The murder of Hindu tourists in Kashmir earlier this week has severely affected all of us Indians. We are all coping with it in our own ways. Since I have a domain and blog, I am using them to deal with the sadness, anger and other feelings. Perhaps some of the ideas shared here might resonate with others, though that is neither necessary nor the objective of this post.

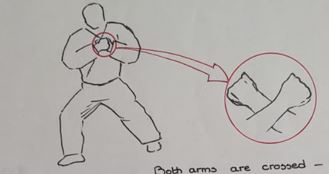

The most important thing that any practitioner of the martial arts learns is protection of the self. One can choose to use the word “defence” instead of “protection”. This is true whether one is practicing an art form that involves weapons or an unarmed fighting style. When I refer to weapons, I mean both weapons of offence and defence. Examples of weapons of defence include body armour and shields.

The emphasis on protection or defence is revealed by a very important aspect. I will use the Bujinkan system of martial arts to explain this because that is the art form I am familiar with. We are taught that even weapons of offence are first and foremost, SHIELDS. Whether one is using a sword or a spear or a staff, all weapons of offence, we are reminded that these weapons are to be used a SHIELDS before their ability to cause harm to an opponent is utilized.

When one is using a staff, or bo, the basics taught include ukemi with the staff. Ukemi refers to receiving an attack, in other words, how to protect oneself with a bo in response to an attack. This same is true while using a spear. One learns how to receive an attack and hopefully redirect it away from oneself. While using a sword, one learns how to use the strong part of the blade and the tsuba, or the disc guard on a katana to stop an attack and the middle part of a blade to control or redirect an attack – the principle is similar to how a staff or spear is expected to be used.

I must add, I am referring to traditional martial arts here, specifically to the use of shastra*, as we call weapons that are not discharged, in India. This means that the attacks I am referring to could come from swords, axes, staffs, spears and other polearms. To protect oneself, and use one’s own offensive weapons like swords or spears as shields, all one has to do is put the weapons between oneself and the weapon(s) wielded by the opponent(s).

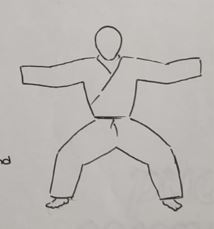

The importance of using even weapons of offence as protection is demonstrated by the concept having a posture named after it! There is a kamae called “Totoku Hyoshi no Kamae” in the Bujinkan. A kamae can mean “posture” or “attitude” (posture of the mind/spirit). “Totoku Hyoshi no Kamae” can be translated as “hiding behind the sword”. The reference to the sword is because we learnt this kamae while training the sword. But this kamae could refer to any weapon, when it could be called “hiding behind the weapon”. Simply put, this means using the weapon as a shield, by putting it between the wielder and the opponent (or opponent’s attacking weapon).

One of the senior most sensei of the Bujinkan system and soke of the Shinden Fudo Ryu is Nagato Sensei. I distinctly remember him saying, one should “Leave no opening” while facing an opponent. His statement was made with respect to how one should move in response to an attack by an opponent. He meant that when one responds, he or she should ensure that there is no opening left for the opponent to exploit. Until this is achieved, there is little sense in attempting a counter attack. Of course, this is incredibly hard to achieve and requires years of incessant training.

Another learning from Sensei’s statement is that one should keep moving in response to an attack until there are no openings left for an opponent to attack after the initial one. It need not mean that one moves or responds to the very first attack in a manner that denies any further openings. That could be a happy outcome, but not to be expected, much less depended on.

This brings us to the use of armour. One can “use any weapon as a shield” and move to “leave no opening”. The two together mean that one should move in response to an attack while using one’s own weapon as a shield. This movement will ensure that the shield is in the right place to protect its wielder. Like I said earlier, this is difficult to achieve without a lot of training and practice. Lack of training can be mitigated with the use of armour.

In any fight the conditions are always unpredictable and many a time, unknowable. In such a case, body armour is important. When the individual cannot move as required or utilize a weapon as protection, the armour takes the attack and protects its wearer. Further, armour also increases the opportunities to use a weapon of offence as it was intended, to harm the opponent.

While an armour protects the one wearing it, training is also needed to maximize the protection afforded by armour. No armour is without its openings and chinks. The openings are usually at the joints, the back of the leg and the arm pits. These openings are necessary to enable movement in armour. These openings will be targeted by opponents and practice is needed to keep these attacks at bay.

The above image shows openings in Plate Armour. Image credit – Wikipedia.

Historically, armour and weapons have evolved in response to each other. I will take the example of western armour to elucidate this. In the early Middle Ages chain-mail was worn over gambesons as armour. Later coats of plates were worn over the mail and gambeson combination. Eventually, a full plate harness came about. The full plate armour meant that the person wearing it was pretty much impervious to any weapon on the medieval battlefield. But this armour had openings as well, in the places I referred to earlier. To better protect the arm pits, chain mail was used under the plate. The elbow and knee joints eventually had articulated plates to enable movement while affording protection. The back of the legs were always vulnerable, but eventually plates were added there as well.

But weapons evolved to challenge armour. The estoc evolved from the regular sword, as a stiffer pointer version of the same. This allowed half-swording as men-at-arms and knights grappled to stab through the joints of plate armour. Daggers with reinforced points appeared to enable the same. And poleaxes evolved to combine hammers, axes and spears. The poleaxe could bludgeon opponents in armour to cause blunt force trauma and concussion like injuries. The spear point of this weapon could stab into joints and eye slits in the helmets that accompanied plate armour.

The head of a Poleaxe

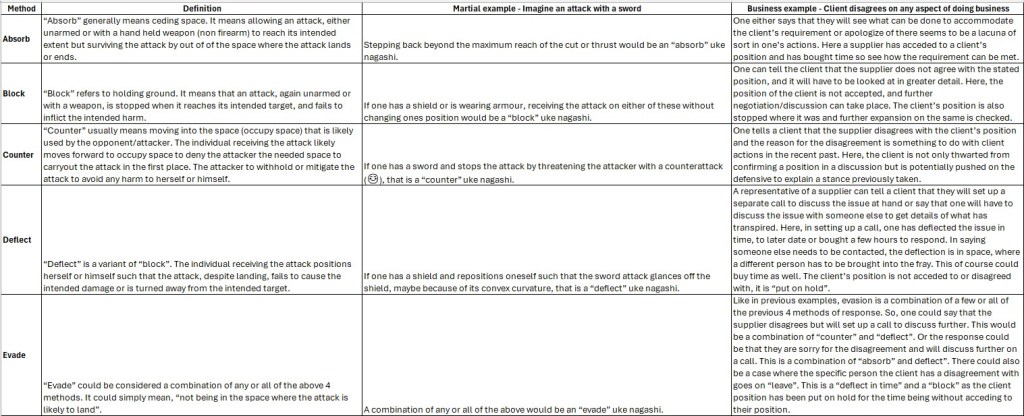

When all the previous points are considered together, the following points should be clear.

- Protection or defence is of paramount importance.

- Every armour has its openings that can be exploited.

- One needs to train to move to protect the openings.

- Even weapons of offence are first and foremost a shield for protection.

- A counter attack can only come when protection is achieved and there are no openings left for exploitation.

With the above points in mind, let me look at the situation we Indians and the Indian Government are in, post the terrorist attack in Pahalgam in Kashmir. Before I start, I must mention that I am not an expert in geopolitics or geo-strategy. I am not a defence expert or an ex-soldier. Nor am greatly aware of how international relations and diplomats work. I am just a layman, with experience in martial arts, the knowledge of which drives some of my thinking. I am as sad and angry as most of my fellow Indians and its diaspora. This post, specifically what comes next, could be considered my rant, or a means of venting; either way, it is me trying to make sense of what is going on and what could come next. When I say what comes next, I do not mean a response by India to the terrorism it has been subjected to, I mean how we Indians share opinions and react to what the administration does, or has done.

There are many people who are wondering why there was no security in the Baisaran valley in Pahalgam where 26 Hindu tourists were murdered by terrorists. That is a fair question and the government has admitted there was a lapse. Over the last 6 years tourist numbers in Kashmir were continuously on the rise and violence was on a steep decline. Hence it was assumed that normalcy was pretty much back and tourists would not be targeted as that affects the local economy. One aspect of normalcy is that overt security presence is minimized. All of this seems to have been a temporary truth and hopefully normalcy will indeed return in the near future, perhaps with overt security presence. Either way, the lack of security leads to a point that has been raised even when violence was on the wane in Kashmir and in the naxal belt. I have heard this point referred to by some as “Fortress India”.

I have heard the term “Fortress India” mean two things. First is to ensure that India’s territorial integrity is inviolable. The second is to ensure that the life of every Indian is protected within the country. The second is usually in reference to protection from terrorist violence. In my opinion, this concept of Fortress India is the same as “Totoku Hyoshi no Kamae”. It means that protection is paramount. “Fortress India” refers to the country as a whole, while “Totoku Hyoshi no Kamae” refers more to the protection of an individual. Protection of the nation includes protection of its critical assets and infrastructure apart from the people and includes protection from cyber warfare and any 5th generation warfare attempts.

Once protection or defence of a nation is paramount, weapons invariably come into the picture. And like mentioned earlier, every weapon is first and foremost a shield. To demonstrate this, the first example would be the nuclear weapons possessed by some 10 countries in the world. The nuclear option has always been a deterrent, in other words a shield. Countries possess nuclear weapons to prevent other countries from causing damage beyond a “threshold” (however they define it). No one would ever dare to use one, at least as of now.

This concept of “protection” extends in a slightly different manner to modern day “stand-off” weapons. These include missiles launched from various platforms, but mostly aircraft. These can be launched from a distance far enough away to prevent the aircraft from being targeted by the air defence platforms of enemy nations. So, the range of the missile, or glide bomb, is the defence to the platform, while still being able to deploy the offensive (destructive) capability of the missile. This is the same as moving to a position to safely parry an attack from the opponent and carrying out the counter when “there is no opening” exposed to exploitation. In the case of the aircraft, the distance from the anti-aircraft weaponry is the “safe position” when there “is no opening” to attack for the air defence systems.

A shield for the nation, easy for visual representation, but very hard in reality.

The “protection” aspect extends to any air assault being able to have an electronic warfare suite, to jam the radar of incoming attack missiles. Then there is the ability to conduct network centric warfare, where an AWACS can guide a missile fired by a fighter aircraft. Or the aircraft that is using its radar can guide a missile fired by another aircraft which is part of the same mission package. All of this requires that vastly complex technologies work together precisely. And this working together or networking, requires a great deal of training. In other words, in a strike package, some aircraft are protecting the other aircraft which are carrying out the attack. So, this is the basic concept of traditional martial arts at a personal level scaled up to massive technological deployments at the scale of national armies.

And that brings me to the concept of resources, time and money. For a modern day martial arts practitioner, there is a huge cost to keeping up with the practice, even as just a hobby. The training equipment is not cheap, and time has to be set aside for the practice, both of which are hard even if one is passionate. And seeing improvements in one’s martial abilities takes time, years even, and for recognizable changes to manifest in personal and professional lives takes longer still. This same is true for the protection of nations. Vast resources are needed, and the time taken to evolve and improve technologies runs into decades. The cost to society due to defence related expenditure can be large. So, not all nations can afford technological superiority. This includes cyber warfare and war for the minds and morale of national populations.

Lastly, technological progress, just like personal ones, will see failure, and learning from the same is needed. Losses will be faced, and overcome. Who can state that nothing has changed in India’s defence architecture since the 2019 Balakot strike and the consequences of Pakistan’s Operation Swift Retort? I would say no one can. And if someone said it, they would be wrong. Longer range missiles have been inducted, better EW suites are available, software defined radios have been introduced to overcome jamming, and more improvements are on the way.

Grey zone warfare has perhaps been used (unknown gunmen) as well. Have there been improvements in intelligence and cyber warfare capabilities? I have no idea. And improvements are happening at an impressive pace in the development of laser weapons and scramjet engines. Both of these bring us closer to an Indian version of the Israeli “Iron dome” missile defence. Just so we do not forget, there is already a ballistic missile defence shield based on the Prithvi missile. This has been deployed for a few years now. So, development is happening incrementally and continuously.

But this is not to say that there is no scope for improvement and there are certain projects that are more cause for disappointment among the general public than the rest (think Kaveri engine and the infrastructure needed for its testing). And speaking of disappointment, we come to the war being waged against the fabric of Indian society.

We are a polarized country, just like the rest of the democratic world. Homogenous non-democracies will always attempt to exploit fissures in our societal fabric, like the fault lines of caste, religion and militant leftist ideologies. This is no different than finding an opening in armour. A united national populace is armour for a nation, and the splintering of the same if the creation of an opening to attack.

This begs the question, are we protected against “narrative warfare”. It seems we are, at least for now. And are we using it successfully against adversaries? I do not know. Perhaps we are and I do not know, or maybe we are not very successful at it, yet.

This leads to the question, are we citizens responsible for protecting our own selves and hopefully each other in this narrative assault? Perhaps we are. And if yes, how successful have we been? Considering how polarized and tribal we are in current times with social media access, perhaps we are successful in not being defeated by narrative, but not successful is ensuring the opponents of the nation realize that the attack will always fail, for certain. It seems that foreign adversaries still see opportunities for success here. There is sufficient friction in the country to enable these attacks.

There is an old Bedouin saying, which goes, “I against my brother, my brother and I against our cousin, my brother and our cousin against the neighbours, all of us against the foreigner.” I suppose in the Indian context, considering the size of our population, we can expand it to something like this.

“Me against by brother or sister. My sibling and I against the family. My family and I against the village or city. My city and I against the country. My country and I against the enemy nation.”

The spirit of this saying is that no matter our differences, we unite against a threat to the nation, be it foreign or domestic. We perhaps need to train how to protect each other in the narrative wars to come.

With that I conclude this post. This article is more of a coping mechanism for me, venting if you will, as I confessed earlier. So, I do not have a clear conclusion. Just a bunch of thoughts and connections I have strung together.

Notes:

* Shastra (weapons that are not discharged), not Shaastra or Shāstra (fields of knowledge/study)