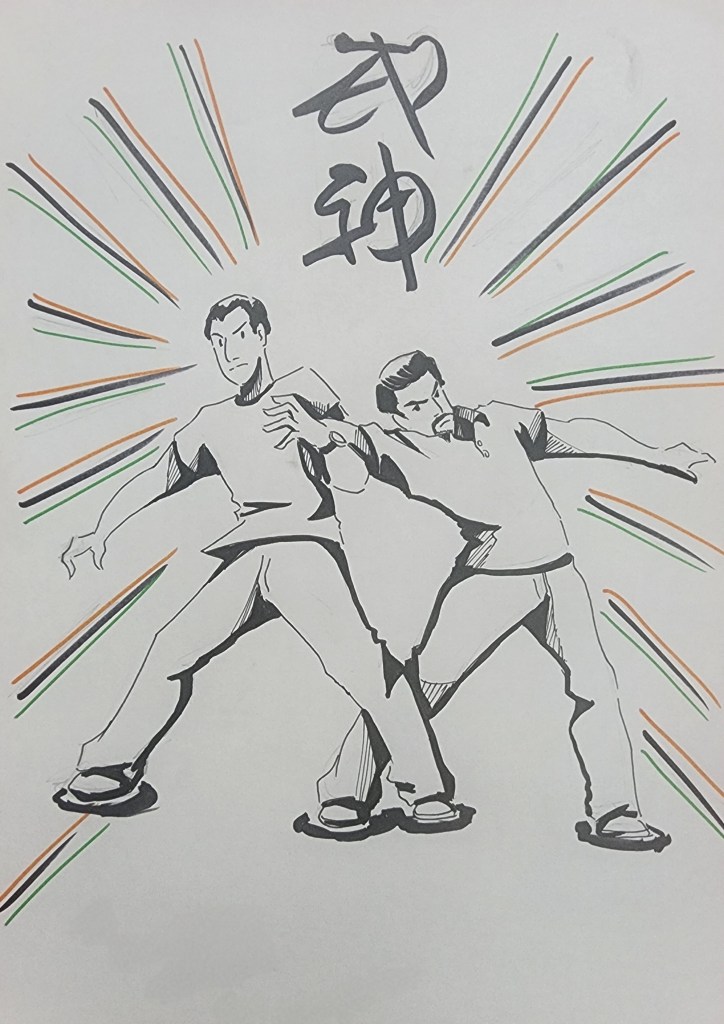

Narasimha Jayanthi was on the 11th of May this year (2025). Lord Narasimha was the 4th of the Dashāvatāra (dasha – 10, avatāra – incarnation). Lord Narasimha is a representation of incredible martial prowess. It is this prowess that I delve into in this article, to identify how his abilities are still practiced in real world martial arts, which in turn almost always have real life applications beyond the dojo.

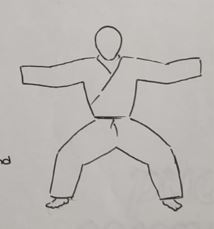

A depiction of Lord Narasimha from the 6th century CE, Badami, Karnataka, India

Lord Narasimha came to be, to specifically counter one Asura, Hiranyakashipu. Hiranyakashipu had a vara (boon) from Lord Brahma which made him impossible to kill and thus functionally immortal. Hiranyakashipu’s boon conferred the following protections on him.

- He could not be killed by a human or a beast

- He could not be killed during the day or during the night

- He could not be killed indoors or outdoors

I am now going to extrapolate a bit. I presume that Hiranyakashipu could not be killed by any weapon wielded by or controlled by a human. Otherwise, arrows would have been able to kill him in an age before gunpowder, an age when there existed “celestial weapons”, or astras of various kinds which could wreak unimaginable damage. Further, we will have to overlook the notion that humans are also beasts, just a different species. I have no idea if the boon took into consideration some specific definition for “human”.

I also presume that he was invulnerable to diseases that were cause by any biological vector, for they would constitute beasts. Considering the protection from the first point, the subsequent 2 points seem like an add-on package in case someone found a loophole in the first one. And as was the case, that is exactly what happened.

Beyond the boon itself, Hiranyakashipu was an incredible warrior, on par with the Devas. He wanted to be on par with Lord Vishnu before going out and conquering the world! This was the motivation for his gaining the boons. Further, he forced people in the lands he conquered to worship him instead of Vishnu. When I say worship, I mean in offerings at pooja, yajna and homa that are performed. There is a lot more nuance to every aspect of this story, which I cannot go into in this article*. I strongly recommend that everyone read the story in detail. Not only is it incredibly entertaining, but it is also full of conundrums and ways of overcoming the same. The connections to various happenings around the world is simply fantastic.

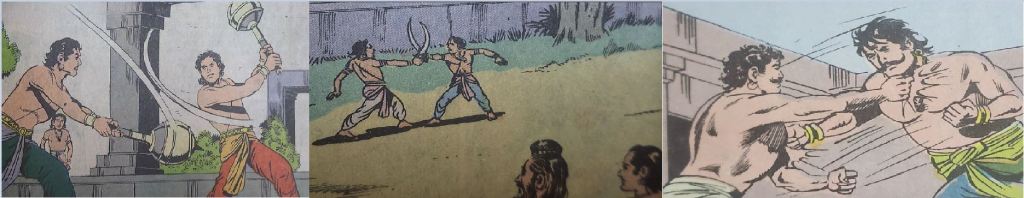

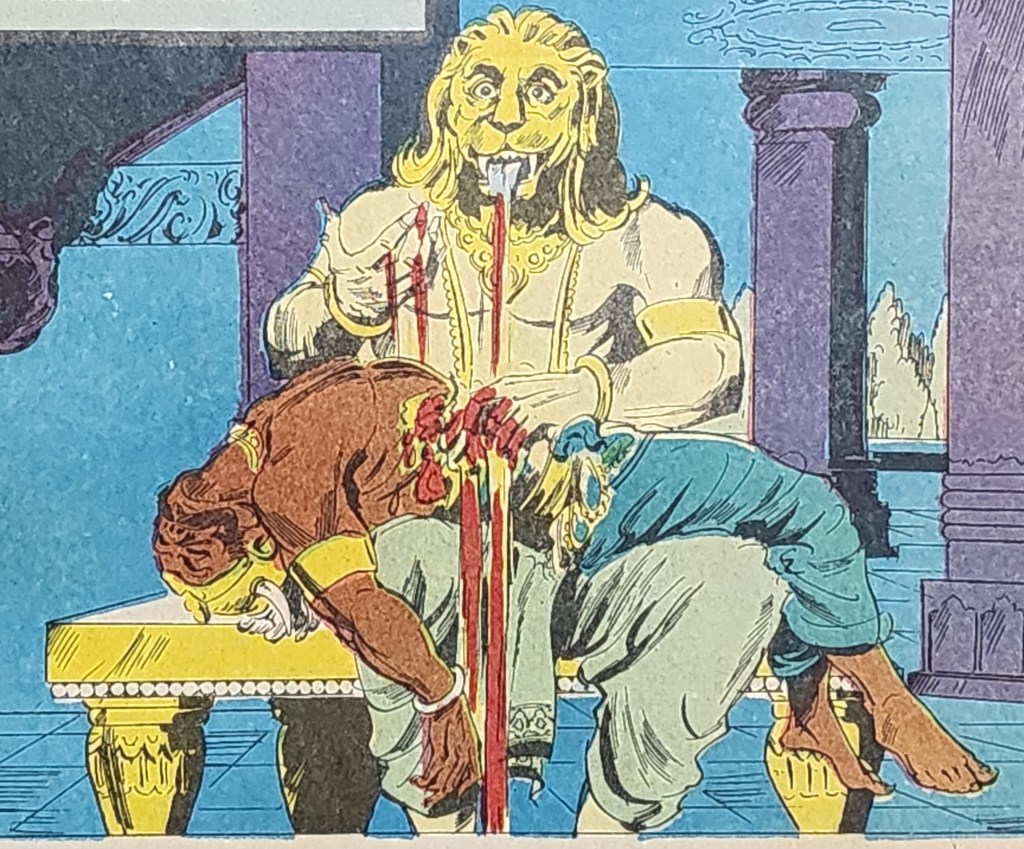

A common depiction of Lord Narasimha and his slaying of Hiranyakashipu in modern times. Image credit – “Prahlad”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

In the end, Vishnu incarnates as Lord Narasimha to destroy Hiranyakashipu. He bursts forth from a large pillar and fights Hiranyakashipu, eventually slaying him. There is a great fight between Hiranyakashipu and Narasimha, at the end of which Hiranyakashipu is disembowelled on the threshold. The end occurs by circumventing each aspect of the boon protecting Hiranyakashipu. These are as mentioned below.

- Narasimha was neither man nor animal, but both. Hence Hiranyakashipu’s boon did not protect him from Narasimha. Nara means “man” and Simha means “lion”, literally “Man-Lion”.

- Narasimha fought and killed Hiranyakashipu at twilight, which is neither day not night.

- Narasimha killed Hiranyakashipu on the threshold, which is neither inside nor outside. I do not know if the threshold was that of his throne room or that of his palace.

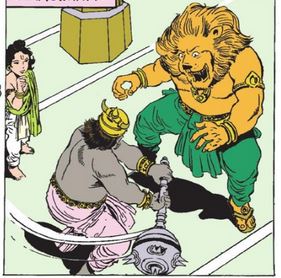

From all the iconography I have seen of Lord Narasimha, he used no weapons other than his claws while fighting the mighty Hiranyakashipu. The same were used to disembowel and kill the Asura king. This same pattern is seen even in modern days comics depicting the story of the Narasimha avatāra. At the same time, Hiranyakashipu is depicted as using a sword or mace (gada), sometimes a sword along with a shield. I must add, I guess that the claws of Lord Narasimha were exempt from being classified as a weapon as Narasimha was neither man nor beast.

Lord Narasimha fighting Hiranyakashipu who wields a mace and a sword. Image credit – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

I will now extrapolate again. Based on the way the fight between Lord Narasimha and Hiranyakashipu is depicted, I think of this as a fight between a great warrior who was wielding weapons and another warrior, who was fighting unarmed. Of course, the fact that Lord Narasimha is a God evens out the odds of going up unarmed against an armed warrior. And the fact that a God had to fight at all and needed weapons (!) shows the martial prowess of Hiranyakashipu.

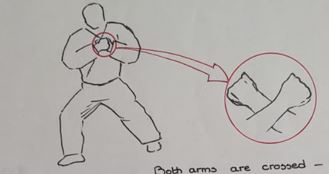

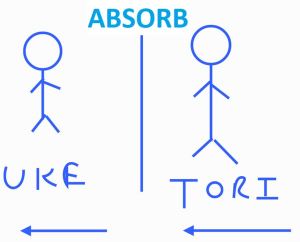

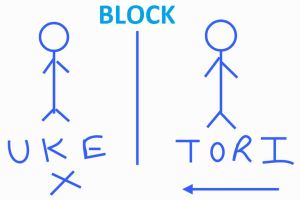

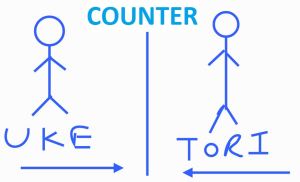

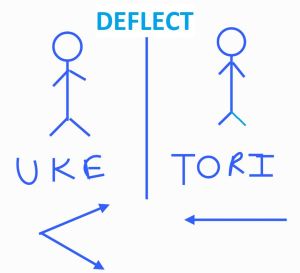

Now that the details of the fight are clear, let me look at the aspects of the same which, while fantastic, can highlight aspects of real-world martial arts and conflict management.

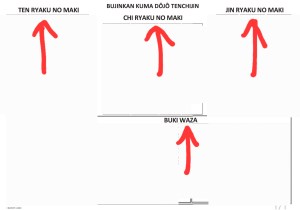

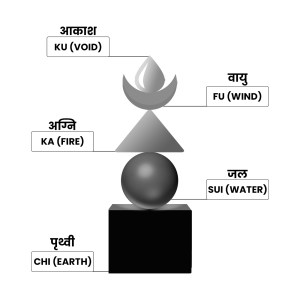

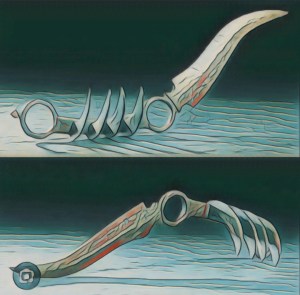

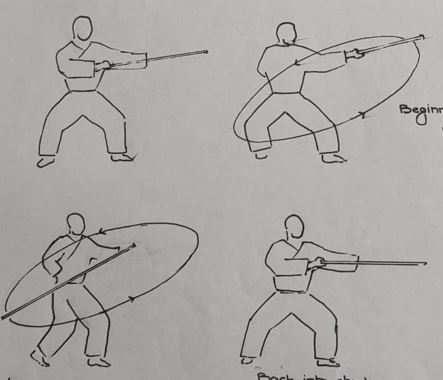

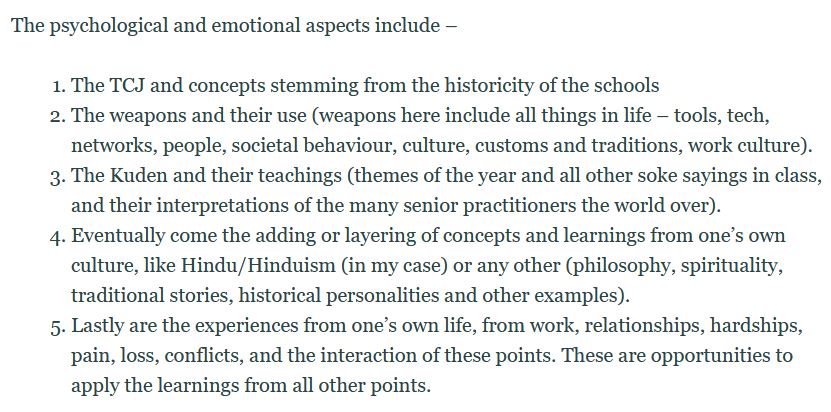

I will start with the simplest and most obvious one. The use of claws. In the Bujinkan system of martials, among the historical weapons we learn of, there are two interesting ones, which are worn on the fingertips. One is called the “Nekote” and another is the “Kanite”. Nekote means “cat claws” and Kanite means “crab claws”. Visually, to me at least, the two seem very similar.

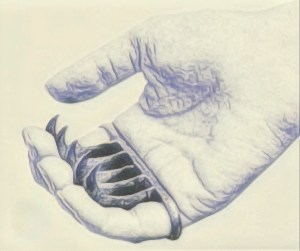

Both the Kanite and the Nekote are pointed metal tips worn on the fingertips, much like thimbles. The points on these can be used to cause damage to the opponent with a shallow stab or rakes across the body. An image is seen below of the Kanite. These are reminiscent of the claws used by Lord Narasimha to kill Hiranyakashipu.

Kanite (crab claws/finger). Image credit – “Unarmed Fighting Techniques of the Samurai”, by Sensei Hatsumi Masaaki.

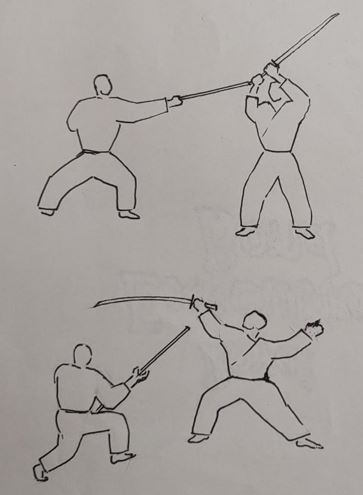

Even without the metal attachments, practitioners learn to use the tips of the fingers as weapons. There is a way of striking called “shako ken”. The fingers are used as claws to rake an opponent. Obviously, this is not meant for use against armour or any protected surfaces. It can be used to hook and pull the apparel of opponents. This strike is very similar to using the weapon called the “shuko”. The “shuko” in turn is very similar to a historical Indian weapon called the “bagh nakh”. I had written in greater detail about the bagh nakh and the shuko in a previous post, where I had discussed the martial prowess of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. A link to that article is seen below+.

Another way of striking with the fingertips is with the “Go Shitan Ken”. “Shitan Ken” is to strike with the fingers. “Go” refers to the number 5. So, “Go Shitan Ken” means “five finger strike”, in other words, to strike with the fingertips. This strike involves stabbing at the face or any other part of the opponent with the fingertips. It is not necessarily a strike or stab; it could be a push as well. To increase the force of impact of this strike, the five fingertips could be held together (like while eating). An image of each variant of Go Shitan Ken is seen below.

Two ways of using the fingers to strike (shitan ken). The fingers can be kept apart or held together for the strike.

Considering we are discussing claws here, there is a category of weapons one is taught about in the Bujinkan, called “Shizen Ken”. This refers to “natural weapons”. This in turn refers to weapons one is born with. Shizen Ken includes nails, teeth and even spit, that can be used to cause pain or discomfort to opponents with pinches, rakes, bites and just old-fashioned disgust**. 😛 The claws used by Narasimha would be called a “Shizen Ken”. But if a God that is neither man nor animal uses claws, would that then be a “natural” weapon? I am not sure. 😊

A closeup of Lord Narasimha’s claws. Image on the left is from Pattadakal, Karnataka. Image on the right is from Badami, Karnataka. The depictions are from the 6th and 7th centuries CE respectively.

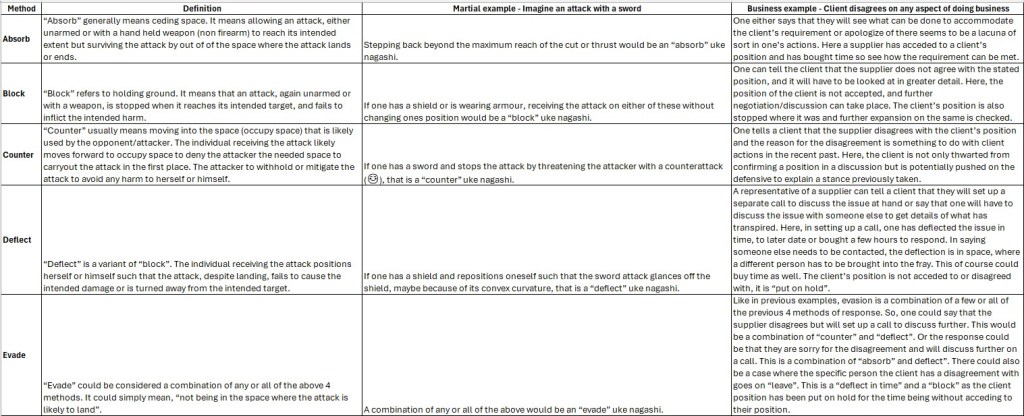

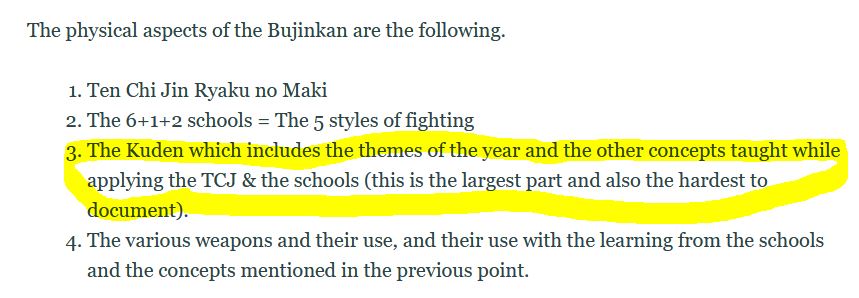

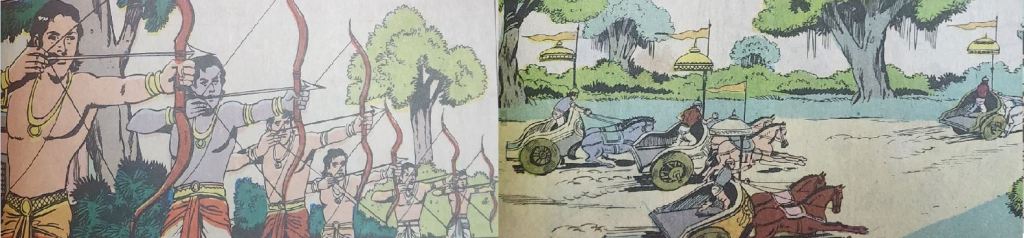

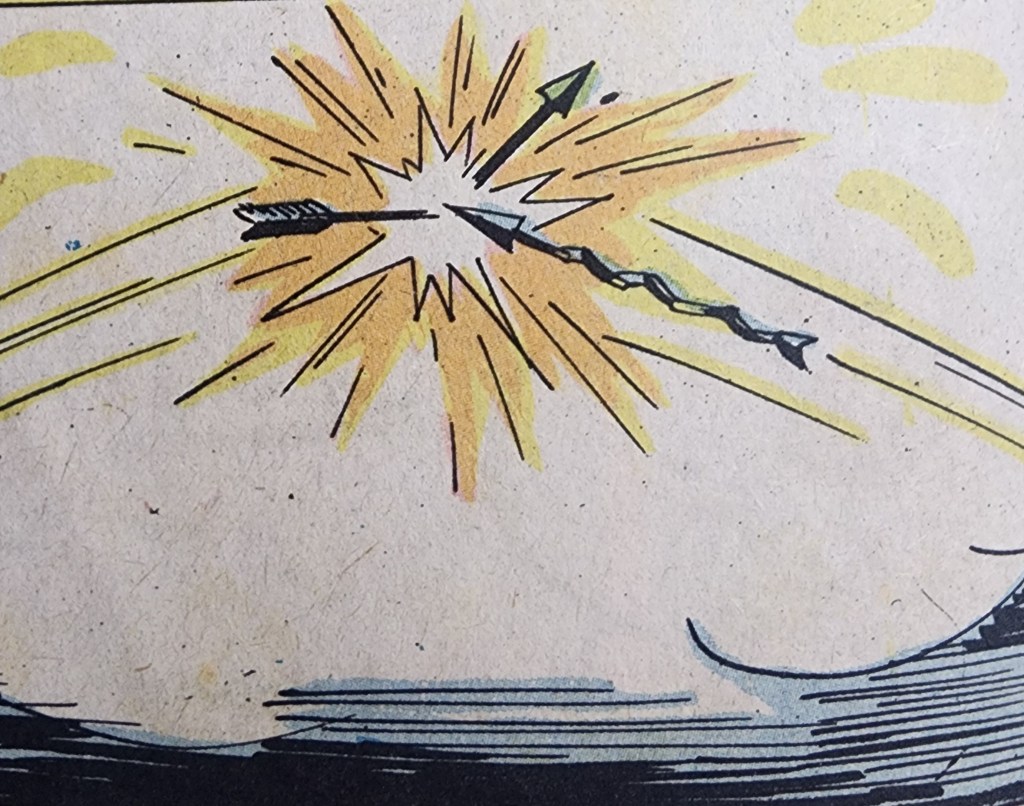

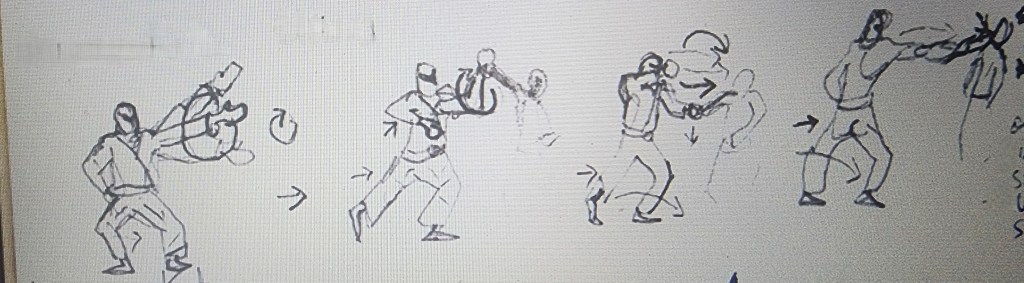

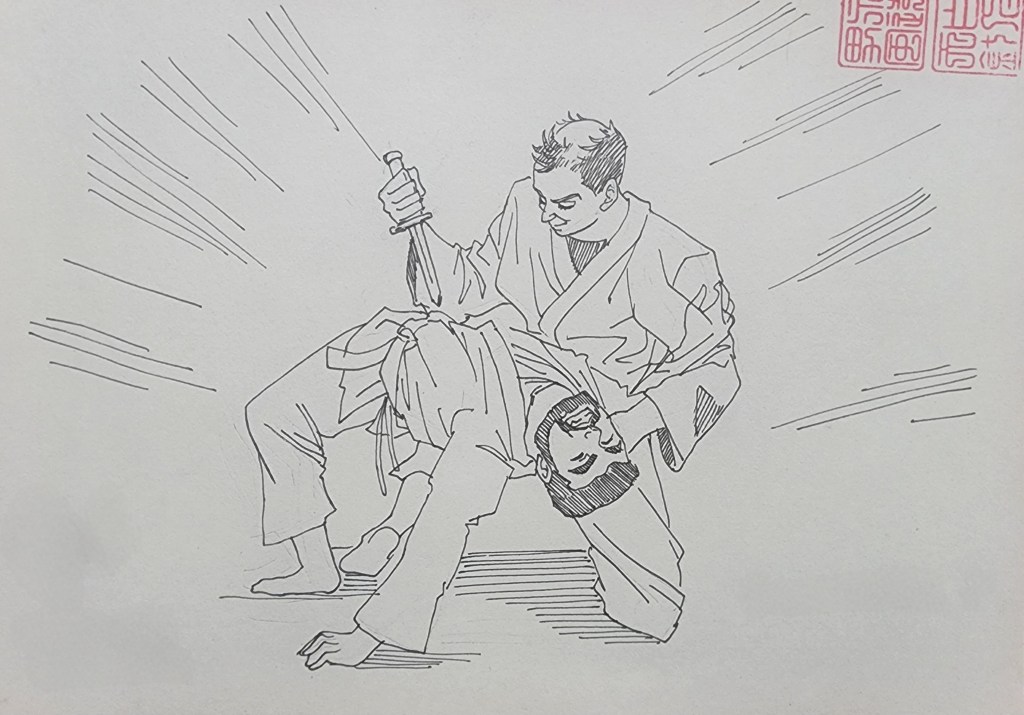

Form around 2015 to 2020, Hatsumi Sensei, the Soke (inheritor/grandmaster) of the Bujinkan, focused a lot on the concept of “Muto Dori”. We learnt from our teachers, mentors and seniors that this was a very important concept, that included not just physical aspects but also ones relating to the attitude and a spirit of calmness, self-control and of course, breathing. “Muto Dori” in its simplistic form can be translated as “capturing without a weapon”. It means that an unarmed individual can take on and perhaps defeat an opponent wielding weapons, and not just survive.

Needless to say, it is extremely difficult and needs a lot training to achieve this successfully even in the dojo, let alone a real fight. The chances of survival and success diminish considerably if there is more than one opponent with weapons. But the training of this concept is very beneficial in terms of learning one’s weaknesses, achieving a modicum of self-control and in fine tuning one’s extant abilities. Hence, the practice of this concept lasts a lifetime, if not just during one’s time as a budoka.

If we think back to the fight between Lord Narasimha and Hiranyakashipu, Narasimha was demonstrating Muto Dori all through. Hiranyakashipu was a warrior of great prowess and wielded weapons against him. Despite this, Narasimha successfully disarmed and defeated him. Narasimha would have had one goal all through the fight. Hiranyakashipu had to be either manoeuvred towards the threshold, or he had to be moved to the threshold. This means Muto Dori with an objective! Anyone who has ever gone up against an opponent with a weapon while being unarmed would realize how mind boggling an achievement this is!

I am not going into details of how muto dori is practiced because it has to be experienced. No volume of words or even videos will transmit what it entails. So, suffice it to say that as a martial artist, Lord Narasimha’s abilities, for his demonstration of Muto Dori, should be the epitome one can aspire towards.

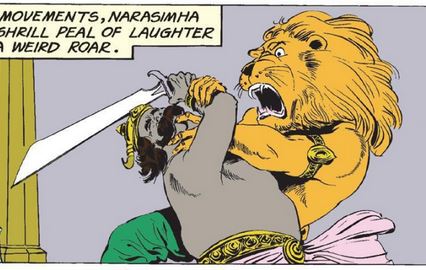

The above 2 images, the one on the right is a close up of the one on the left, are my favourites. This is a depiction of Narasimha actually fighting Hiranyakashipu in a doorway, with the threshold below them. This image actually shows a fight! Narasimha has locked both arms of Hiranyakashipu, rendering his ability use the sword and shield useless! And he is tackling the legs of the Asura king with his own! This is such a wonderful snapshot of fight in progress! This absolutely is a depiction of MUTO DORI! The image is from Pattadakal, Karnataka, from the 7th century CE.

Now I will look at some martial concepts that relate to conflict management as a whole, which also become apparent from the story of the Narasimha avatāra.

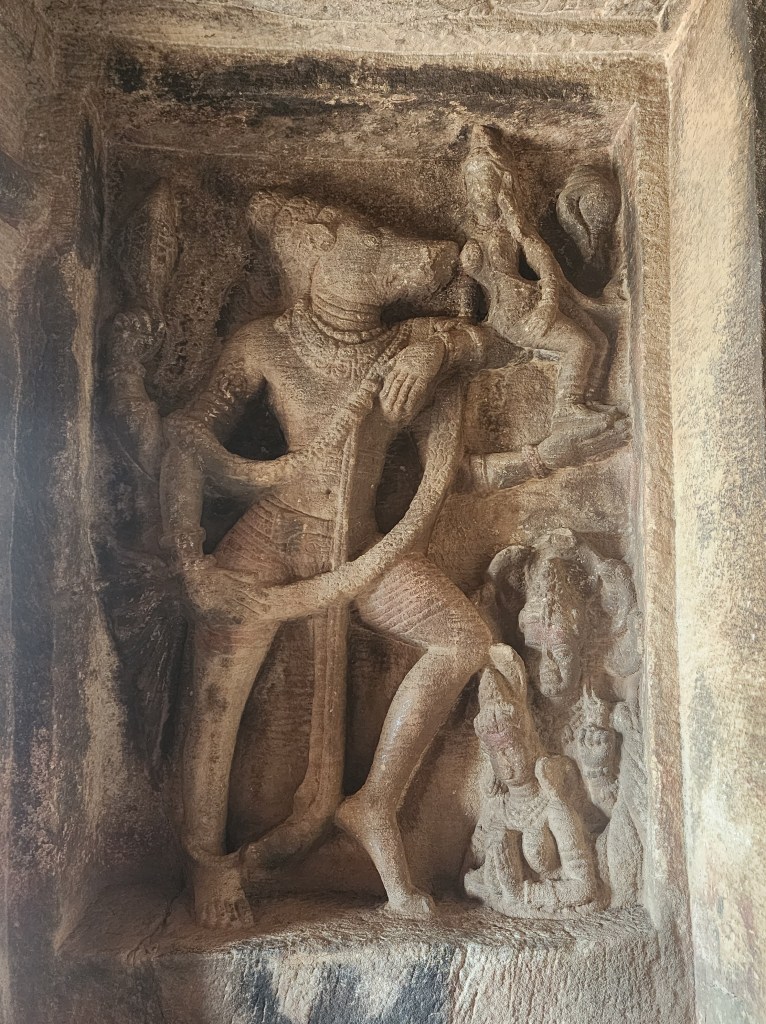

We have all been taught that to make any argument or a counter to any proposal or point raised against oneself or a team, we need to have all the necessary data. Making a point or a counter to one, without necessary and relevant information is almost foolhardy. This is something all of us are taught and practice regularly at work and in various aspects of life.

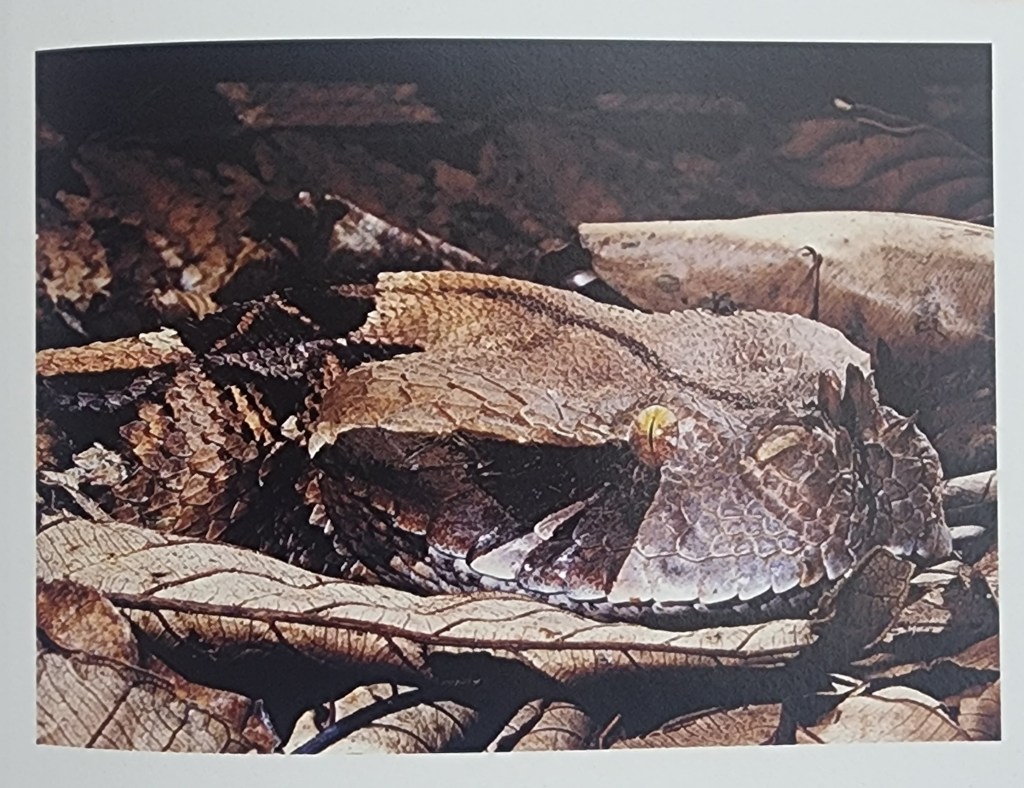

This same concept is stated in the Bujinkan, mellifluously I must add, as “Tsuki and Suki”. This is something I have heard mentioned a few times during training. Tsuki is a punch or a stab, a thrust in essence. Suki is a hole, more like an opening in armour or a gap in the same. It is a point when a thrust can be applied to cause harm to the opponent. So, one needs to “tsuki” a “suki”. One should attack an opening.

To attack an opening, one first needs to find an opening. To find an opening, one needs to know the opponent and how she or he is moving. Knowing the opponent includes the armour, weapons and objectives of the same. All of this adds up to “having all the necessary information”***. Simply put, having information is a precursor to “identifying the suki to tsuki”. The tsuki itself is the equivalent of counter a point in an argument. In a fight, an attack is a point raised, which is “countered” by a tsuki, which is a counter argument, and all of this is facilitated by information.

This flow of events in the various avatāras of Lord Vishnu is as follows. A great Asura acquires a vara (boon) from Lord Brahma. This boon ensures the invincibility of the Asura as he or she cannot be killed, though he or she is not immortal. This invincibility causes havoc in the world and the Devas, who are the guardians of the world, to lose power and go into hiding. The Devas and people of the world after failing to protect themselves despite all efforts, beseech Lord Vishnu for succour. Lord Vishnu incarnates in an avatāra to end the terror of the Asura and restore balance.

In the flow of events mentioned above, for any avatāra, I suggest that information is key! Lord Vishnu, when he appears as an avatāra, tailors the specific incarnation to circumvent all aspects of the boon the Asura possesses. In other words, the Asura creates the avatāra. Every aspect of the boon is understood, the loopholes are identified and exploited by the avatāra. This is the same as “tsuki to suki”. An opening is identified in the armour provided by the boon and a tsuki is applied to this suki. The avatāra is a tsuki and the loophole in the boon is the suki!

Hiranyakashipu realizes that the chink (suki) in his boon has been identified and is being used to attack (tsuki) him. Image credit – “Prahlad”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

All this does make one wonder, when the boon is granted, what is the confidentiality around it? Does the Asura announce to the world that he has acquired a set of powers due to the boon? Or is this gradually identified as people lose fights against the Asura? Does Brahma reveal details of the boon he has granted to the Asura, to the Devas who then report it to Lord Vishnu to device a counter? Or does Lord Brahma communicate the details to Lord Vishnu directly? Or does Brahma, who granted the boon, already know the loopholes which he reports to Lord Vishnu? If the answer to these is a “No”, does the duration of an avatāra depend on how long it takes to identify the loopholes? Or is there time taken to identify the “suki” in a boon before an avatāra incarnates? I do not have answers to any of these. Perhaps these are stupid thoughts. We are talking of Gods after all, and time does not have the same meaning in such circumstances, and I could be rambling. 😛

But these questions do lead to an appreciation of the Asuras and how they craft the boon they settle upon. I will explore this through a few examples. Many Asuras asked Brahma to grant them immortality. Lord Brahma could not grant that boon as all that was created had to end. So, the Asuras asked for boons that made them near immortal and definitely invincible, at least for long durations.

- The Asura Tāraka asked that he be invincible and killed only by a son of Lord Shiva. This was a really smart move as Lord Shiva was a yogi and in deep meditation and unlikely to ever have children. Also, he was in deep mourning after the loss of Devi Sati. Tārakāsura was eventually killed by Lord Kartikeya, the son Lord Shiva and Devi Pārvati (a reincarnation of Sati).

- The Asura Mahisha asked that he be unkillable by any male, as he was certain that no woman could best him. Devi Durga ended up killing him.

- Rāvana asked that he be unkillable by most creations of Brahma. But he did not include humans in the list of beings he would not be killed by, as he assumed that humans would never be capable of defeating him. Lord Vishnu incarnated on Earth as Lord Rama, a human, to defeat Rāvana. What is interesting is that Rāvana was defeated by the Vānara king Vāli (Bāli) and the human king Kartaveerya Arjuna, but neither of them killed him.

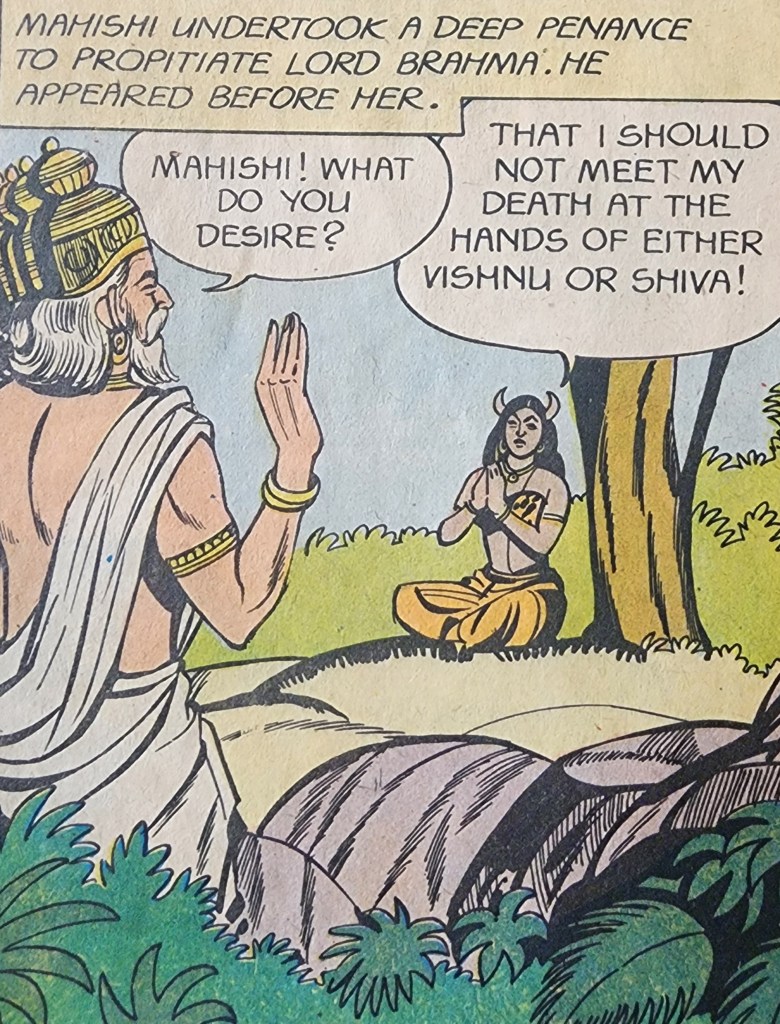

- Mahishi, the wife of Mashishāsura asked that she be vulnerable only to a son of Lords Vishnu and Shiva, both male Gods! Eventually, Lord Ayyappa killed Mahishi. Lord Ayyappa was the son of Devi Mohini (the female form of Lord Vishnu) and Lord Shiva.

There are more examples, but the ones mentioned above adequately illustrate the points I am going to make. Asuras were incredible, despite going against Dharma and attempting to upend the natural order of the universe, which would result is the suffering of vast numbers of beings. In all the examples above, the Asuras clearly had a great deal of intelligence. Their awareness of how the world existed at a given time, informed how they crafted their requests for boons.

The consequence of all these boons was that the Devas routinely lost power and the ability to perform their duties as the guardians of the 8 directions and natural phenomena (natural order). The Asuras lorded over the Earth during the time when an avatāra was yet to arrive to reestablish the natural order. Beyond the ability for great information gathering, the Asuras had great presence of mind in wording the request for a boon. The boon is no different from an inviolable contract in modern day parlance. So, their awareness of the strength of language was incontestable. All these observations together indicate that the Asuras were warriors of both physical and intellectual prowess.

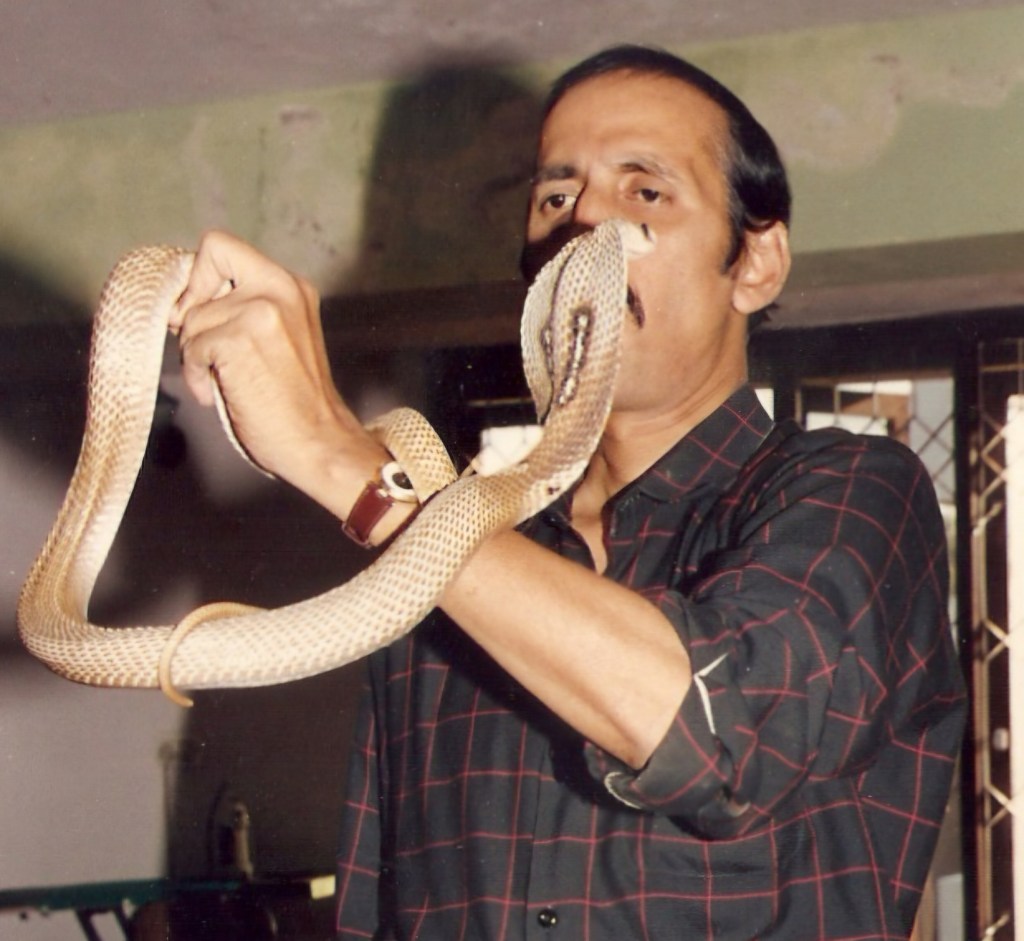

Beyond all the above points, the Asuras were rewarded for another aspect. The path to achieving a boon from Lord Brahma was a torturous one. A very long time had to be spent in meditating on Brahma, in unimaginable conditions with all earthly needs overcome. This perseverance deemed one worthy of a boon. Hence, the effort ensured that the boon was inviolable and necessitated the presence of a God on earth to overcome.

The meditation of Hiranyakashipu was brutal on his body. It resulted in him almost dying and plants and anthills growing over him. Image credit – “Prahad”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

In my opinion all of this seems like what in modern day parlance is termed “Lawfare”. It could also be called “the process is the punishment”. “Lawfare” refers to “warfare through laws”, where the actions of specific peoples are either limited or given free rein through laws of a land. “Process is punishment” is when a person is highly unlikely to be convicted of any wrongdoing under given laws, but needs to work through the due process to get oneself acquitted nevertheless. A lot of resources and time is lost in this process, which has a massive opportunity cost. This cost is the punishment, not the actual one that the law might prescribe, as a conviction is almost certainly not on the cards.

These concepts were used by the Asuras and the avatāras both, with success on both sides. The process of proving oneself as being worthy of a boon ensured that most creatures, including Asuras, Devas, humans, Vānaras and other entities, would NEVER prove themselves eligible. The process was simply too hard to complete and the punishment too much to bear!

I called the boon an inviolable contract earlier. This was despite it bending natural rules and leading to the natural order being threatened. So, it was like a law that no one could violate. The Devas, despite having consumed Amrita, were incapable of overcoming the powers bestowed by the Vara. Even Lords Vishnu and Shiva, despite being the ultimate power in the Universe, were not allowed violate the restrictions of the boon, even if they could. This is why Lord Vishnu, as preserver of the natural order, had to incarnate with specific abilities to nullify the abilities bestowed by a boon. This is undoubtedly “lawfare”, where a law is created by a boon to benefit specific individuals or groups of individuals. Eventually, the law is NOT violated and yet the beneficiary of it is destroyed by identifying the loopholes in the law!

Mashishi asking for a boon, and thus indulging in “Lawfare”. Image credit – “Ayyappa”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

If one considers the contemporary Indian context, the abrogation of Article 370, the amendment to the Waqf Act and not repealing the laws that curtail the financial freedom of temples are considered “lawfare” by people of different political leanings. There is one interesting aspect about laws in relation to this post which I have added in the notes, simply because it tangential and redundant to the idea already explained. I do recommend that people read it++.

That brings me to the end of this article. The Narasimha avatāra should, beyond the traditional significance and symbolism, open our eyes to knowledge that is not commonly known. This avatāra sheds light on the traditional martial arts and modern conflict management. And if one is not a practitioner of the martial arts, the story of the avatāra can open one to the idea that it is not a fantasy of old, the aspects holding it together are very real. Similarly, the story should hopefully reveal that conflict management is not magic and has no “silver bullet”. Intelligence, effort, time and perseverance are always required.

Notes:

* The last sukta (hymn) of the Rig Veda, as far as I know is called the Aikamatya sukta. Aikamatya roughly translates to “common opinion”. It could also mean, according to the little that I have read, “unity”. But this is not unity through homogenization. It is more like accepting all opinions and coming together. It is something like the modern Indian refrain, “Unity in Diversity”.

This sukta invites everyone to come together around the sacred fire and also states that all the Gods (essentially Gods of everyone) will be given offerings through the fire. I have heard two wonderful interpretations of this sukta. One by Mr. Sanjeev Sanyal, who is the Principal Economic Advisor to the Govt. of India and also a historian and author. Another is by Mr. Abhijit Iyer Mitra, who is a strategic affairs analyst, a Senior Fellow at the IPCS. Both are very well known in Indian media (both traditional media and social media).

Abhijit Iyer Mitra says that this sukta I am referring to is akin to the Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the 30 years war in Europe. The treaty of Westphalia allowed citizens to follow any form of Christianity that they chose. It also ensured that the state or ruler cannot mandate the religion to be followed by its citizens. It separated religion and state. It also made all forms of Christianity equal as one could not persecute the other. This is pretty much what the Aikamatya sukta states, that all Gods will be accepted and prayed to and people will come together. The sukta of course, is a few thousand years older than the treaty.

Sanjeev Sanyal expands on this idea by showing what happens if this “agreement” made through the sukta is violated. He uses the stories of King Daksha and Hiranyakashipu (referred to in this article) to explain the same. King Daksha conducted a yajna where all Gods were invited to receive offerings, except Lord Shiva. Daksha’s daughter Devi Sati was married to Lord Shiva and Daksha was against the union. In opposition to her father’s decision, Sati disrupted the yajna by immolating herself in the sacred fire. This angered Lord Shiva and King Daksha was slain.

Hiranyakashipu forced people to abandon their worship of Lord Vishnu. He further demanded that people worship him in Vishnu’s stead. This is the same as King Daksha’s actions. Both Daksha and Hiranyakashipu violated the agreement of the sukta that all Gods would be worshipped. This violation resulted in their being punished. It is like there being a consequence for violating the treaty that mandates freedom of worship and equal respect to all Gods. This is the notion that Sanjeev Sanyal has put forth. I am not aware if others have also suggested the same.

+ https://mundanebudo.com/2025/02/19/chattrapati-shivaji-maharaj-the-bagh-nakh-and-the-shuko/

** In Hindu culture there are “Navarasas”. Nava is nine and Rasas are emotions. One of these is “beebhatsa”. This is “disgust”. It is one of the nine emotions that can be evoked in an audience by any performance. The manner in which Hiranyakashipu is killed, by disembowelment, evokes a sense of disgust, or beebhatsa in the person experiencing the story. This same emotion is evoked by the manner in which Bhima kills Duhshāsana, in the Kurukshetra War in the Mahabharata.

*** In a martial arts context, “knowing the opponent” and “gathering information about the opponent” happens in the flow of the fight. It is not necessarily an activity that happens in a separate time from the fight. One needs to identify aspects of the opponent as the fight is happening. This seems esoteric, but anyone who has done any sparring knows that this happens all the time during training.

One needs to know oneself – one’s own abilities, weaknesses and objectives. And also, all these details about the opponent. In Hindu culture, knowing oneself is called “Swayambodha” and knowing the opponent or enemy is called “Shatrubodha”. I had written an article about these 2 concepts in a previous article, the link to which is seen below.

++ The guru of the Asuras, Maharishi Shukrācharya created the “Sanjeevini Vidya” by meditating on Lord Shiva. The Sanjeevini Vidya allowed him to bring back to life Asuras who were slain in battle. And they came back as they were before death, not like zombies from modern day pop culture. This was an effective counter to the Amrita that the Devas had in their possession. Amrita conferred immortality on the Devas, (for the duration of a Manvantara, if I am not wrong).

I presume that Hiranyakashipu and other Asuras who asked Brahma for the boon of immortality did so before the Sanjeevini Vidya was created. If not, there would be no need for such a boon. (And if it was later, would the boon hold if they were brought back after death? I have no idea). Anyway, the Asuras used Brahma’s boons to counter the Devas who had Amrita.

Eventually of course, the Devas gained the ability of Sanjeevini Vidya through subterfuge and a honey trap operation. Why they needed it though, I have no idea, as they already had access to Amrita. Was it to find a counter to the Vidya? Again, I have no idea. In my opinion, this conflict between the Devas and Asuras ended when Bali Chakravarthy was confirmed as the next Indra after the Vāmana avatāra. That’s another treaty by itself, something I have written about in other articles of mine, the links to which I am sharing below. All of these events can be considered technological warfare and “lawfare”.

https://mundanebudo.com/2023/11/24/dashavatara-budo-part-1-issho-khemi/

https://mundanebudo.com/2023/12/07/dashavatara-budo-part-2-katsujiken-satsujiken/