Today, 19th Feb, is Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Jayanti or the birth anniversary of Shivaji Maharaj. Shivaji Maharaj, who lived between 1630 and 1680, was the founder of the Maratha Empire (later Confederacy) that grew to be the most powerful political and military entity in India in the 18th century. He is also an extremely influential historical and cultural icon in modern India.

Portrait of Shivaji Maharaj. Image credit – Wikipedia

Shivaji Maharaj is an icon because of his military, political and social achievements. There are several books, series and movies featuring his life. His life is filled with several instances of derring-do, each of which, if not known history, would seem like the imagination of a great script writer. Shivaji and many of his military leaders were involved in acts of military heroism and greatness that are remembered to this day. Listening to the stories of their escapades is a hair raising, goose-bump inducing experience to this day, simply because these were audacious and carried out against overwhelming odds. Some of these would perhaps be called “Special Forces” operations if they had occurred in contemporary times.

Listed below are some of the incredible victories of Shivaji Maharaj and his military leaders in the second half of the 17th century. These are the ones that are top of mind for me, not a comprehensive listing.

- The Battle of Pratapgarh, Nov 1659 – Shivaji Maharaj killed Afzal Khan with his Bagh Nakh during this conflict.

- The Battle of Pavankhind (Ghodkhind) July 1660 – Maratha General Baji Prabhu Deshpande with 300 troops held back a Bijapur army many times its own size in a narrow pass allowing Shivaji Maharaj to escape.

- Battle of Surat, Jan 1664 – Shivaji Maharaj led a daring night attack against much larger Mughal forces led by Shaista Khan.

- Escape from Agra, Aug 1666 – Shivaji Maharaj and his son Sambhaji were political prisoners in Agra. They escaped through stealth, without a military action.

- Battle of Singhagad (Kondhana)*, Feb 1670 – Maratha General Tanhaji Malusare and his troops scaled the walls of the Kondhana fort to defeat Mughal forces in a surprise attack.

- Capture of Panhala fort, 1673 – Maratha commander Kondaji Farzand is supposed to have captured the fortress of Panhala with just 60 men, defeating a garrison of 2500 men (I am not aware if this is confirmed history of if folklore is mixed with history).

- Battle of Umrani, 1674– Maratha General Prataprao Gujar led Maratha troops to victory against the army of the Bijapur Sultanate. There is a story relating to this battle where 7 Maratha warriors attacked the enemy camp, losing their lives in the process, but leading to an eventual Maratha victory.

- Southern conquest – Shivaji Maharaj embarked on a conquest of many parts of Southern India between 1674 and 1680. This was in the direction opposite to that of their primary threat, the Mughal Empire under Aurangzeb! This military action later allowed the Marathas to survive the 26 year long Mughal-Maratha war.

- Bahirji Naik – He was supposed to the spy master for Shivaji Maharaj, who was instrumental is several successful military campaigns. I am not aware of the full details of his specific role in the many military actions of the then fledgling Maratha Kingdom (it became an Empire later).

- Maratha navy – The Marathas built a coastal navy which for many decades was a match for the Siddis of Janjira and all the European navies operating off the Indian coast at that time.

Consider the first battle mentioned above, the Battle of Pratapgarh. This occurred in late 1659 between the army of the Adil Shashi Sultanate of Bijapur and the Maratha Army. The Adil Shashi army was led by Afzal Khan and the Marathas were led by Shivaji. Afzal Khan was supposed to have been a giant of a man, standing somewhere between 6’6” and 7’ tall, and suitably large as well. Shivaji was supposed to have been about 5’6”.

This is a representation of the size disparity that was likely between Afzal Khan and Shivaji Maharaj!

The Marathas could not win in a pitched field battle and Afzal Khan’s troops could not face the Marathas in the hills and jungles. So, there was a siege of sorts of the Pratapgarh fort. A parley was arranged to allow for negotiation and perhaps a surrender of the Marathas without bloodshed. Afzal Khan and Shivaji were supposed to meet without any weapons and one bodyguard each to parley.

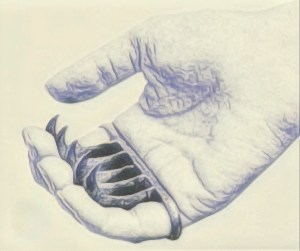

They are supposed to have met in a tent. Afzal Khan had a dagger hidden in the robes of his garments. Shivaji Maharaj did not trust Afzal Khan and hence wore chain mail armour under his garment. Shivaji also wore a Bagh Nakh (sometimes called the Wagh Nakh). This is a small weapon that resembles the claws of a tiger and is worn on the palm. “Wagh” or “Bagh” means “tiger” and “Nakh” means “claws”. The weapon is worn through rings on the fore and little fingers. The weapon is not visible and stays hidden in the hand. An opponent in front only sees two finger rings at first glance. Images of the bagh nakh and how it was carried are seen below.

A representation of a “bagh nakh” / “wagh nakh”

When they met in the tent to parley, Afzal Khan is supposed to have invited Shivaji for an embrace as he was the son of his friend. Afzal Khan knew Shivaji’s father who was also in the service of the Bijapur Sultanate. When the two embraced, Afzal Khan is supposed to have used his massive size and strength to try and crush the much smaller Shivaji. When this failed due to the chain mail, the large man drew his dagger and attempted to stab his opponent to death. This also failed as the dagger did not penetrate the mail shirt.

In defence against this attack, Shivaji used the bagh nakh against Afzal Khan. He managed to disembowel and kill the gigantic enemy General. With their General dead, the Bijapur army was routed by the Maratha forces. With this victory, the “Bagh Nakh” has achieved eternal fame in Indian military history.

A representation of how a bagh nakh is worn

The bagh nakh is memorable to such an extent that it is today used as the nickname of the 21st Batallion of the Special Para. This is one of Special Forces units of India. The unit is referred to as the “wagh nakhs”, “Tiger’s Claws”!

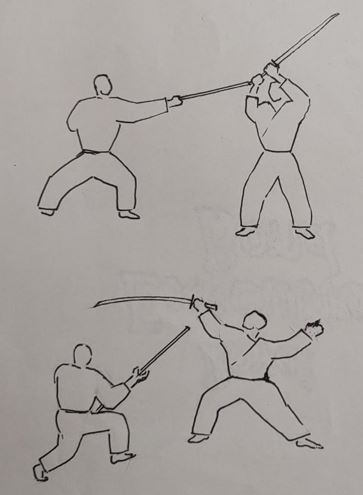

Considering my blog is about the intersection between Hindu culture, Indian history and the martial arts, here is the link between the use of the bagh nakh mentioned above and the martial arts. As my readers may know, I am a practitioner of the Bujinkan system of martial arts. The Bujinkan is a martial art of Japanese origin.

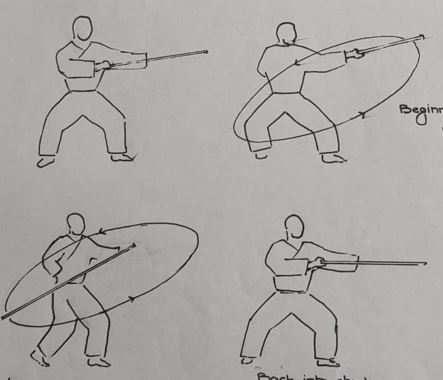

In the Bujinkan system, there is a close quarters weapon that is used, called “Shuko”. The shuko is no different from the bagh nakh. It was used historically as a tool to aid in climbing trees or scaling walls. The shuko was worn on the arms of the user and could double up as a weapon in a pinch. There is a version of the shuko that is worn on the legs, which also helps in climbing. An image of the training version of the shuko is seen below.

A representation of training version of a Shuko

The shuko can be used in grappling against an opponent wearing armour, by using the hooks or claws as points of leverage against the armour. They can also be used against unarmoured opponents to get past clothing and cause flesh wounds. In extreme situations, they can be used as protection for the palms when blocking a strike by a staff or even a sword. They are not guaranteed to protect the hand, but might improve the chances of reducing injuries. This potential use of the shuko as a weapon, shows that it is nothing but a Japanese version of the bagh nakh. Both versions of the same weapon seem to have come in handy in a really tight spot!

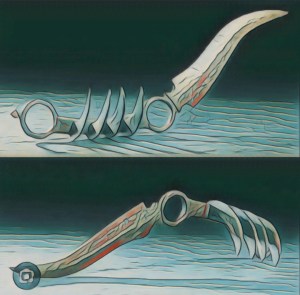

Another training version of the Shuko, with spikes instead of hooks

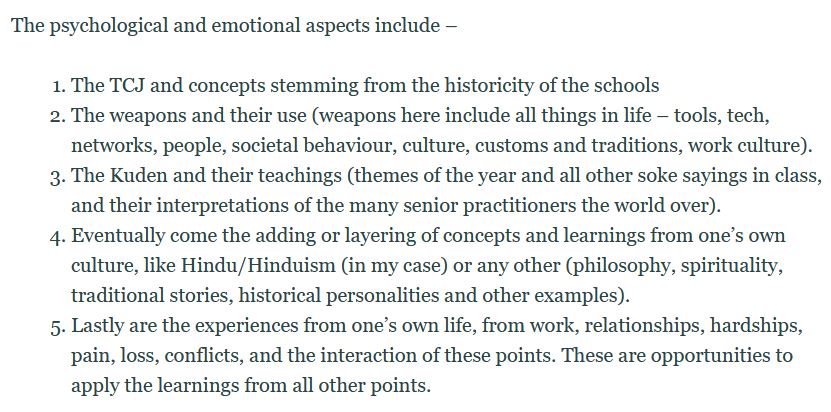

The equivalence between the bagh nakh and the shuko is the main purpose of this article, as elucidated above. But beyond this, I can see similarities in the military ways of the Marathas and the original teachings of the Bujinkan. One of the aspects taught in the Bujinkan system is “Ninpo Taijutsu”, also called “Ninjutsu”. There are 18 parts of study related to Ninjutsu, some of which include unconventional warfare.

Dr. Kacem Zoughari, a long time senior practitioner of the Bujinkan, has written a book about the history and origins of Ninjutsu, called “The Ninja, The Secret History of Ninjutsu: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan”. A link to this book is seen in the notes below. In this book, he gives many examples of how Shinobi were used in medieval times. A lot of these examples would seem like examples of sabotage and infiltration activities today.

The use of surprise raids and actions, using fire or darkness to allow small units to gain an advantage over larger forces are examples one sees in the book. This is pretty much the same thing that the Marathas employed against their more numerous opponents, who also had access to greater resources. The Marathas are always known for guerrilla warfare in the Indian mind. So, in the early stages of the formation of the Maratha Empire, their military actions were very similar to how the Shinobi operated in a roughly contemporaneous period in Japan.

I am not suggesting that either the Shinobi or the Marathas had any role in the evolution of the tactics and methods of the other. It is, in my opinion, a case of convergent evolution when faced by similar situations. But what this does reveal is that we in India have perhaps not done enough to popularize the actual combat methods of the Marathas.

The Marathas and Shivaji Maharaj are likely more popular in India than the Ninja are in Japan. But the study of the actual martial arts of historic Japan are definitely more prevalent when compared to those in India (including those of the Marathas). Yes, Mardani Khela, the martial art of the Marathas is still very popular in Maharashtra and other parts of India – but more as a performance and demonstration art. I am not sure if there are manuals of Maratha techniques that have been compiled and the same can be practiced today.

A bagh nakh integrated with a bichua (scorpion) knife

Perhaps seeing links with traditional martial arts in other countries will bring India to document her own traditional fighting arts, as more than dance, gymnastics and other performances. If traditional fighting arts can be documented elsewhere, the same can be done here, and the process might reveal a lot, like its application in other walks of life. This is perhaps as much a pranaam to Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj as is preserving his memory and legacy of patriotism and valour.

Notes –

The Ninja, The Secret History of Ninjutsu: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan – Dr. Kacem Zoughari

* A link to an older post of mine, where I discuss the attack on the fortress of Kondhana and other such forts.

https://mundanebudo.com/2023/08/15/swaraj-and-the-lizard-and-ninjas/