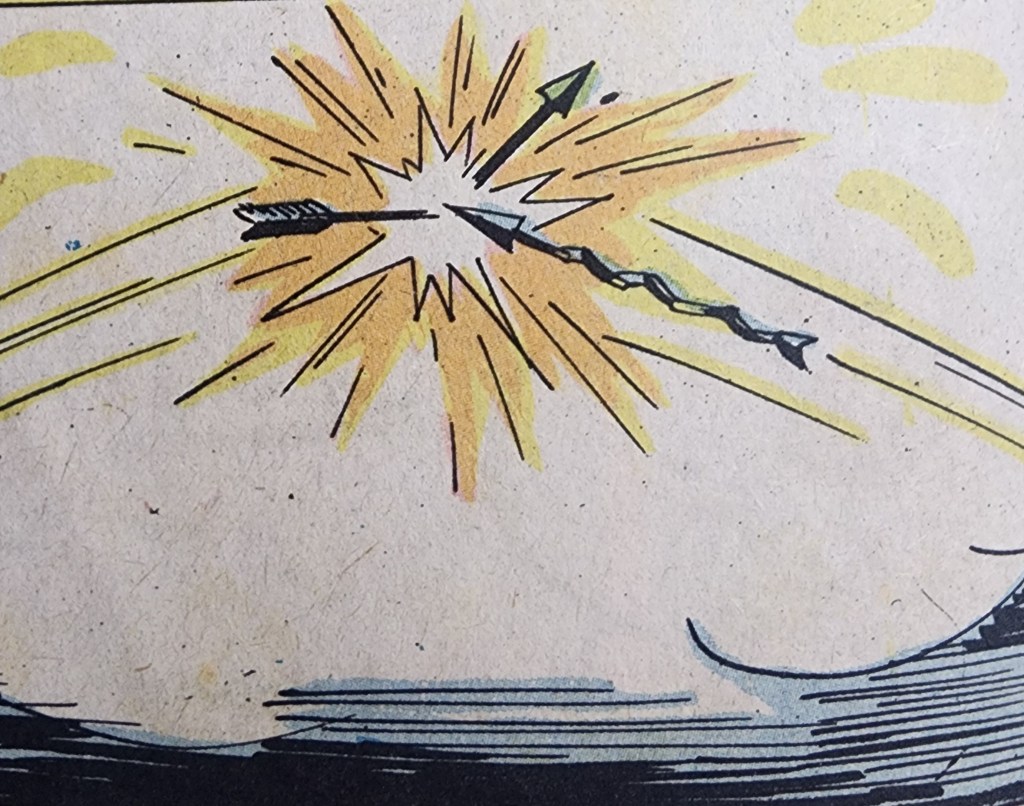

The other example is the “Sarpāstra” or the “Nagāstra”. “Astra” can be translated as an arrow or a projectile weapon. Astra can be used to depict any weapon that is discharged, with a bow or any other device (the air-to-air missile developed by India for its fighter aircraft is also called “Astra”). This is a special arrow used in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharta. This arrow is supposed to never miss, unlike other arrows. Further, an adversary who is struck by this arrow is either sure to die, with no hope of recovery, or be bound for all time, as one can never escape the weapon’s clutches. In essence, this Naga weapon is more capable compared to those used by humans.

A representation of the “Sarpastra” being superior to a normal human arrow. Image credit – “Uloopi”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

These positive traits associated with Nagas results in names associated with Nagas being widely prevalent in India even today! Names like “Nagaraj”, “Nagaswamy”, Nageshwar (male version) and Nageshwari (female version) and many others associated with Nagas are encountered by all of us regularly. All of these names translate to “King / Lord/ Chief” of the Nagas. I am sure all of us can recall at least one friend or relative who has a name associated with the Nagas. This is not to mean that snakes are not feared in modern India. There is a healthy respect for snakes all across India. The association with the Nagas, and hence snakes, is not new. Many royal lines from the times of Ramayana and Mahabharata to historical times link themselves to Naga ancestry.

It might seem that Nagas, who are part of legend and folklore in India are the ones who have positive traits. It is not snakes that have positive traits. I beg to differ on this point. I will share my personal opinion on this point. Let us begin with venom again. Earlier, I mentioned the astra named after snakes or Nagas. This is literally true in snakes! Snakes have developed the mechanism to deliver venom at a “stand-off” distance. There are multiple species of Spitting Cobras that have evolved a fang with an opening through which they can spray venom on an adversary, and keep them at bay. This is a true astra indeed!

Let us now consider aspects of snakes beyond the use of venom. Let us begin with the physical trait of snakes that everyone recognizes – the forked tongue that snakes possess and flick in and out of their mouth every now and then. Snakes use their tongue to analyse the environment around them. Snakes have an organ on the roof of their mouths, on the inside, called the “Jacobson’s Organ”. The tongue collects samples from the air and deposits it onto the Jacobson’s Organ, which in turn determines what the surrounding atmosphere is like. This is like snakes carrying around a lab inside their heads that can analyse their surroundings! This is miniature technology like no other!

The forked tongue of a snake

Of course, this is not limited to snakes. Other species have evolutionary senses that seem like magic, or at least marvels of technology, thanks to modern science. Some raptors (birds of prey) can see in the ultraviolet spectrum, sharks can detect the electrical signals in water to find food and elephants can communicate using infra sound. These are just a few examples from the natural world, without even considering the plant kingdom.

Considering evolutionary senses, one cannot ignore “the Pit” used by snakes. Pit vipers and some pythons have an organ called the “Pit” at the top of their heads on the outside. This pit is a sensory organ that allows the snakes that possess them to perceive their surroundings through something like “heat vision”. They can identify temperature differences to identify prey and track them.

So, considering just the two examples above, snakes carry in their heads, heat vision equipment and a lab to study their surroundings! 😛 This does indeed seem like high technology to us humans, in hindsight of course. Therefore, Nagas, who are linked to snakes and sometimes are nothing more than anthropomorphized forms of snakes, are no doubt considered wise and technologically advanced.

Nagas represented as part human and part snake. Image credit – “Uloopi”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

Even if one considers humans before modern science revealed all the “super senses” that snakes possess, we can still explain the fascination with snakes. In a previous article of mine***, titled “Ashta Siddhi and Budo”, I had discussed what are considered the “8 achievements” of a warrior and how they can be understood through modern budo practice. The fifth of these five achievements is called “Praapti”.

“Praapti” can be considered to be “able to receive everything”. This in modern parlance, in my opinion, refers to being able to perceive all the information in a given time and space, which in turn aids in conflict management and hopefully conflict mitigation. For practitioners of the Bujinkan, this would, again in my opinion, be nothing other than “Sakkijutsu”. Sakkijutsu, put simply, is one’s intuitive ability, which could also be termed as “awareness”, “situational awareness” or “mindfulness”.

The sensory abilities of snakes described earlier would be apparent to people in historical times, for they were keen observers of the natural world as well. The senses of snakes might not have been explained, but it would not be something unknown either. So, in a culture where, the ability to perceive the surroundings is celebrated as one of the “8 achievements” and the ability of snakes would be known, would snakes and therefore the Nagas, not be deeply respected as well? I would say that they definitely would be.

All of the above aspects I have mentioned are beyond the usual symbolism attached to snakes – that of growth. The act of moulting has made snakes a symbol of “growth” and therefore “transcendence”. The points shared above are from the perspective of a Hindu in modern India, who is also a practitioner of the Bujinkan (an expression of Budo).

I had started this post with a couple of quasi historical stories from Japanese history. I will now revert to Japan to make yet another point. During my training the Bujinkan, I have learnt from a mentor of ours, Arnaud Cousergue, that the Togakure Ryu, one of the schools of Ninpo Taijutsu (sometimes referred to as Ninjutsu) that we learn, is divided into 18 segments. Only a few of these 18 segments are trained in dojos these days. One of these 18 segments is “Kayaka Jutusu”. This refers to training the use of explosives. There is no segment that is attributed to the practice and use of poisons. But Ninjas did use poison as evidenced by the two stories mentioned earlier. So, could it be that a segment for poisons was not present in just the Togakure Ryu? Or was it subsumed under “unconventional weapons”, the chief of which was gunpowder and explosives in later centuries? I am not a historian and have no answer to this question.

In my personal opinion, this segment, “Kayaka Jutsu”, could perhaps be considered to refer to the use of unconventional weapons. A theory about the origin of the Togakure Ryu states that it originates in the 12th century. This was before Japan’s first encounter with gunpowder and explosives, which was during the Mongol invasion, in the late 13th century. So, maybe this segment among the 18 was added later during the evolution of the Togakure Ryu? Or, as mentioned earlier, was it that this segment referred to “unconventional weapons” in general and later became specific to explosives as that was the primary new weapon? I am assuming it was so. If anyone knows otherwise, please do share your knowledge with me.

While considering “unconventional weapons”, there is one trait of snakes that is truly staggering, the very definition of “unconventional”. Snakes have no ears and do not hear like other animals. Snakes sense vibrations through the bones in their head. But their “hearing” or perception of sound in comparison to humans and other animals is poor. But snakes use sound to warn potential threats.

Russel’s Viper

The best example of this are rattle snakes. They have evolved a rattle to warn creatures who intrude on their habitats. Similarly, in India, if anyone has heard the warning hiss of a Russel’s Viper, it sounds like a pressure cooker about to go off! In both these cases, sound is used as a warning device. This means that snakes use a medium of perception to warn creatures, that they themselves do not possess! Snakes cannot hear but know other creatures can! And they use that sense for the benefit of both! How cool is that! It is baffling and “unconventional” to say the least.

Of course, the ability to use a medium one cannot perceive well is a product of evolution over millions of years. And evolution itself brings to mind two aspects that are expressed in the Bujinkan. These are Kami Waza and the fourth of the Gojo, “Shizen no choetsu”.

Kami Waza is a concept where one moves during a fight in such an amazing manner that it seems like one was being moved by something divine. This is exactly what evolution is! The outcome of evolution seems truly magical in hindsight. I had referred to Kami Waza in my article about the Ashta Siddhi, which is linked here. “Shizen no choetsu” could be translated as “the transcendence of nature”. It is the fourth of the 5 Gojo that is oft quoted in Bujinkan dojos. I had written an article some time ago where I have discussed my understanding of the five Gojo. The same is linked here+.

Evolution that is seen in nature is about continuous and incremental changes to overcome challenges in ways that are inconceivable at any given time. The ability of a creature that does not use sound to ward off creatures that do use it, without knowing the experience of sound is exactly that! Transcendence in its essence! First an animal realizes that other animals perceive something that it does not, and then devices a means to use that perception to its advantage, but without developing that perception in itself! 😀 I know, I am saying this a lot, because it boggles the mind!

There is another Gojo, the third of the five that goes, “Shizen no Ninniku”. This can be translated as “the forbearance of nature”. This refers to how one needs to persevere through any activity, just like nature has an abundance of ability to take any challenge and over time overcome the same. I have discussed this also in my previous article. I will use a personal experience of mine to show this trait in snakes.

My family used to run a rescue and rehabilitation centre for wild animals within the city many years ago. This centre functioned from the late 1970s through the late 2000s. Sometime in the late 90s of the early 2000s, an interesting incident took place. We got a call from a local timber yard about a snake in one of the logs at their premises. It was a log that had been transported from Malaysia to India. In the log was a clutch of eggs that had not been noticed earlier and had somehow survived the processing of the tree before transportation.

One of the eggs hatched and a live Small Banded Kukri Snake emerged from the same. It was a Malaysian species of Kukri Snake which hatched in India. Unfortunately the snake did not survive long. But this does show how snakes can survive and extend their territories. In this case an egg travelled from Malaysia to India and hatched. We hear many stories of how Burmese Pythons have successfully created a habitat for themselves in Florida, the other side of the ocean.

A large Indian Rock Python

Snakes can endure habitat destruction, disturbances to their nests and dwellings, human trade in exotic pets and still find new habitats to inhabit. This is a wonderful example of how nature perseveres, its forbearance is infinite. This is not unlike how one needs to spend years to train the martial arts. It is a gradual process, demanding time, effort and many resources to be expended.

That is a roundup of the fascinating connections between snakes, the martial arts and Indian culture. In conclusion, snakes are like a living breathing sensor package, much like modern day fighter aircraft and other weapons systems. This is like “Praapti” in Hindu culture and Sakkijutsu in the Bujinkan. This is also the key behind modern day 5th generation warfare, where conflicts are not kinetic and information gathering is of paramount importance and technology is a vital ingredient. Technology of a natural kind is what snakes also deploy, chemical weaponry, or venom, in a world where strength, speed and size matter. This leads back to the martial arts, where unarmed combat might be basic, but weapons are the true expression of the art. And we have not even spoken about flying snakes or the world of the sea snakes…

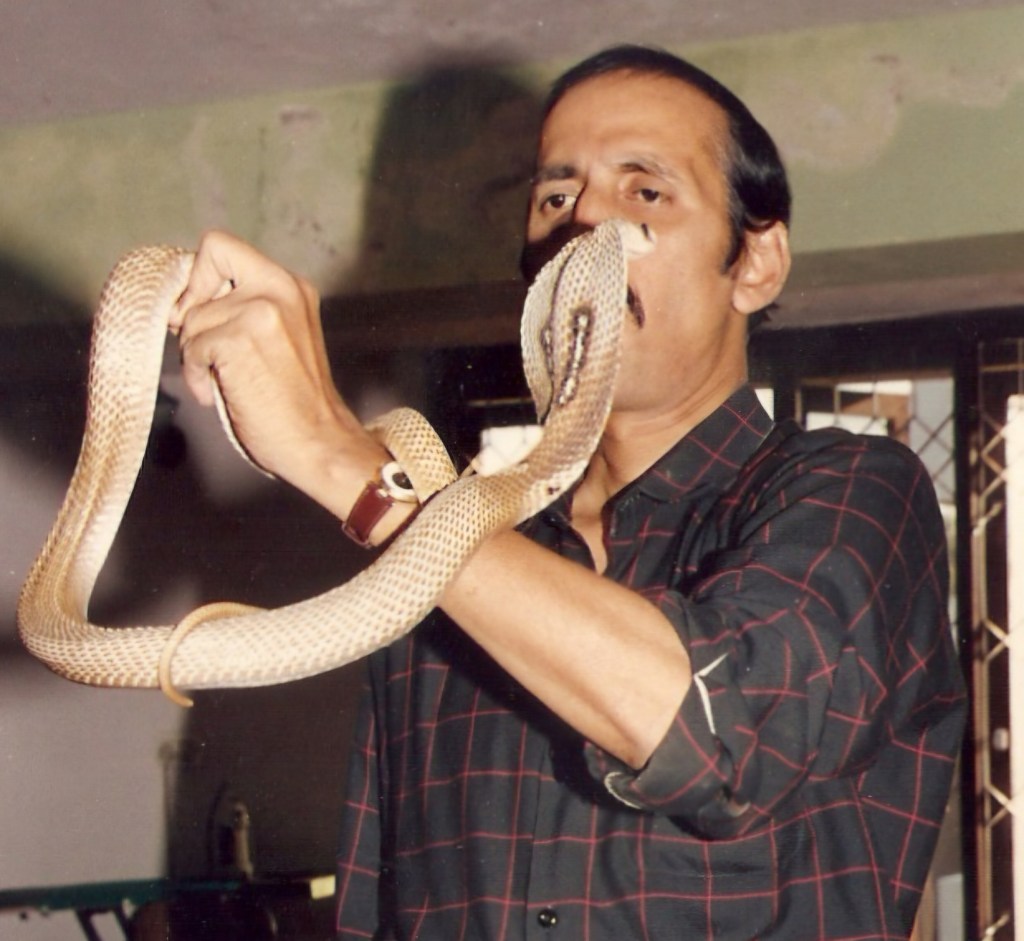

Acknowledgements – All images unless mentioned, were taken over the course of many years by various members of my family. I share my deep gratitude to my uncle, Dr. Shashidhar for sharing many images of the many creatures that shared our home over the decades.

This post would be incomplete without sharing a couple of images of another uncle of mine, the late Srinath. He had an innate understanding of all wild creatures and a knack for working with snakes that was, to say the least, intuitive. He could sense the temperament of any snake, or any animal for that matter, in an instant. Watching him work with wildlife will be something that I will never not miss!

Left – With a King Cobra. Right – With a Spectacled Cobra.

Notes:

* https://mundanebudo.com/2025/01/23/the-bujinkan-as-i-see-it-series-1-part-4/

** https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6ch45c – watch between the 10 and 12 minute mark

*** https://mundanebudo.com/2022/12/22/the-ashta-siddhi-and-budo/

+https://mundanebudo.com/2023/03/16/the-gojo-a-personal-understanding/