India did not have a strong martial arts culture in the last few decades, until recently. Even now, it is not prevalent in all parts of the country. In places with higher disposable incomes, interest in and practice of the martial arts is growing. In parts of the country that have a strong continuation of historical traditions, martial arts are present as well, but more as a performance art. This is not true historically though. Martial arts were a vital part of Indian culture for many centuries before diminishing in importance in the latter half of the 19th century.

Now that martial arts are making a comeback, an interesting aspect is visible. There is a cost associated with practicing the martial arts. The costs include time, effort and money. Financial costs include, tuition fees of teachers, membership fees of gyms or dojos, cost of apparel and training equipment*. Training equipment includes protective gear and training tools, which include practice weapons. Beyond this, time is spent in traveling to the place of practice and in practice itself. And then there is the effort that it takes to make time and financial resources available for martial arts practice.

The costs mentioned above were present in the past as well. For some professions, this cost was valid as it directly impacted the earning of a livelihood. This is true in modern times as well. But for individuals who are not working with law enforcement, first responders and the defence services, this cost is not necessary. The payback is not necessarily monetary. Hence, there comes a point when martial arts practice becomes discouragingly costly. This was true in the past and is true in contemporary times as well.

The cost of martial practice extends to nations too. Here the cost is justified as a nation’s sovereignty and territorial integrity are dependent on the expenditure on its martial wings, in other words, defence forces, intelligence agencies and law enforcement services. As this is vital at a national level, all nations have defence budgets.

But the defence budgets of all nations are not the same. The defence budget of the USA is almost a trillion USD! The defence budget of China is about 350 billion USD. The defence budget of India is 78 billion USD (in 2025). The cost of defence preparedness might be the defence budget but that is not the same as the cost of war.

The cost of war, depending on how long it lasted and the devastation it caused can be varying. The cost in terms of loss of life and limb of citizens is incalculable. It renders a section of the population unable to participate in any economic activity and in many cases dependent on the state, which is a necessary drain on the economy. There is also a cost associated with reconstruction and rebuilding of the economy. This is exclusive of the opportunity cost and the uncertainty of real recovery.

Unlike the cost of war, defence preparedness can have a positive effect. Over time, increasing defence budgets can lead to the creation of a military-industrial-academic complex. This complex leads to better education for large sections of a society and development of a manufacturing ecosystem. This leads to more jobs, development of advanced technologies and improved innovative abilities of a society. Defence preparedness also involves having great infrastructure in perpetuity. And then there is the boost to the economy through the export of weapons and weapon systems. All this is without even considering the benefits of the development of dual use technologies. Beyond all this there is the saying “If you want to have peace, prepare for war” (from the original Latin, “Si vis pacem, para bellum”).

It could perhaps be said that preparation for war can lead to restarting and rebuilding of a flagging or destroyed economy. A perfect example of this is the Ashwamedha Yajna in the Mahabharata, which occurs years after the end of the Kurukshetra War. The reason the epic gives for the event is that Yudishtira performs this yajna to atone for the sins committed during the Kurukshetra war. But I opine that the reason for this yajna was to kick-start the economy of the kingdoms of Hastinapura and Indraprastha.

A very large number of males had died in the Kurukshetra war. If the numbers from tradition are considered, somewhere between 3 and 4.5 million men died in the war. This meant that a large part of the working population in Northern India was dead. The coffers of all the kingdoms that participated in the war were empty due to the logistics of the war. This meant that the economy of all the participants was in the doldrums.

The Ashwamedha Yajna requires a large investment to perform and conclude successfully. To start with, a large quantity of gold is needed in the performance of various rituals and all the participating Brahmanas have to be compensated for their part in the yajna. A strong army is needed to protect the horse, the Ashwa of the yajna.

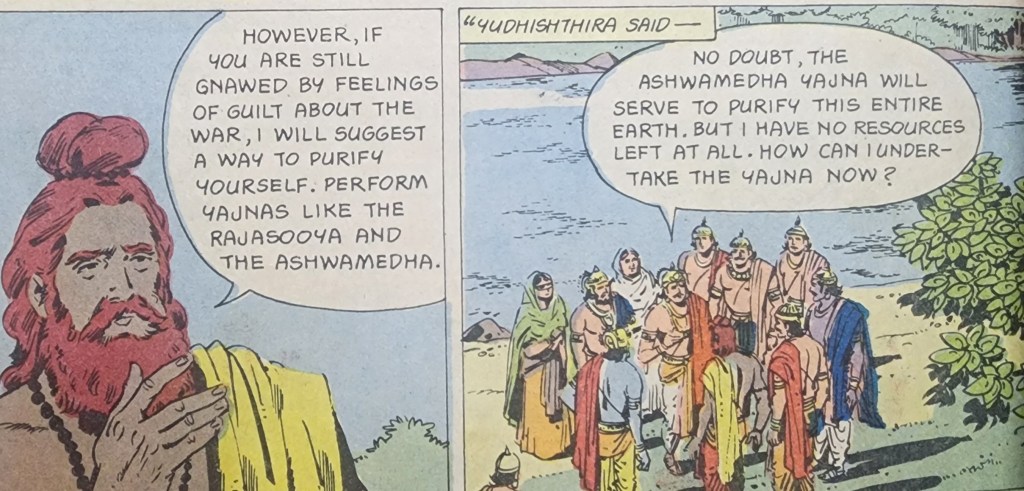

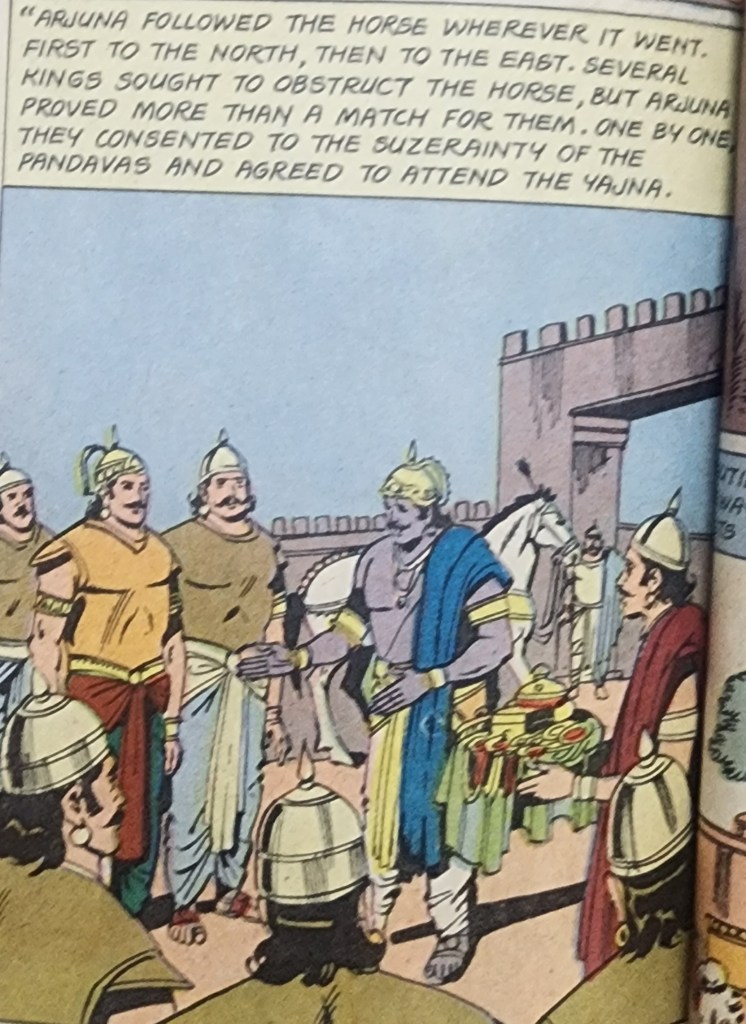

The economy does not allow for an Ashwamedha Yajna. Image credit – “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

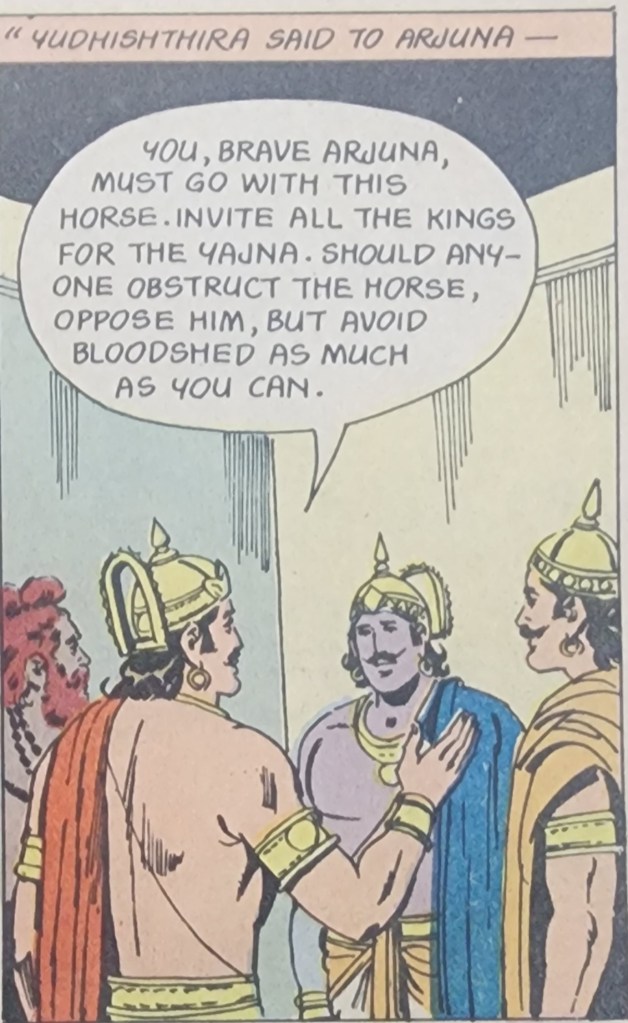

The horse would wander around for a year in various kingdoms. These kingdoms could stop the horse or let it pass through. If they let it pass through, they had to offer tribute or sign a treaty with the army of the king whose horse it was. If they stopped the horse, they kingdom that stopped the horse had to fight the army protecting it. The fact that an army was involved meant that a functioning supply chain was needed, apart from soldiers and their training.

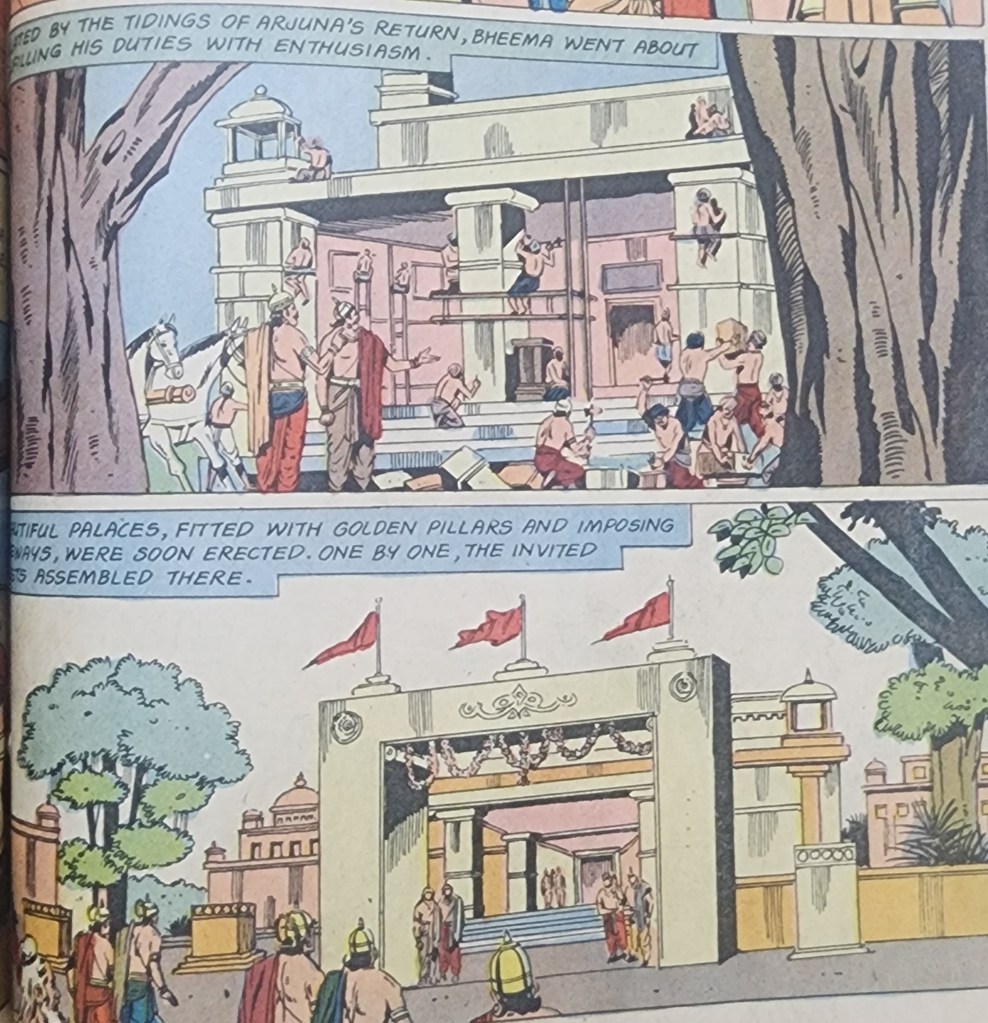

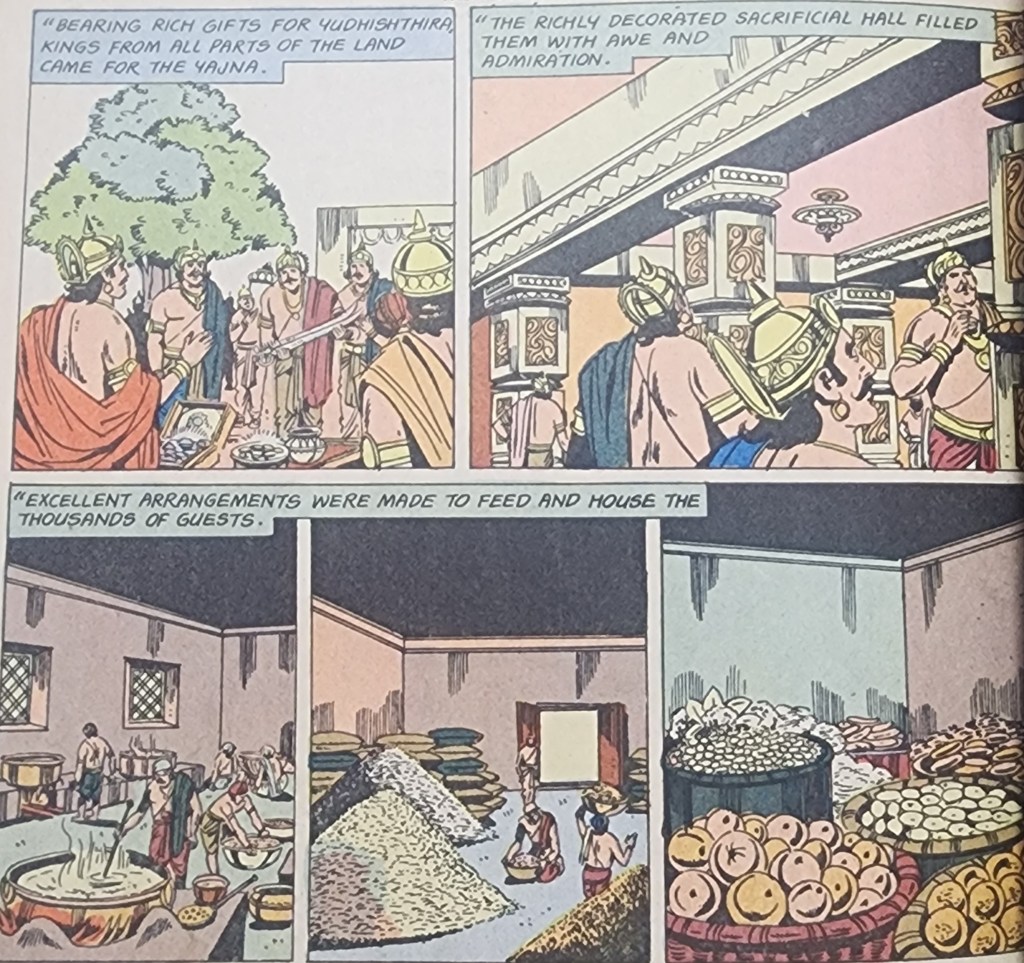

The massive logistics effort needed for the Yajna. Credit for the images- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

So, all parts of the economy have to contribute to the Ashwamedha Yajna. Food production is needed to feed the army. Industry is needed to equip the army and carry out the yajna itself. Administrative and financial bureaucracies have to be put in place to coordinate the logistics of all the activities. With all this coming up, the economy gets a jolt to restart. The tribute from the successful performance of the yajna ensures capital flows for growing the economy further.

A strong military is needed and military conflict is inevitable during the Ashwanedha Yajna. Credit for the images- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

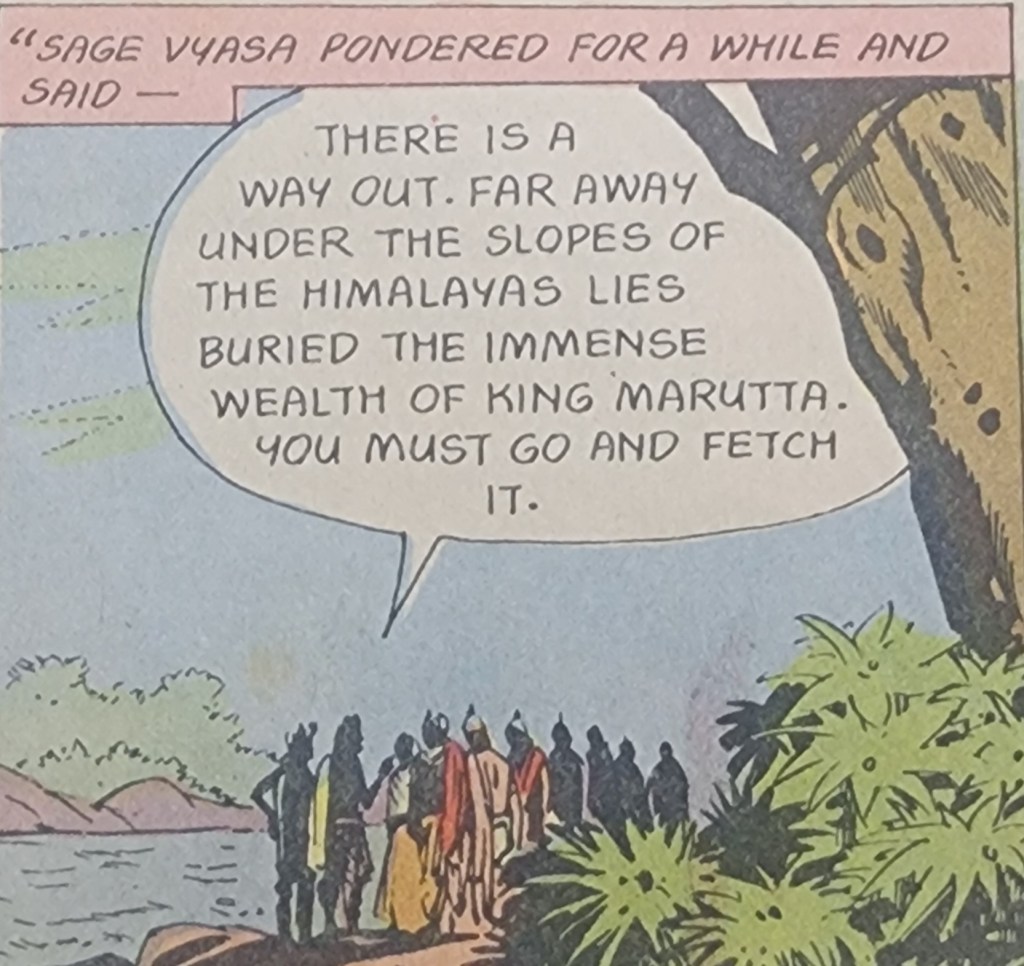

But, for a faltering/failed economy to be able to do this, an initial capital infusion is needed. This could be a loan. But in the Mahabharata, there was no institution or fellow kingdom that could afford to hand out a loan post the Kurukshetra War. So, the Pandavas dug up buried treasure. Maharishi Veda Vyasa directed them to the treasure. The treasure, a vast hoard of gold became the seed capital for the Ashwamedha Yajna and the prosperity it eventually led to.

Buried treasure is initial investment! Credit for the images- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

This wonderful segment of the Mahabharata shows how preparation for a war could lead to economic recovery. But the Kurukshetra war itself caused untold devastation. The epic is in this sense a wonderful case study for both war and its consequences and the economic recovery preparation for war can lead to (even if the defence preparedness is disguised in a sacred yajna).

Thus, it has always been about availability of resources for martial preparedness, and martial preparedness to protect and enhance economic resources and their availability. But, and it is a BIG but, this only holds where there is a democratic or a Dharmic society. A Dharmic society as I am referring to the word, is one that is defined by a clear understanding of responsibilities of the administration, even if the head of government is a king or queen who holds power due to heredity.

Wealth distribution is a must during and after the Yajna. Image credit- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

Defence preparedness is unlikely to function in the case of Palace Economies. A palace economy is one where the leader or king or dictator or the family of the same, controls all resources and distribution of the same. This control could be arbitrary, based on the will of the leadership, with no link to real world performance, hardships, challenges or threats.

A fantastic example of a palace economy is the Delhi Sultanate in India, specifically under the Mamluk dynasty and the Khaljis. All the Turkic invasions of Northern India were by palace economies. From the little history we were taught, there was no doctrine of administration that these invaders followed.

After the fall of the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughals controlled the regions of Punjab. The later Mughals, after the death of Aurangzeb, struggled to defend this region. When Ahmed Shah Abdali of the Durrani Empire centred in modern day Afghanistan invaded Punjab repeatedly, they were unable to protect the populace of this region.

Abdali was a wonderful example of a palace economy as well. He took over the regions of Afghanistan after the death of Nadir Shah of Persia, under whom he had previously served. The later Mughals were also a palace economy, but with a much smaller resource pool to go around. Abdali, on the other hand, invaded Punjab and northern India several times to acquire wealth, which was then distributed as he desired, further strengthening his palace economy. The invasions of Northern India continued until 1761 and the 3rd battle of Panipat and the invasions of Punjab continued for a few years even after that seminal event.

Abdali won the 3rd battle of Panipat, but the cost of the victory dissuaded him from ever returning to the plains of Northern India. His ravaging of Punjab is chillingly captured in the following Punjabi saying. “Khada peeta lahe da, baki Ahmed Shahe da”. It means that only what one has eaten and drunk is one’s own, the rest belongs to Abdali. It refers to the loot that ensued when Abdali attacked; people lost everything. And this kind of loot was important to keep a palace economy functioning.

The lack of this functioning in the later Mughal court required the Marathas to fight the 3rd battle of Panipat. Though they lost the battle, they successfully diminished further Afghan invasions. All further battles between Indians and the Afghans, beyond Punjab, occurred when Afghanistan was invaded by the East India Company or the British Raj. By this time, the Afghan palace economy had faltered and become dysfunctional as well. This is classic of nations where economic development did not kick off in the early modern era.

There is however a trap of exhausting one’s economy with an excessive focus on defence preparedness. I have heard a lot of people say that the USA defeated the USSR by outspending them on defence. The USSR failed economically and could not keep up with the USA. In the quest to keep itself on par with the US in defence spending, the USSR bankrupted itself.

Economic growth and development are a vital part of being able to spend on defence. The overall economy of a nation must grow continuously. When this happens, a part of the growth can benefit the defence budget. If the economy does not grow, but the defence budget keeps increasing, the country eventually ends up being a basket case. This focus on overall economic development is the reason the Ashwamedha Yajna ends up rejuvenating the national economy, because it focuses on supply chain as a whole and not just on the armed forces.

In the modern Indian context, we Indians have a threat on two fronts. Pakistan on one and China on the other. Pakistan is gradually becoming a client state of China and is being used by the latter to prevent India from becoming a competitor on the global stage for various resources. The events in Galwan in 2020 and in Pahalgam in 2025 clearly reveal that ignoring the threats will not make them go away. India will have to always be ready to militarily confront the twin threats. I include threats in the cyber and space domains when I use the term “military” here.

So, increasing defence spending is a foregone national imperative for perhaps the coming decade. This is likely what both adversaries want, to slow down India’s economic growth. China is banking on what was mentioned in my previous post, make the Indians fight themselves to keep them occupied and weakened – Pakistanis are Indians by a different name, remember**?

Will their expectation of a weaker India come to pass? Will this spending take us the way of the USSR or make our economy grow faster and become more robust? This is a question the answer to which will only become apparent in maybe 10 or 15 years. If we go about only importing technology and weapon systems, we could go either way. But if an academic, industrial military complex is developed locally, we could become a far greater economy with a stronger military and overall national power.

Notes:

* Let me elaborate with an example. We needed training katana for practice at the dojo. We could by them online, in a sports store, get a carpenter to make it or make training katanas ourselves. Back in the middle of the 2000s, an online purchase or a purchase at a sports store was out of the question. E-commerce was just beginning for only books and sports stores did not stock much martial arts equipment other than karate and taekwondo apparel and training pads. Getting a carpenter meant having a sample to go by. All of this had one serious impediment, MONEY. We did not have disposable incomes to consider this purchase lightly. We had to seriously consider if we would train the martial arts for years to come, to consider the investment feasible. Chances of continuing were always small, so the investment was unlikely as well.

That left the option of making our own training katanas. This was done with building scrap available at home, mainly small diameter PVC pipes, which were wrapped with fabric tape and held together with cellophane or insulation tape. The hardest things to make were the scabbard or saya of the sword and the tsuba or disc guard on the katana. Because these were difficult to make, the saya was given a skip and the tsuba was a piece of thermocol (polystyrene). These worked to an extent.

The drawback with the handmade equipment was twofold. The lack of a saya meant that any technique that required the drawing of a sword could never be accurately practiced. It was always an approximation. The flimsy tsuba came apart often and that led to either injured fists or to a lack of understanding of how to use the tsuba to lock the opponent’s position. So, there was pain and poor training. Both these were due to a lack of financial resources.

Our teacher back then had said that in the past, good weapons were expensive and the same was true in contemporary times as well. This was a lesson well learnt. It was as clear an elucidation of the importance of money in martial arts as any. Money leads to technology and training and both improve chances of survival.

** https://mundanebudo.com/2025/06/19/thoughts-from-op-sindoor-part-2-nothing-has-changed/