Wendy Doniger has said that the “Arthashāstra”, written by Kautilya (Chanakya) is a “wicked” book. She means this with a negative connotation, as the book recommends violence. She refers to the Arthashāstra’s recommendation to wage war with neighbours and maintain friendly relations with states that are not immediate neighbours.

I agree with Wendy Doniger. The Arthashāstra is a “wicked” book. But I mean it with a positive connation. The book is “Wicked Good”! And for the same reason that Doniger gives. It does not shy away from military conflict. It advocates readiness to participate in violent conflict, if the situation so demands.

Watch between the 48 and 52 minute marks. Between the 40 and 48 minute marks Ms. Doniger expresses her opinion on how Hinduism is a violent religion.

India is a secular nation. But it has a strong Hindu civilizational character that pervades a very large part of its population. Hindu culture is NOT inherently NON-VIOLENT. The worldwide popularity of Mahatma Gandhi* and his pervasive impact on our national consciousness might make some think that Hindu culture is “non-violent”. But it definitely is not, and it most certainly is not a believer in pacifism!

Hindu culture emphasizes “ahimsa”, but that is not the same as non-violence. I have written previously about “ahimsa” from a martial perspective. I will not repeat that here but will leave links to the earlier articles*. Simply put, ahimsa is about not having malice towards anyone or any nation. But that only means that one should not go looking for a fight. If someone brings a fight to you, the threat must be nullified, there can be no doubts there.

Jainism is closer to non-violence, since it tries to avoid harming any creature. But there were kings who practiced Jainism who did participate in wars. So, even Jainism is not entirely free from practitioners who had to commit violence. The other socio-religious systems in India, including Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and tribal belief systems (these are Hindu adjacent), did not actively impose pacifism on their adherents. So, there is no historical precedent for active avoidance of military conflict in the Indian cultural sphere.

Historically speaking, from the time of Bimbisara, around the lifetime of the Buddha, in the 6th century BCE till Operation Sindoor, two months ago, there has never been a time when there was no military conflict in some part of India.

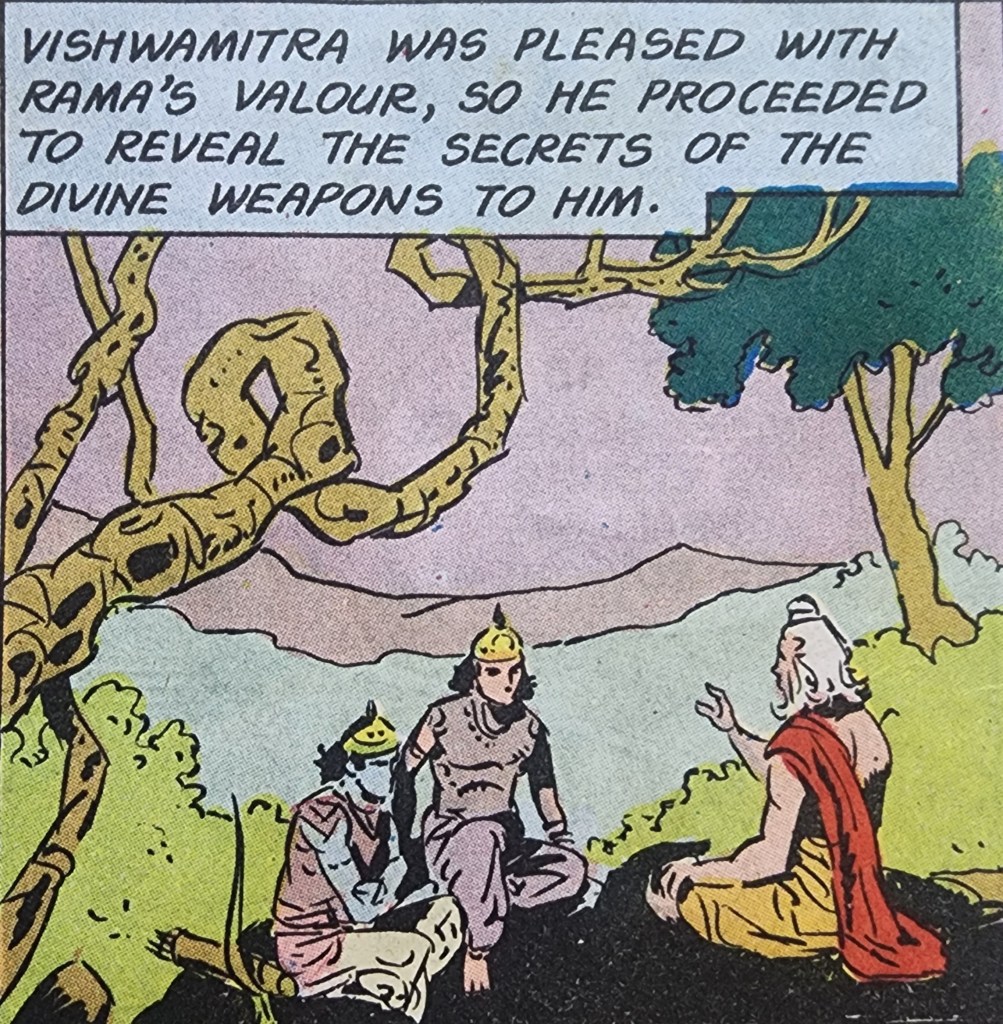

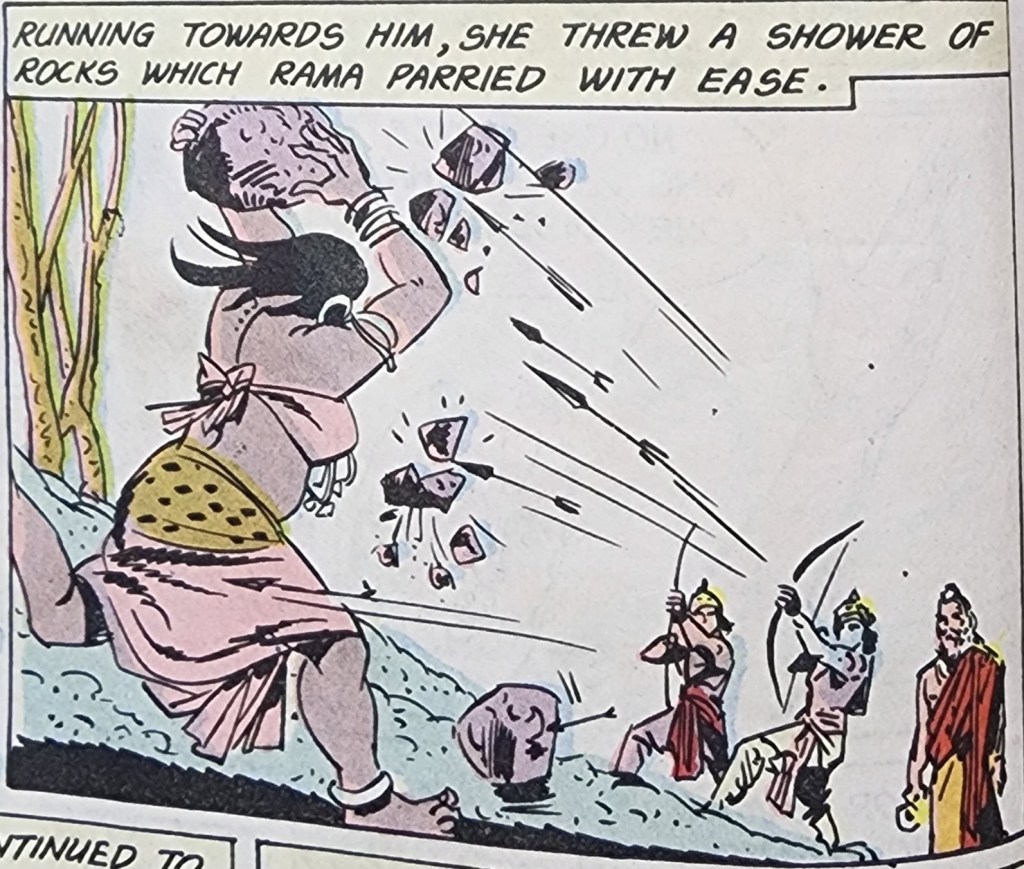

Now consider the stories from Hindu tradition. Avatāras, or incarnations of divinities are integral to several of these stories. The avatāra cycle is all about war, or violent conflict to say the least. And I am not referring to just the avatāras of Lord Vishnu. Many forms taken by the Devi Shakti also involve war. A few examples of this are seen below.

- Lord Varāha defeated Hiranyāksha

- Lord Narasimha defeated Hiranyakashipu

- Lord Vāmana defeated Bali Chakravarthy to stop the war between the Devas and Asuras

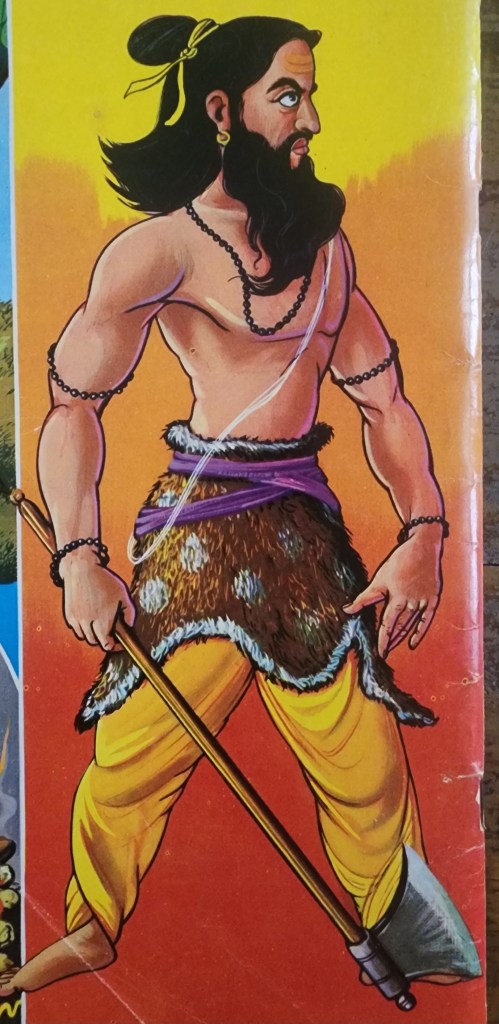

- Lord Prashurama defeated Kārtaveerya Arjuna

- Lord Rama defeated Ravana

- Devi Durga defeated Mahishāsura

- Devi Kali defeated Raktabeeja

- Devi Chāmundi defeated Chanda and Munda

In each of the example cases the defeating was at the end of a war. A war that had caused severe hardship for multitudes and brought the natural order itself to the brink of destruction. Here, “natural order” includes the way people lived (society) and the forces of nature. Also, the avatāra does not appear until all options for fighting back are exhausted.

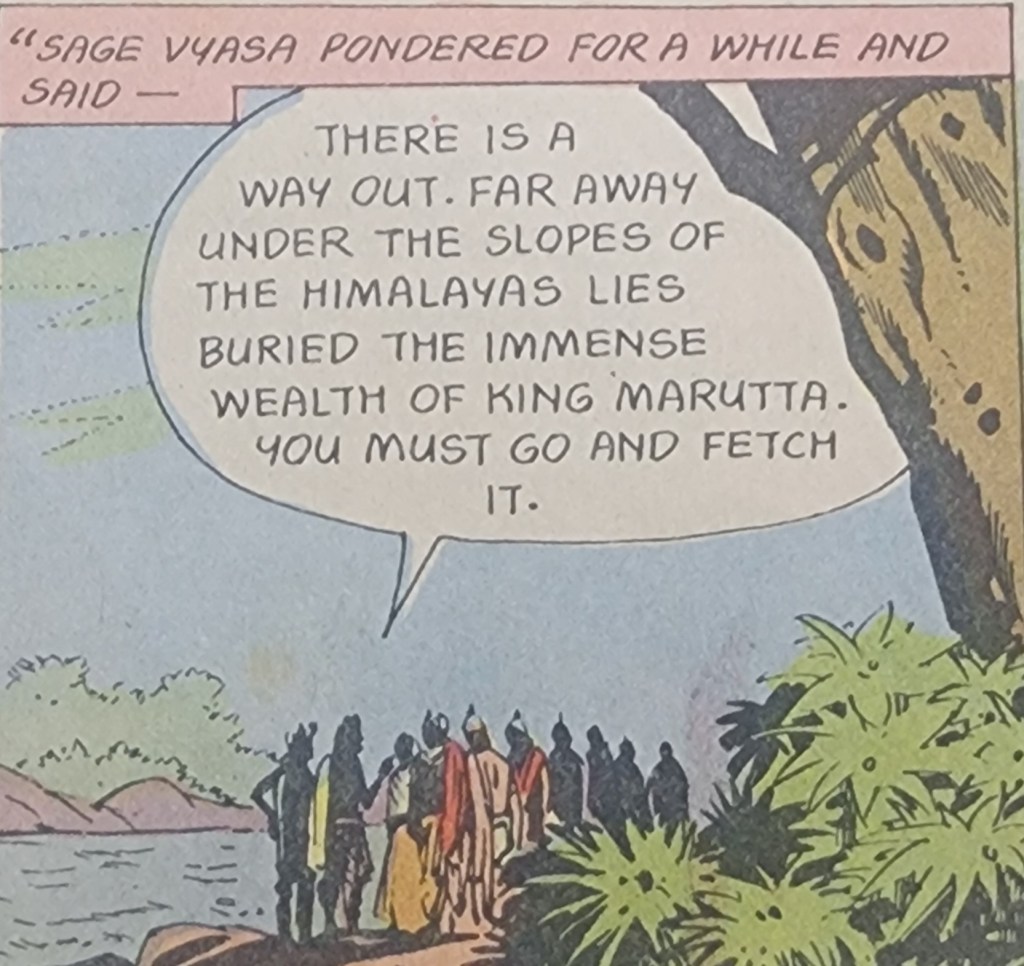

From L to R – Durga, Kali, Chamundi. Image credits – “Tales of Durga” published by Amar Chitra Katha

People, including the Rishis and the Devatās attempt to defeat the Asuras or any other adharmic or harassing entity/group by themselves. They succeed quite often. Examples of the Devas and Rishis defeating threats without an avatāra’s support are seen below

- The fight against Vrtra

- The fight against Viprachitti

- The Tārakāmaya war

Only when it is clear that they cannot survive the fight does an avatāra appear. The avatāra fighting on the side of the people, Rishis and Devatas is what turns the fight in their favour.

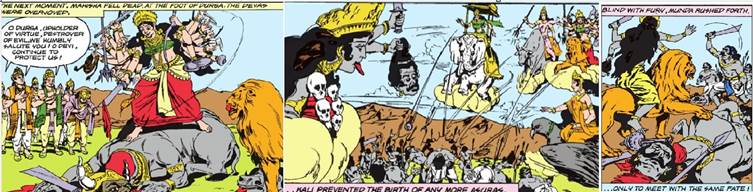

Varāha (L) & Narasimha (R). Image credits – “Dasha Avatar” published by Amar Chitra Katha

In this same vein, the Asuras are not always the ones with the upper hand. They often end up on the losing side. They have great Asura leaders who rise up, perform severe meditation/penance to achieve boons that grant them the ability to defeat all their adversaries. In all the examples above where an avatāra was needed, an Asura had acquired invincibility due to a boon, which rendered the Devas and humans powerless. If the Asura had not chosen to upend the natural order, there would have been no need for a war.

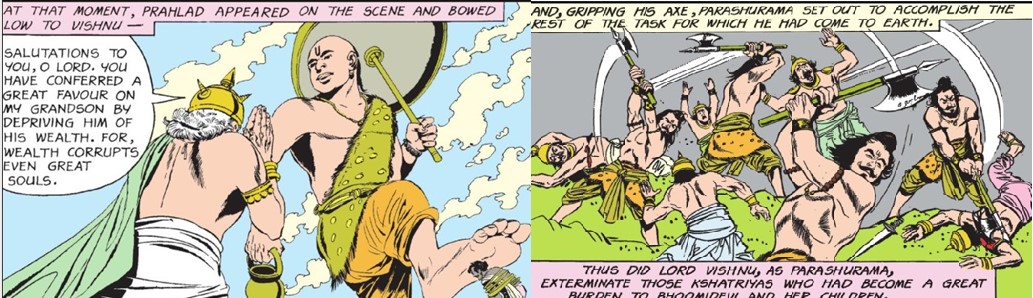

Vāmana (L), Parashurāma (R). Image credits – “Dasha Avatar” published by Amar Chitra Katha

So, it is an incessant cycle of conflict. The war that liberates the Devas and people is always celebrated. It does not mean that war is something people looked forward to. It is just that they knew that someone would want to consolidate power. This consolidation led to a reduction in the quality of life for most people. This hardship is not something that should be meekly accepted and hence a fightback is a must. This awareness that one needs to fight against unjust powers is what leads to the celebration of war, for the war destroys the injustice. Such a war can be termed a Dharma Yuddha, as against a general Yuddha (war) which is a resolution of a conflict through the use of violence. But that does not take away from the fact that even a Dharma Yuddha is a war with all the hardships accompanying one. Only when the war and hardship end is there joy, not during one.

Let’s now return to the Arthashastra by Chanakya. As a document, it had been lost for several centuries, before being rediscovered in the 20th century. But its influence over Indian political and administrative thinking has endured. I am sharing a video from the YouTube channel of the media organization “The Print”. In this video, the editor-in-chief of The Print, Shekhar Gupta, discusses a Chinese report about Indian strategic thinking.

In the report, the Chinese say that Indian actions are strongly influenced by the Arthashastra! This is some 2,300 years after the document was composed! It reinforces the influence of the Arthashastra enduring despite the original document being lost. This means that if the Arthashastra advocated constant defence preparedness, war and violent conflict were never eschewed in India at any time in her past. War was constant and preparation for it was of paramount importance as part of the duties of a king.

Watch between the 18 and 20 minute marks.

It is only in post-independence India that a collation has occurred between Gandhian Ahimsa and Pacifism. In my opinion, the Ahimsa practiced by Gandhiji was not “non-violence” and definitely not pacifism. I think Gandhiji fought a war to defeat the British belief in their civilizational superiority. This was one part of the fight for Indian independence. The other part was a violent conflict, fought by the revolutionary movement. I have written two posts in the past describing these 2 parts, where the freedom struggle is looked at through the lens of martial arts. These 2 parts together succeeded in forcing a British withdrawal, immediately after the second world war. The links to these 2 articles is seen in the notes below**.

Last, as we consider the Arthashastra, we must remember that it was NOT written by a soldier/warrior. Chanakya was a political visionary and teacher, but not a man of war. He would likely be called an “academic” if he were alive today. This shows that it is not just fighting men and women who are dangerous. Academics and people who can motivate and shape societies can be equally dangerous. These people are knowledge workers, who are dangerous because of their knowledge.

Knowledge is used in two ways. One is through the creation of technology, tactics and strategies that contribute to any war effort directly. The other is in the narrative warfare that takes places constantly and away from the fields of battle. Narrative warfare to affect the populace as a whole is a lot more important in modern times with the reach of both legacy media and social media. We all see examples of this all the time.

The use of narratives through academics and other knowledge workers, “intelligentsia” as a whole, can have a positive or a negative effect. If the communication that happens is supportive of the administration and society, the people behind it (including podcasters, influencers, journalists, reporters etc.) would be hailed as patriots. If they are conceived to be detrimental to society, these same individuals would be branded “anti-national” and that very uniquely Indian adjective, “Urban Naxals”.

The idea of both the narrative and weaponry being instrumental in a conflict, even violent ones, has always been known. This is why Turkic rulers built pyramids of severed heads and Mongols destroyed civilian populations, as a form of psychological warfare. The tales of savagery captured in documents and passed on by word of mouth induced a fear that was advantageous to the invaders.

This is also why the proverb, “The Pen is mightier than the Sword” exists. In Japanese, the pen and sword are expressed as “Bun and Bu”. “Bun” refers to knowledge and “Bu” refers to violent conflict. In modern times, we have a new term to refer to individuals who play a part in conflicts far away from any frontline. We call them “keyboard warriors”.

Notes:

* https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/13/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-1/

** https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/27/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-2/

** https://mundanebudo.com/2022/11/10/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-3/

I came across a clip on Instagram around the time that Operation Sindoor was going on. In the clip one individual was critiquing the video of another. The original video clip has a woman claiming that “we do not celebrate war”. This statement was being critiqued in the video, where an individual clearly stated that “we do celebrate war”. This person went to explain how in Hindu culture war is indeed celebrated, with examples. This video was the inspiration for this article of mine. The link to the video is seen below.