There is one concept that is oft mentioned in a Budo class over the last few years. This is perhaps since focus on the essence of Muto Dori was started by Hatsumi Sensei, some seven or eight years ago. This is “Jibun no Kesu”. From what I understand, it means “throw yourself away” or “kill yourself” or “drop yourself”.

This obviously refers to dealing with the self in a combat situation. Of course, this also holds true in any conflict management situation. The concept tells anyone involved in combat to let go of one’s self. This is generally taken to refer to one’s ego. But that definition, while absolutely true, might be a bit simplistic.

The ego part is about not letting anything except the situation in the fight affect oneself. Worry about a plan that might not be going as expected, elation at a plan that is working exactly as or better than expected, thoughts about the outcome of the fight, consequences of victory or defeat, thoughts about reputation after the fight, planning for activities as a consequence of a fight; all of these could be attributed to the ego affecting the fight. Thoughts regarding all of these and maybe more, affect how completely a fighter is in the moment in a fight. It reflects on how well, or not, one can respond to and act towards an existing opportunity or threat; it might even affect being able to identify an opportunity or threat.

The other part of “Jibun no kesu”, could be regarding the physical body itself. While there is no real distinction between the body and the ego – they are the same – they can be discussed separately for learning purposes, like two subsystems of a whole. The ego is more the mental / emotional / intellectual / spiritual component which is not tangible. The physical body is tangible and more like the sensor package of a machine while also partially behaving as the mental component when it comes to reflex actions.

All the perceptions in a fight are from the physical body which houses the five (maybe six – intuition) senses. This also includes the feedback from joints, which can perceive the resistance to a fist strike, a sword cut or a spear thrust. This helps calibrate the flow into the next movement and the next and the next. The physical body also determines the possibilities of action and the limitation of what can be done despite available opportunities. Examples of this are strength in a strike, flexibility of joints, reach available to limbs and the like.

“Jibun no kesu” says both the ego and the physical body must be dropped. This is, in my understanding, an opening into the concepts of “not fighting the opponent”, “not doing anything the opponent does not want to do” and the world famous idea of “using the opponent’s strength against him/her”. These are not concepts I will attempt to explore here as such, for “Jibun no kesu” is proving to be a handful by itself. That said, these concepts and “Jibun no kesu” might seem counter intuitive, for if there is no physical body, how is the opponent to be dealt with? Or if there is no ego, is there a need for conflict management at all?

The nature of the contradiction mentioned above is partly the answer as well. If a lack of ego can lead to a lack of conflict, wouldn’t that be great? And if there is no need to deal with an opponent, is there an opponent at all? And thus, is there no conflict either? And if that is the way to deal with a conflict, isn’t that awesome? No effort, but conflict gone! It is like opponent comes to fight a rock, but realizes there is no need to and goes away. Perhaps, one can learn to be a rock for a duration of a conflict and revert to being human? Does this work?

The answer to the above question is twofold. On the mats, while training a martial art, the answer is a yes. It is not something that can be explained or taught. But is something than can be learnt and definitely experienced. The experience is mostly personal, but quite often is sensed by the opponent and fellow trainees around the person experiencing “Jibun no kesu”.

The answer to the question off the mats, in real life, which might involve conflicts not involving a physical fight, is maybe, and many a time, no. This is because, the definition of a conflict, where a conflict begins and ends and who is an opponent are not clear. What is a threat and what is an opportunity are also hazy in outline. And if the conflict is with people one cares about or at least does not wish to actively harm, all of this is magnified manifold.

With this longwinded introduction, let me get into some examples of what I perceive as examples of “Jibun no kesu” from stories (perhaps history) of Hindu culture. This perhaps adds to the answers or leads to interesting and revelatory questions.

All of us Indians have heard of severe Tapasya being performed by several individuals in stories from our Itihaasa and Puranas (Tapasya is sometimes translated as “penance” in English, but this is simplistic in my opinion and hence I shall not use this translation and stick to the original word). The reason for the Tapasya (sometimes called Tapas) is varied, as are the Gods they perform Tapasya towards. Most popularly, individuals perform Tapasya to please either Brahma or Shiva, in order to request boons that will enhance personal abilities of said individual that helps him/her achieve great personal power and glory. Examples of this would be Hiranyakashipu, Ravana, Rakthabeeja, Bhasmasura and other Asuras who wanted personal power enhancement and also revenge.

Hiranyakashipu loses himself in meditation & plants and anthills grow over him

Image credit – “Prahlad” published by Amar Chitra Katha

There are of course several Sages who not only perform yajnas but spend time in meditation and Tapasya (the two could be the same or different, for Tapasya can also be effort towards an objective) to understand the Universe and in turn achieve abilities that can be extraordinary as a consequence. Examples here would be the many great Sages/Rishis can curse commoners (Agastya cursing Nahusha), Devas (Durvasa cursing Indra) and even the Trimurthy (Bhrgu cursing all three of the Trimurthy) to great effect due to their abilities gained as a result of Tapasya, though the purpose of their Tapasya was never to be able to curse or grant boons to great effect. Examples of boons granted by Rishis would include Durvasa granting Kunti the ability to request children from the Devas and Parashara making the stench of fish disappear from Satyavati. Another interesting case here would be Gandhari, who, due to giving up her vision and being a devotee of Shiva, could turn the body of her son Duryodhana impregnable the one time she decided to use her sight, though this was never the purpose of either her sacrifice or her devotion respectively.

Maharishi Agastya curses Nahusha

Image credit – “Nahusha” published by Amar Chitra Katha

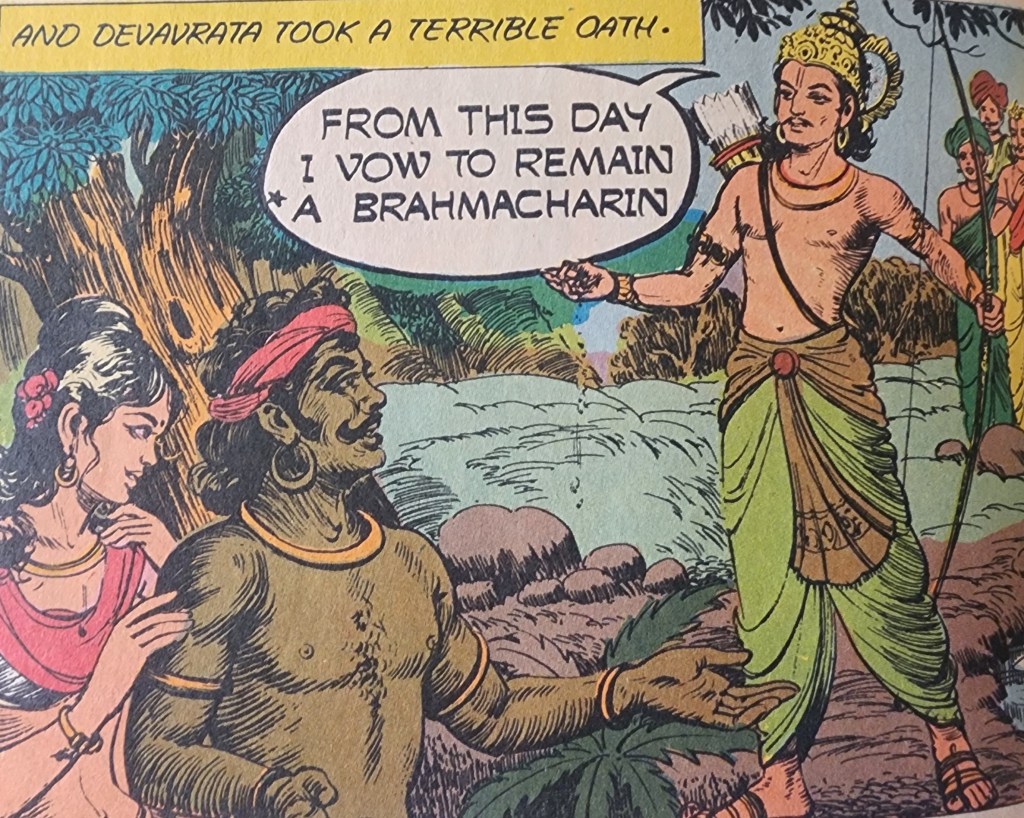

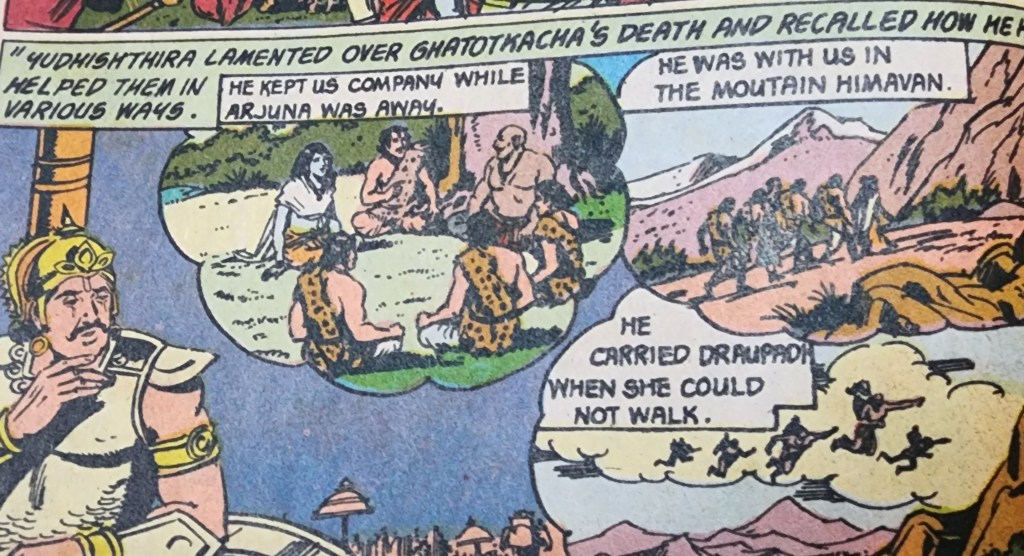

The person performing Tapasya, called a Tapasvi, can be a man or a woman and the motivation for Tapasya can also be revenge (Amba gaining the ability to reincarnate to avenge herself against Bheeshma) or simply personal help in a given situation (Satyavati remembering Veda Vyasa or Draupadi praying to Krishna during the game of dice) or consultation to address a problem (Bhima remembering Ghatotkacha to carry Darupadi while on Vanavaasa or Yudishtira remembering Veda Vyasa for help in planning the Ashwamedha Yajna).

Repentance can also be a motivation for Tapasya, like in the case of Pandu giving up the throne for a life in the forest to repent for killing an innocent Rishi or Duryodhana temporarily deciding to do the same when the Pandavas rescue him from Gandharvas. The hardship of life in a forest is the Tapasya in both these cases.

The one common thread in all of these examples of Tapasya is the ability to give up one or many things or let go of things, including “throwing oneself away” or “throwing one’s self away” (I am considering both the same). Let us consider a few examples of how Tapasya shows the extreme means in which “throwing away one’s self” is depicted in Hindu culture.

Tapasvis are usually depicted as being so completely lost in meditation that plants grow over them and anthills develop all over them. They become inanimate objects for all practical purposes. They have thrown away their physical existence, and perhaps their life itself. But they are not dead, for the object of their Tapasya is not lost and this throwing away of one’s self is what eventually brings the Gods they were meditating towards to appear to fulfil their wish. This shows how the objective of the Tapasya is not lost, even though the self might be. This is a classic case of being in the moment. The focus on Tapasya is the act of the moment and the objective is achieved by being in the middle of several moments.

The above example is throwing away of both mind and body, for all discomforts are accepted and endured, hunger is forgotten, breaths per minute are greatly reduced, heartbeats are supposedly also reduced. The body becomes an inanimate object for all practical purposes. This is an extreme example of the “transcendence of nature” gojo (shizen no choetsu). The tapasvi, while still focused on the objective and the point of focus to achieve the objective, has become inanimate. So much so that plants and ants treat her or him as a support structure, just as trees colonize abandoned buildings or anthills can grow over stones. The tapasvi is a stone with an objective, working with a strength of focus that is unimaginable.

There are also more tangible examples of throwing away one’s self, in the form of literally sacrificing body parts as offerings in a yajna (here a yajna should not be translated as a sacrifice but as a transaction, where an offering, which could be a sacrifice, is only a part).

Ravana, in one version of the Ramayana I saw on TV, performs a yajna to invoke Smashana Tara, an all-powerful form of Shakti who lords over funerary sites, to request a boon of protection against all attacks when he goes to face Rama and his army during the final battle. I am not sure which version of the Ramayana this story is from. To appease Tara and gain her audience by having her appear to him, he makes several offerings. All of these fail to appease the Goddess. So he offers his own heads as offerings in the yajna. He has offered nine of his ten heads and the Goddess still does not appear. He then chooses to offer his tenth head, even if that means ending his life, thus resulting in the failure of the yajna and his objective of winning against Rama. Tara appears to Ravana and grants him his desired boon as he is about to sacrifice his last head and thus his life. This is a case where Ravana is prepared to throw away everything, his life, meaning his body, and ego and also his objective itself, which ultimately results in his achieving the objective. That Ravana loses the fight against Rama is due to various other factors. An interesting aside is that this yajna of Ravana’s, is supposedly considered not in accordance with the Vedas. So, he was even prepared to violate his religious principles.

There is a similar tale about Rama as well in one of the versions of the Ramayana (not Valmiki Ramayana). Though this is not considered in violation of the Vedas, perhaps because it did not involving allying with aspects related to death. Rama has to offer 108 lotuses to Goddess Lakshmi to be able to successfully build a bridge to Lanka from the Indian mainland. He has gathered 108 lotuses, but when the offering is made there are only 107 for the Goddess has hidden one as a test of Rama. Rama has to take a call in the spur of the moment to prevent the offering from failing. He recalls that he is called “Kamalanayana” by Sita, which means that he has eyes like a lotus. So he decides to offer his eye as the hundred and eighth lotus. Again, this is a situation where a person with an objective is willing to throw away one’s self to achieve the same. Here again, Goddess Lakshmi stops him as he is about to pluck his own eye out and grants him his wish.

One needs to bear in mind here that in both the above examples the fact that Rama and Ravana were saved at the last minute is known only in hindsight. When they were in the act of making the sacrifice – throwing one’s self away – there was no expectation of salvation, they would have gone ahead with the throwing away of the self anyway.

Consider yet another example of a tangible letting go of one’s self. Gandhari gave up her sense of sight voluntarily for the rest of her life from the time of marriage, with no desire for anything in return. She was also a great devotee of Lord Shiva. Much later in the Mahabharata, she uses the power of her sight once, to look at Duryodhana, and the power of her unused/restrained vision combined with her devotion of Lord Shiva makes Duryodhana’s body impervious to injury. Another instance of her power is seen when she curses Krishna to have to see the destruction of his clan. This curse comes true some 32 years later. This is an instance of letting go of one’s self not for a specific objective, but gaining the ability to achieving something vitally important as a consequence of that letting go, without ever having wanted to!

Image credit – “Mahabharata 2 – Bheeshma’s Vow” published by Amar Chitra Katha

Some more examples that are as profound but mundane at the same time are the situations where parents can summon their extraordinary children from great distances with just a thought when in dire need. Satyavati, when she has lost both her sons and is facing the extinction of the royal line of Hastinapura, wishes for her other son, the great sage Veda Vyasa to appear to help consult with her and proffer solutions to her conundrum. She only has to wish his presence and he appears to help his mother. Similarly, Bhima, when he is on Vanavaasa with his brothers and their wife, only needs to wish for his son Ghatothkacha’s help and he appears to carry them with his companions. This is something that happens when the family was very tired in their travels and badly needed help. These two are instances in which the children could appear at will to help their parents due their own extraordinary abilities. But the examples are profound as the throwing one’s self away here is exemplified by what the parents gave the children in each case, both were cases where the parent had offered themselves up to another person resulting in their births. It is also exemplifying of parents letting themselves (their personal desires, time and resources) go, to raise and give kids a good life. This is mundane because parents all over the world do this all the time, since time immemorial. It is also profound because this is a “throwing away of the self” that is very well acknowledged.

Image credit – “Mahabharata 36 – The Battle at Midnight” published by Amar Chitra Katha

This idea of letting go of one’s self is not limited to just Bharatiya thinking. I quote here an interesting example I found in a book of fiction no less. This example is from the first book (I do not recall the name) of a series called “The Craw Trilogy”*. I never finished reading this book though it was interesting, and the example I am quoting is from very early in the story. The story is set in the Norse world and there is a situation which has to be answered by some spiritual women who are like leaders in the religion of the Norse before they converted to Christianity. These ladies realize that the situation facing them is dire and a new Rune needs to be created. This Rune will have the power to guide them towards a solution to the dire situation. In order to conceive the Rune, the leader of the ladies goes through a set of ordeals that I can only describe as Tapasya.

The leader of the ladies meditates while subjecting herself to extreme physical hardship for several days. I do not recall all the physical challenges, but the last one is where she submerges herself in flowing water with only her head out of water and that through a hole! And at the end of the meditation, the new rune is carved. The key point here is the meditation of the lady, which is no different from Tapasya. The lady has to let go of even the idea of staying alive to come up with a rune. While this is an example from a work of fiction, the fact that it is from a British writer shows that the idea of meditation while throwing away one’s self is not exactly a rare concept in humankind.

In the example from the novel, the tapasya lasts for several days. This allows a look at how long tapasya might have to last to achieve an objective. How long does one have to be able to let go of one’s self to achieve any objective? Or it is to be a practice that one follows all though one’s life? Or is it for the duration of any given conflict. Well, the examples from Hindu culture do not really offer any answers, except showing that the “feeling” of the passage of time is relative.

The tapasya of the Asuras looking for boons that grant supernatural abilities are depicted to take years and years, sometimes even being said to be tens or hundreds of years. But the lifespans of many of these tapasvis is also said to be extremely long. Apart from the Asuras tough, when one considers the great sages, whose life is tapasya, these large numbers are not common. But then, if plants or ants have to consider a human being an inanimate object, at least several days or weeks have to pass. So, just like time seems to flow very fast when one is solving a critical problem but when the same is considered in hindsight all of it would have happened in a short time, the duration of tapasya could be relative. The duration of tapasya would seem very long for the tapasvi, while it would be shorter for an observer on the outside or to the tapasvi himself or herself in hindsight. If one considers all tapasvis to be normal humans with the same frailties, this would make sense, for normal humans are pushed to the edge of life during tapasya and that does not take too long, even though the abilities gained post tapasya would make such a previous life for the tapasvi hard to imagine due to the sheer magnificence of the same person after the abilities granted by the tapasya.

Having discussed the prevalence of “Jibun no kesu” in Hindu civilizational memory, are there examples of what could affect the practice of the same? As everyone who has attempted to apply “Jibun no kesu” would know, the concept is fantastic and sexy, to be able to transcend one’s nature by throwing one’s self away. But difficult to the point of impossibility to apply and even harder to practice, for anything more than a few seconds, or minutes at best.

This same is shown in the stories from Hindu culture as well. Whenever one is performing tapasya, especially Asuras, their opponents, the Devas try to break the tapasya with distractions that satisfy all human senses. The tapasvi is distracted with the choices food and drink, the greatest comforts and an appeal to human lust; when Apasaras are sent to distract and break a tapasvi’s ability to throw away one’s self by bringing them back to their “senses” and the desires of the self.

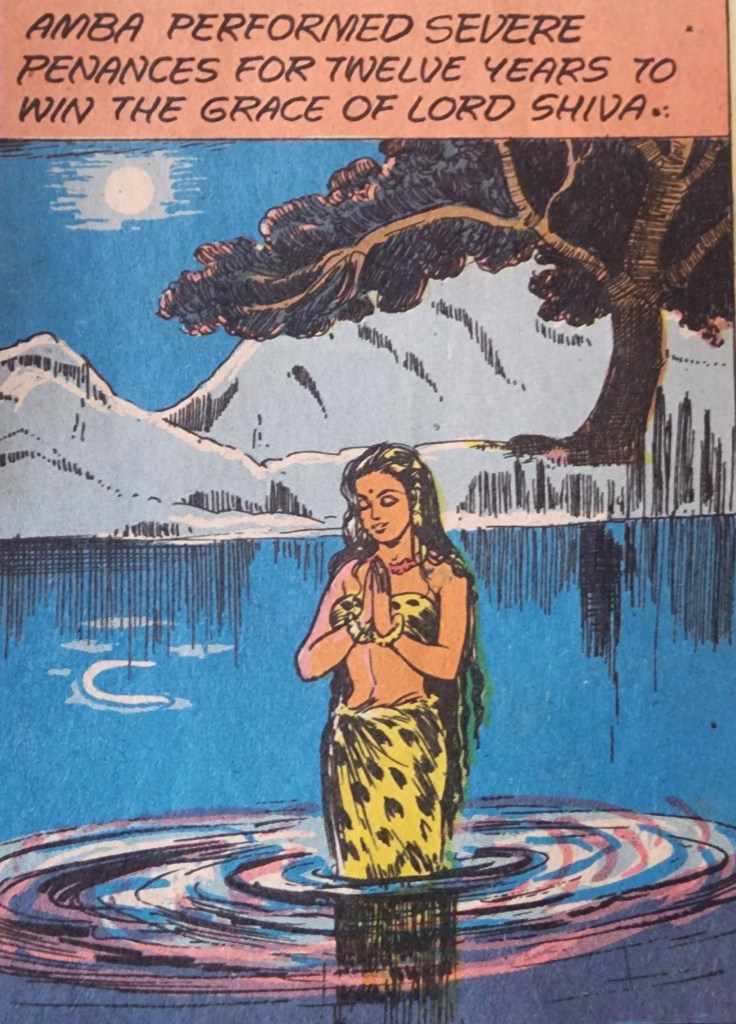

What is interesting is that these distractions seem to be used mostly against tapasvis who perform tapasya with a focus towards a single objective, like revenge or the gaining of superhuman abilities to achieve power or wealth. They are not seen to be used against sages and especially not against tapasvis who are women. Perhaps because the duration of the tapasya is a lot longer and interspersed with normal life and thus leaves one less vulnerable towards catastrophic tapasya failure. However, it must be said that women tapasvis, at least in my limited knowledge are never vulnerable to distractions and seem to have greater focus. This is seen in the cases of Parvati performing tapasya to win over Shiva to be her husband or Amba performing tapasya to be able to guarantee a reincarnation in a form that ensures revenge against Bheeshma. I cannot recall if Holika (Hiranyakashipu’s sister) or Mahishi (Mahishasura’s wife) encountered distractions from the Devas in their tapasya for the ability to fight their foes. Perhaps it has something to do with female intuition (Ku no ichi factor?) that lends itself better to transcend challenges?

Image credits (L & R) – “Bheeshma” published by Amar Chitra Katha, “Ayyappan” published by Amar Chitra Katha

One question comes up when we speak of the distractions in tapasya and hence in practicing “Jibun no kesu”, or just when we say how it is difficult to practice – to the point of impossibility. Are there any examples of failed tapasya in stories in Hindu culture? I am not aware of any that explicitly do. However, perhaps the story of Sage Vishwamitra’s trails and travails on the path to becoming a Brahmarishi is nothing but a series of examples of failed tapasya, despite its ultimate success.

Vishwamitra first performed tapasya to acquire Divyastras (celestial or divine weaponry). With these, he failed to defeat Vasishta, who was the one person he wanted to show as beneath him. So, this is not a failure of his tapasya but of the goal he set out to achieve as a result of the success of the same. Next, he gave away the abilities he gained from his renewed tapasya, to build a second Swarga (loosely translated as Heaven) for Trishanku, who wanted a Swarga while still mortal.

After this, he performed further tapasya and yet again he had to give away a lot of the abilities gained when he failed to break king Harishchandra (an ancestor of Rama) into giving up his virtues. This is a case where Harishchandra could practice “Jibun no kesu” at all times in his life and therefore overcome the efforts of a Rajarishi (eventually to become a Brahmarishi). This is fascinating story by itself, in examining letting go and throwing one’s self away that cannot be delved into as it is a really long one.

Post this, Vishwamitra again set about performing tapasya on the path to becoming a Brahmarishi. This time his tapasya was successfully disrupted by the Apsara Menaka, with whom he had daughter (Shakuntala, wife of Dushyanta and mother of Bharatha). After these several failures, Vishwamitra did become a Brahmarishi and made peace with Vasishta, whom he came to deeply respect and become a friend of. Their relationship is borne out by the fact that Vasishta is the one who recommends to Dasharatha that he should send Rama and Lakshmana with Vishwamitra when the latter requests the same (Dasharatha was not keen on the same due the youth and inexperience of his sons).

The summary of Vishwamitra’s experience suggests two things. Except with the incident with Menaka, he always was successful in his tapasya on the path to becoming a Brahmarishi. But perhaps his tapasya on the road of life towards the goal of becoming a Brahmarishi, was not. He was unable to let go of his self in that he was trying to outdo Vasistha or deliberately achieve impossible goals against the will of the Universe. His extraordinary abilities did allow him to temporarily do that, but at the cost of the original objective. It was much later and after several attempts that he did become one of the greatest Brahmarishis, when he could give up his need for outdoing Vasishta. His real “throwing away of his self” was when he could eliminate is own need to be superior to someone else, and just be a Brahmarishi with his knowledge, experience and abilities.

So, from the above observations, “Jibun no kesu” has been prevalent across times in our country. But why was this the case? How did the practice of “throwing one’s self away” influence anyone other the one doing the throwing away? Some of the effects of the extreme tapasya by tapasvis is depicted in the way nature reacts to the same. Extreme weather events like gale force winds, very heavy rain, extending to earthquakes, volcanoes and even meteor showers are described as being caused by the focused power of the tapasya. The weather events are so incredible and destructive that people and even Devas pray to the God who is the object of the tapasya to please grant the boon of the tapasvi to put an end to the inclement weather. Perhaps the Devas who are responsible for the elements lose control of the same due to the effect of the tapasya and hence would rather the tapasya end and they regain control!

Perhaps because a tapasvi becomes a part of nature like a rock or a tree or ants in a colony as he or she lets go of one’s self, the ability to be one with nature and not apart from it allows the tapasvi to affect it more? Or maybe just by introducing an unexpected element to an ecosystem, like to an inanimate object with an objective (a tapasvi who is practicing “Jibun no kesu”), the whole system is thrown out of whack? Either way, this is what is described in some stories.

In reality, this perhaps works in reverse. In a plain old physical fight or a more complex conflict of the mind, if one can practice “Jibun no kesu”, he or she ceases to exist as an opponent to the other. So, instead of affecting nature, one becomes a part of it, like the aforementioned tree or rock or ants. So, the person fighting has nothing to fight against, just as one would not consider a tree an enemy. This greatly increases the probability of the conflict ending. So, just like tapasya might affect the weather and thus force Devas to force the Gods to grant a wish, here one nullifies a fight by removing the opponent, by removing the self, of the same (if the ego of the fighter or the need to fight is eliminated, why is there a fight!). As the saying goes, it takes at least two to have a fight, there can’t be a fight with just one.

Lastly, we observed that tapasvis might have a specific objective (service to a community, revenge, wealth, power, knowledge etc.) or one’s life itself might be tapasya (which leads to great acts when the time and space call for the same without this act being the objective of the tapasya). In both cases, a tapasvi achieves great things by throwing away one’s self.

Similarly, what could be the objective of practicing “Jibun no kesu” in a real fight or conflict with others. It does seem that the effect of tapasya in the stories and “Jibun no kesu” in reality are inversely proportionate – tapasya causes nature to react, while “Jibun no kesu” allows one to become an indistinguishable part of nature – the objective of “Jibun no kesu” is simple and small in real life. It allows one to survive or perhaps be happy, as the case may be, for another moment, and then another and then another. Hopefully one can survive a conflict for another second, minute, hour, maybe many years and perhaps forever.

* Wolfsangel series by M D Lachlan (Mark Barrowcliffe)