I recently participated in a podcast on the YouTube channel, “Boom Booth Studios”. In this podcast I discuss various aspects related to martial arts and its benefits in modern day living, with the host Sameeksha P N. I am sharing the podcast for the current post. The video explains it all, I do not need to write more here.

hinduism

Thoughts from Op Sindoor, Part 5 – The enormity of all that happens in the background

Some 25 years ago, I read the book “Every Man a Tiger” by Tom Clancy and General Chuck Horner. This was a non-fiction book published in 1999. It was about the air operation during the First Gulf War, also called the Kuwait Liberation War. General Chuck Horner was the commander of the Allied air forces during that war.

I had read very few books about military history at that time and most of those were about the Second World War. The interest in modern warfare had been kindled in many of my generation in the aftermath of the Kargil War in 1999. It was also in the latter half of the 90s that satellite television had fully taken off and there were several series related to military technology and spy craft on the Discovery Channel and the National Geographic Channel.

At that time, I had only read one book, “Despatches from Kargil” by Srinjoy Choudhary, about Indian military history and that was related to the Kargil War. This book had been published in late 2000. “Every Man a Tiger” was more of a history book than the other because it had been written some 8 years after the conclusion of the First Gulf War. If I recall right, about a quarter or a third of the book deals with the transformation of the United States Airforce (USAF) after the Vietnam War.

This part of the book details how the USAF improved its quality management, adopted new technologies and improved its focus on logistics. This part of the book is dull compared to the parts describing the action and management of the war. But in hindsight, it shows a remarkable level of foresight in the leaders of the USAF in the years between the Vietnam War and the First Gulf War. And this part of the book is what inspired me to write this article.

I had not and still have not read many books about Indian military history. This includes military history post 1947. This is partially because not many military history books were popular in the social circles I grew up in. This in turn could be because this genre was not stocked in the libraries that were frequented back then. It could just be that the genre was not very popular in general.

I always thought that not much had been written about recent Indian military history*. Perhaps this is true in comparison the number of books written about Western military history in the same period. But it turns out that quite a few books were indeed written, and I was not aware of those until they were mentioned on YouTube videos discussing Indian military history. That being said, I have also heard from retired Indian military leaders and thinkers that there are not enough books about contemporary India military history, thinking and strategy. I am sharing a link to a video that specifically discusses this issue.

This video elucidates how Indian military history is not well documented.

But, irrespective of the lack of books for Indian citizens to read about the evolution and improvement of the Indian armed forces, the forces are clearly doing a great job despite all the constraints they face. The evidence of this is in the actions taken during Op Sindoor, which occurred between 7th May and 10th May of 2025. The actions reveal that the armed forces are continuously learning and adding to their repertoire of abilities, processes and technologies.

I am guessing it is extremely difficult to make a movie about the awesomeness of military planning. It is a continuous activity and incremental in nature. It might not make for great viewing in terms of the action and drama of actual fighting involving humans. This challenge is likely to increase going further. This is because war will be taken over to a significant extent by technology, from drones to stand off weapons to beyond visual range missiles to using AI in target acquisition. Pilots will likely be on the ground or far behind drone swarms and the target will never be seen by any operator, except through sensor packages.

During the years since the pandemic, we civilians have seen news about war all the time. It started with the Armenia-Azerbaijan war which introduced us all to drones taking centre stage and legacy systems like tanks and artillery guns being vulnerable. This was followed by the India-China stand-off in the Himalayas, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war (with Operation Spider’s Web being the latest news-maker from this war), the war in Gaza, the Israeli actions against Hezbollah, the clash between Pakistan and Iran, the fight against the Houthis in Yemen, Op Sindoor and most recently, the war between Israel and Iran (Op Rising Lion).

In India’s case the face off with China was more about maneuvering and not about technological superiority. The one deadly clash that occurred did not involve firearms! But the conflict prior to this, involving Pakistan, did.

Post the Pulwama terrorist attack where 40 CRPF personnel were murdered by a suicide bomber, India carried out an air strike using Mirage 2000 aircraft against a terrorist training centre on Jabbar Top in Balakot in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Pakistan retaliated the next day with Operation Swift Retort. In this operation, India lost a Mig-21 Bison aircraft while Pakistan lost an F-16. India also lost a helicopter to friendly fire. The pilot of the Mig-21 was taken prisoner and released a short while later. 200 or more terrorists are supposed to have been killed in the first Indian strike.

This short skirmish did not see the use of drones. At this time, India still did not possess the Rafale fighters which carry the long-range Meteor air to air missile. The S400 Triumf was not available for long range air defence either. Both of these were on order but had not been delivered yet. At the same time, Pakistan did not have the J10C Chinese fighter carrying the PL15E missiles. It did not have the Chinese air-defence and cruise missiles either. So, this skirmish was similar to what had been seen in the previous decades.

And then the Armenia-Azerbaijan war happened in 2020, over the Artsak or Nagorno-Karabakh region, which changed everything. This was followed by the Ukrainian defence against Russia with drones and Russia’s adaptation to this new kind of war. This started in early 2022 and is still going on. The defence forces of the whole world learned from these 2 conflicts and air defence became a facet of great importance. The defence was vital against low-cost drones and rockets and also against man-portable guided missiles that target attack aircraft and helicopters.

The Israeli layered defence system, comprising the Arrow AD system, the David’s Sling system and the Iron Dome emerged as an example to learn from. These proved their abilities in the Israeli war against Hamas & Hezbollah starting in late 2023. But the Israeli system was recognized to be very expensive for all countries to emulate. The cost of the interceptors far exceeded that of the drone swarms and cheap rockets and artillery shells they defended against.

Fast forward a year and a half to Op Sindoor and this changed. A new Indian example that could be emulated had been battle tested. I have heard it said that for the first time, the cost of the interceptors that took down drones launched by Pakistan was lower than the cost of the drones themselves. Indian Air Defence systems took down missiles fired by Pakistan and military aircraft as well. I have also heard it said that the layered air defence system India demonstrated between May 7th and 10th came as a surprise both within India and without.

This video is an example of everyone’s surprise at the effectiveness of Indian air defence.

India’s air defence system, based on my limited knowledge, consists of the AAD (Advanced Air Defence – it is an anti-ballistic missile Air Defence system), the S400 Truimf, the MRSAM, the Akash missiles and the Zu-73 and L-70 guns. There are also snipers, shoulder fired missiles and “non-kinetic” systems like lasers and jammers to take down drones.

In this video, between the 28 and 35 minute marks, the speakers discuss “Grene Robotics”, one of the organizations whose equipment was used in Indian air defence during Op Sindoor. Grene Robotics has developed a system called “Indrajaal” (Indra’s Net) for air defence.

The AAD used to intercept ballistic missiles was likely not used during Op Sindoor. The S400 was supposedly used to take down Pakistani aircraft, including one Swedish Saab Erieye 2000 AWACS at a distance of 313 km! This system also prevented the PAF from rising to take on the IAF on the 9th and 10th when Pakistani bases and command centres were destroyed. The MRSAM or Akash is supposed to have intercepted Pakistani Ballistic missiles. The intercepted missile is supposedly the Fatah-2 or the Shaheen. Chinese CM400AKG missiles were also supposedly used against the S-400 but were intercepted as well.

This video explain the events surrounding the CM400 missile.

Large numbers of drones, including those of Turkish and Chinese origin were deployed by Pakistan. Many of these were supposedly taken down by the Bofors L-70 and Soviet origin Zu-73 guns. Both of these are guns that first came on the scene in the fifties and sixties! India also operates other old air defence guns & systems like the Tunguska and Osa, the Pechora and Igla. All of these are very old weapons!

But the game changer as a whole was the Akashteer system. This is a network that connects the IACCS (Integrated Air Command and Control Centre) of the Air Force and the air defence systems of the Army and Navy. This networking ability apparently identifies an aerial threat and designates the correct system to neutralize it. So, expensive systems are not utilized for smaller threats. This system supposedly uses AI to report all threats also ignore ones that can cause no real harm (missiles that might fall in fields are simply ignored and not intercepted).

In this video, the speakers describe at a high level, the “Akashteer” system used by India for air defence.

The major threat that assets like fighter aircraft face as seen in modern warfare are surface to air missiles (SAM) and shoulder fired missiles manned by small groups of soldiers, as seen during the Russia-Ukraine war. The response to this has been “Stand Off” range weapons. These are weapons that have a greater range. These can be deployed from within safe airspaces and stay outside the range of the defensive munitions.

This lesson was clearly learnt by the IAF. None of the Indian aircraft supposedly left Indian air space during Operation Sindoor. Long range missiles like the air launched Brahmos, Rampage, Scalp and SAAW were deployed. So were kamikaze drones like the Skystriker and Harpy (both of Israeli origin, but manufactured in India). This learning prevented a repeat of a post Balakot-like situation. Even though a few fighter aircraft were lost (before SEAD and DEAD operations, one must add), no pilots were lost, and most importantly, all mission objectives were met.

The most incredible observation that comes up from all of the action during Op Sindoor is that the defence planners and strategists in India have done a fantastic job! They have clearly always known the capabilities of the enemy and the evolution of modern warfare. Every evolution and adaptation has been tracked and responded to! The end result is a mission that produced results, that for a civilian layman seem like clockwork! Of course, there must have been several adjustments over the course of the 4 days, but those are data for further learning by the defence forces.

The reason I mentioned the books about military history at the beginning of this article is because I hope there are some great ones about Op Sindoor in the near future. Not just a blow-by-blow account of how the events progressed, but books that detail how Indian defence preparedness evolved in the 5 or 10 years prior to the conflict. It would also be amazing to understand how the surgical strike in 2016 and Balakot related actions in 2019 affected planning and evolution of military actions.

It seems India has always learnt lessons after every conflict, be they a war with neighbours or an insurgency within the country. I am sharing a link to a video that details the same. This is a video by Shekhar Gupta, the Editor-in-chief of “The Print”. But there is also a feeling among us Indians that we do not document our military history and also that we learn lessons only after a crisis.

This video charts the evolution of India’s security architecture over the decades after independence.

Perhaps there is truth to both. But from the number of books I had not heard of and how much detail is coming out on the internet in recent times, both are not entirely true. We citizens I think, are just frustrated that we did not know more. The actions and successes of Op Sindoor certainly indicate that India has been learning continuously. The volume of data about Indian strategic evolution and military advancement in the last few years also indicates that the other lacuna (aircraft number, engine development, submarine numbers etc.) are being addressed.

I have been following content creators on YouTube who track advancements in Indian defence preparedness regularly. They track the technology, the planning, the strategy and the supply chain for these as well. Following them, I have realized that despite feeling the progress is agonizingly slow, forward movement is happening every day! For they simply would not have content to produce otherwise. Three channels I follow on YouTube, all of which produce content in Hindi, are,

There are others like Bharat Shakti and Strat News Global, which focus more on strategic and tactical issues, and less on technical aspects. There are many other content creators who focus on developments in the Indian defence space. Add to this the several retired defence personnel, who have started writing books and creating their own content on YouTube and we are beginning to move towards a resource rich phase for civilians interested in India’s military evolution.

To be more specific about the points in the previous paragraph, the 3 defence YouTube channels I mentioned, were instrumental in me knowing a lot of the systems used by India during Operation Sindoor. These channels might not know and sometimes do not reveal if they know, what is not explicit in the public domain. So, the actual status of the induction or deployment of a weapon system or network would not always be available on these channels, nor would exact technical details and numbers deployed. But the general capability and the progress of development of various systems will be known if one follows these and other such channels regularly.

For example, these channels have always spoken about the progress of the AAD ballistic missile defence. They have also spoken of the MRSAM and the multiple variants of the Akash missile system. I only knew that the MRSAM (Medium Range Surface to Air Missile) was based on the Israeli Barak-2 missile, and was jointly developed by DRDO with Israeli industry because of these channels.

I also knew that that the Indian Nagastra was used in Op. Sindoor and that the Israeli Harpy/Harop and Skystriker drones were produced locally due to these channels. Further, I know the difference between the “Sudarshan Chakra” and “Sudarshan CIWS”! 😊The former is the name for the S-400 Triumf in India and the latter is the “Close in Weapon System” (air defence gun system) being developed by L&T. I also knew the difference between the Akash missile and the Akashteer networking solution. 😊

Further, as we realize more about the development and planning of weapons based on evolving threat perceptions, what is clear is that these days war is almost as much a matching between adversaries, of R&D, Supply Chains, engineering abilities, defence budgets, communication and the actual people on the frontlines, who operate various weapon systems. It almost seems like a never-ending exercise in management, finance and technology even though they are not visible. Only the final operators of the tools of war are visible and the outcome of the deployment of weapons are known.

Of course, none of this is new. All of this has been going on for centuries, all over the world. One can only imagine the efforts needed in managing the men and animals in an Akshauhini mentioned in the Mahabharata. How did one feed and clear the dung of over 21000 elephants! How did one breed, train and manage hundreds of thousands of horses used in the Kurukshetra war!

In the historical era, Alexander’s campaigns are considered a success of his supply chain. In Roman history, we hear of the “Marian reforms”. These refer to the reforms carried out by Gaius Marius around 100 BCE, in the army of the Roman Republic. They are supposed to include changes to the composition of the army and its training. There were also supposedly changes to equipment design and how these were procured. All of this is supposed to have resulted in a more effective Roman army**. This process of evolution is heard of from every culture in all parts of the world.

The outcomes of Op Sindoor have brought to the fore the efforts that go into the procurement, maintenance and equipping of fighter aircraft and drones, beyond just the actual combat in the air. These days, aircraft supposedly never see their opponents, they are only aware of their presence and actions due to electronic sensor packages. These sensor systems can deploy defensive weapons when needed!

This means there needs to be an R&D and manufacturing ecosystem in a country if it has to even survive going up in the air. If the ecosystem is absent or nascent, money has to be found to procure the abilities from other nations, which means a focus on geopolitics! All this means the focus is on integration and that mystical word, “synergy”.

The achievement of objectives is more about the integration of all systems to work together than just having numbers or courage. Numbers and courage matter a lot, but do not guarantee success. I had read a sentence in a “Modesty Blaise” story, “The Warlords of Phoenix”. It goes something like, “guns make a weak man strong, but make a strong a man a giant”. In a contemporary context, this could be “numbers and courage make a weak nation strong, but integration makes the strong nation untouchable”.

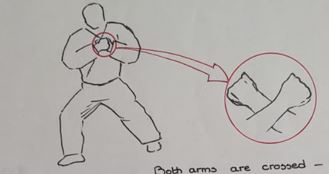

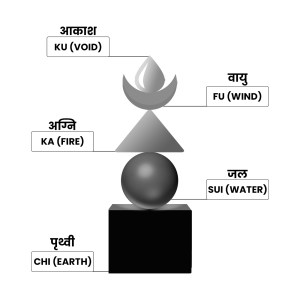

Let me use an analogy from the martial arts to elucidate further. Consider training with a spear. The spear is a stick with a pointed metal tip at one end. The stick is called the shaft or haft of the spear. Remove the shaft and the spear is a dagger at worst or a short sword at best. The advantage of range that made the spear vital in the past is nullified. The shaft is also how a wielder interacts with the weapon.

So, the shaft is what makes a spear, not the spear head! But the tip or spear head is what everyone looks at, respects, appreciates and most importantly, fears. Remove the shaft and the fear diminishes greatly.

This is exactly like modern warfare. The drones, fighter aircraft and the missiles are the tip of the spear. But the planning, management, technology, study, and finances are the shaft of the spear. Without these, the tip diminishes greatly in its ability.

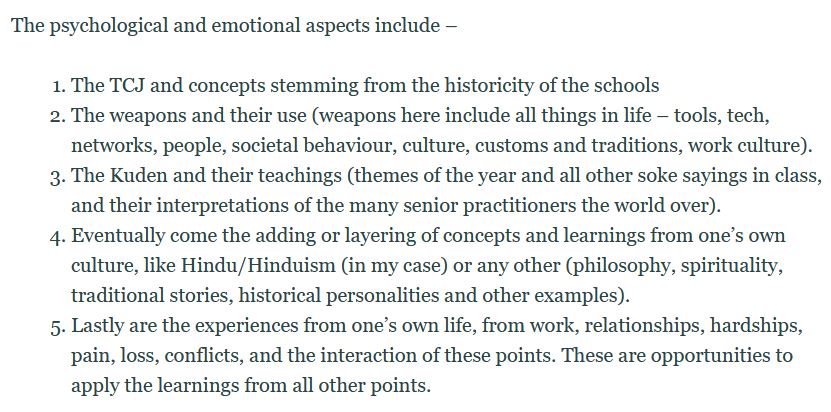

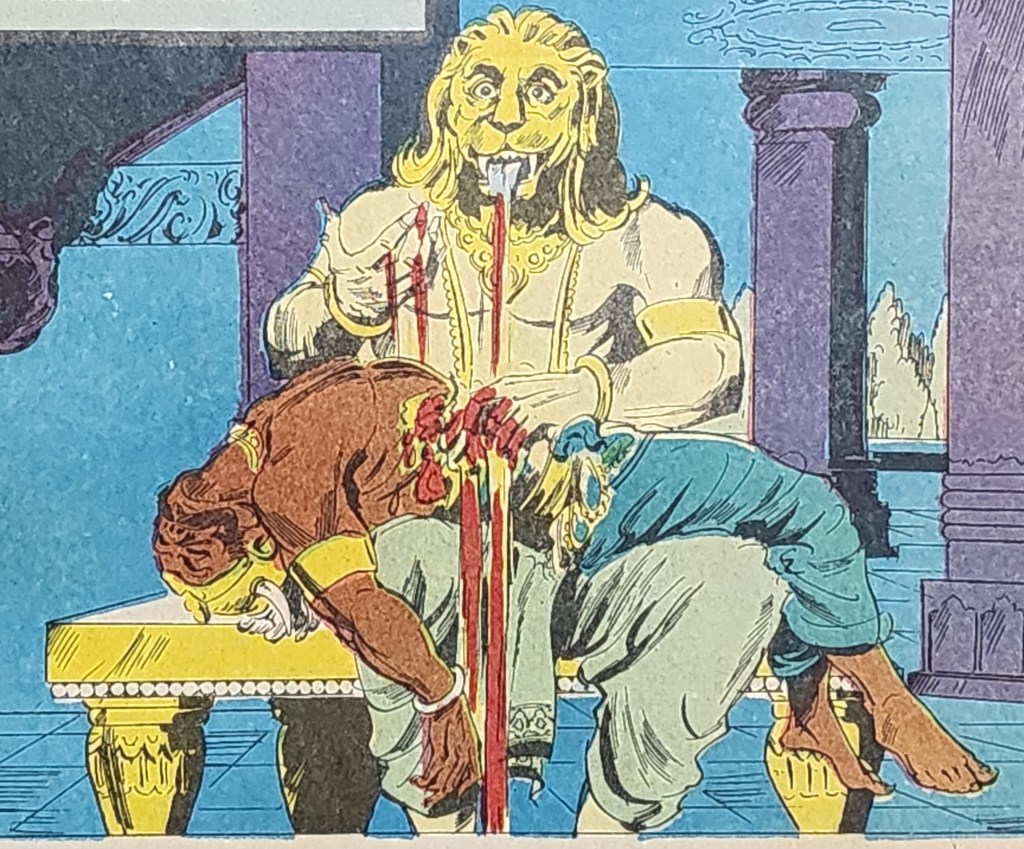

Taking this analogy further, the air defence system is like the shield or armour to the missiles and aircraft that are the spear. Historically, the shield and armour have been as important as the spear or the sword. These were used by all cultures and were always a part of a soldier’s kit for most of history. A soldier with a spear and a shield is more devastating as against one with just a spear. And a soldier with just a shield and no spear is even less so.

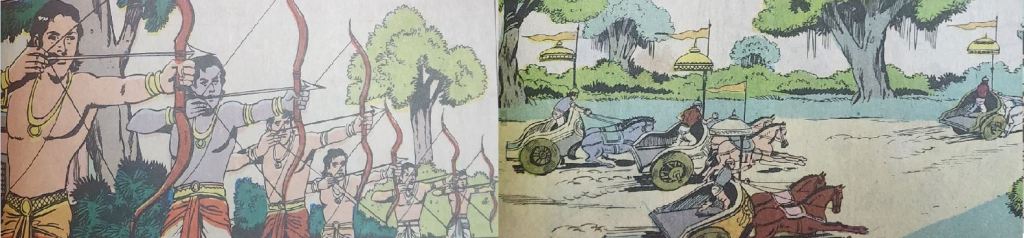

The Shield and Armour are vitally important to a soldier. Image credit – “Mahabharata 33 – Drona’s Vow”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

So, the defence system and the offensive weapon package together make for a combination that affords a greater probability of mission success. This is the integration that we discussed earlier. A lack of integration, while still capable, is not as effective as the other.

So, one of the things that Op Sindoor has done spectacularly, is to bring the focus onto the parts of conflict management that are not glamourous and are less well known. The management, planning and continuous learning that enable the successful execution of a military operation have been highlighted like never before. And we as a nation can breathe easy as the planners seem to have been doing a great job behind the scenes.

As a last analogy, martial arts training is all about drudgery. One trains for long hours for years on end, despite knowing that the need to apply the learning might never occur. This is also the most preferred situation; one never wants to fight, for the variables in any conflict are numerous. The learning from training in the martial arts are likely applied in walks of like beyond physical combat.

Similarly, the machinery that defends our nation has clearly been going full steam! One can only imagine and marvel at the innumerable hours spent over years, putting together and training with the various aspects that resulted in the success of Op Sindoor! We owe a debt of gratitude to all the individuals who played their parts in this mammoth exercise.

Lastly, just as the martial arts are likely to lead to benefits beyond physical combat, our nation’s defence preparedness will lead to greater economic development due to increased spending on R&D and manufacturing and the many export opportunities that are likely to materialize.

Notes:

* Some other books I have read and heard of about Indian military history are mentioned below. These are beyond the ones mentioned in the article proper.

- 1962: The War that Wasn’t by Shiv Kunal Verma

- 1965: A Western Sunrise by Shiv Kunal Verma

- The Garud Strikes by Mukul Deva

- The Battle of Haji Pir by Kulpreet Yadav

- The Battle of Rezang La by Kulpreet Yadav

- Nimbu Saab: The Barefoot Naga Kargil Hero by Neha Dwivedi and Diksha Dwivedi

- India’s Most Fearless : True Stories of: True Stories of Modern Military Heroes by Shiv Aroor and Rahul Singh

- There are several other books that have out in recent times!

- There is a lot more content on YouTube in the form of podcasts that details recent Indian military history and evolution

** I have heard a statement about Roman military training that goes something like, “the training is like bloodless fighting, while fighting is like bloody training”. I had heard this statement in an old series called “War & Civilization” on Discovery Channel in the late 90s. The series was based on the work of John Keegan.

Similarly, it seems that India’s success in Op Sindoor was as much about the study, planning, research, management and training when there was no fighting, as about the actual fighting during the operation.

Thoughts from Op Sindoor, Part 4 – Celebrate War!?

Wendy Doniger has said that the “Arthashāstra”, written by Kautilya (Chanakya) is a “wicked” book. She means this with a negative connotation, as the book recommends violence. She refers to the Arthashāstra’s recommendation to wage war with neighbours and maintain friendly relations with states that are not immediate neighbours.

I agree with Wendy Doniger. The Arthashāstra is a “wicked” book. But I mean it with a positive connation. The book is “Wicked Good”! And for the same reason that Doniger gives. It does not shy away from military conflict. It advocates readiness to participate in violent conflict, if the situation so demands.

Watch between the 48 and 52 minute marks. Between the 40 and 48 minute marks Ms. Doniger expresses her opinion on how Hinduism is a violent religion.

India is a secular nation. But it has a strong Hindu civilizational character that pervades a very large part of its population. Hindu culture is NOT inherently NON-VIOLENT. The worldwide popularity of Mahatma Gandhi* and his pervasive impact on our national consciousness might make some think that Hindu culture is “non-violent”. But it definitely is not, and it most certainly is not a believer in pacifism!

Hindu culture emphasizes “ahimsa”, but that is not the same as non-violence. I have written previously about “ahimsa” from a martial perspective. I will not repeat that here but will leave links to the earlier articles*. Simply put, ahimsa is about not having malice towards anyone or any nation. But that only means that one should not go looking for a fight. If someone brings a fight to you, the threat must be nullified, there can be no doubts there.

Jainism is closer to non-violence, since it tries to avoid harming any creature. But there were kings who practiced Jainism who did participate in wars. So, even Jainism is not entirely free from practitioners who had to commit violence. The other socio-religious systems in India, including Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and tribal belief systems (these are Hindu adjacent), did not actively impose pacifism on their adherents. So, there is no historical precedent for active avoidance of military conflict in the Indian cultural sphere.

Historically speaking, from the time of Bimbisara, around the lifetime of the Buddha, in the 6th century BCE till Operation Sindoor, two months ago, there has never been a time when there was no military conflict in some part of India.

Now consider the stories from Hindu tradition. Avatāras, or incarnations of divinities are integral to several of these stories. The avatāra cycle is all about war, or violent conflict to say the least. And I am not referring to just the avatāras of Lord Vishnu. Many forms taken by the Devi Shakti also involve war. A few examples of this are seen below.

- Lord Varāha defeated Hiranyāksha

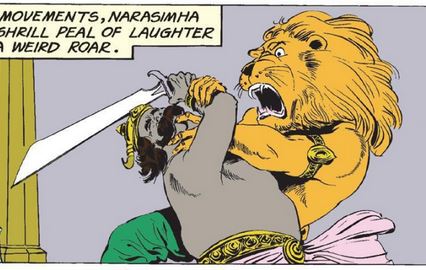

- Lord Narasimha defeated Hiranyakashipu

- Lord Vāmana defeated Bali Chakravarthy to stop the war between the Devas and Asuras

- Lord Prashurama defeated Kārtaveerya Arjuna

- Lord Rama defeated Ravana

- Devi Durga defeated Mahishāsura

- Devi Kali defeated Raktabeeja

- Devi Chāmundi defeated Chanda and Munda

In each of the example cases the defeating was at the end of a war. A war that had caused severe hardship for multitudes and brought the natural order itself to the brink of destruction. Here, “natural order” includes the way people lived (society) and the forces of nature. Also, the avatāra does not appear until all options for fighting back are exhausted.

From L to R – Durga, Kali, Chamundi. Image credits – “Tales of Durga” published by Amar Chitra Katha

People, including the Rishis and the Devatās attempt to defeat the Asuras or any other adharmic or harassing entity/group by themselves. They succeed quite often. Examples of the Devas and Rishis defeating threats without an avatāra’s support are seen below

- The fight against Vrtra

- The fight against Viprachitti

- The Tārakāmaya war

Only when it is clear that they cannot survive the fight does an avatāra appear. The avatāra fighting on the side of the people, Rishis and Devatas is what turns the fight in their favour.

Varāha (L) & Narasimha (R). Image credits – “Dasha Avatar” published by Amar Chitra Katha

In this same vein, the Asuras are not always the ones with the upper hand. They often end up on the losing side. They have great Asura leaders who rise up, perform severe meditation/penance to achieve boons that grant them the ability to defeat all their adversaries. In all the examples above where an avatāra was needed, an Asura had acquired invincibility due to a boon, which rendered the Devas and humans powerless. If the Asura had not chosen to upend the natural order, there would have been no need for a war.

Vāmana (L), Parashurāma (R). Image credits – “Dasha Avatar” published by Amar Chitra Katha

So, it is an incessant cycle of conflict. The war that liberates the Devas and people is always celebrated. It does not mean that war is something people looked forward to. It is just that they knew that someone would want to consolidate power. This consolidation led to a reduction in the quality of life for most people. This hardship is not something that should be meekly accepted and hence a fightback is a must. This awareness that one needs to fight against unjust powers is what leads to the celebration of war, for the war destroys the injustice. Such a war can be termed a Dharma Yuddha, as against a general Yuddha (war) which is a resolution of a conflict through the use of violence. But that does not take away from the fact that even a Dharma Yuddha is a war with all the hardships accompanying one. Only when the war and hardship end is there joy, not during one.

Let’s now return to the Arthashastra by Chanakya. As a document, it had been lost for several centuries, before being rediscovered in the 20th century. But its influence over Indian political and administrative thinking has endured. I am sharing a video from the YouTube channel of the media organization “The Print”. In this video, the editor-in-chief of The Print, Shekhar Gupta, discusses a Chinese report about Indian strategic thinking.

In the report, the Chinese say that Indian actions are strongly influenced by the Arthashastra! This is some 2,300 years after the document was composed! It reinforces the influence of the Arthashastra enduring despite the original document being lost. This means that if the Arthashastra advocated constant defence preparedness, war and violent conflict were never eschewed in India at any time in her past. War was constant and preparation for it was of paramount importance as part of the duties of a king.

Watch between the 18 and 20 minute marks.

It is only in post-independence India that a collation has occurred between Gandhian Ahimsa and Pacifism. In my opinion, the Ahimsa practiced by Gandhiji was not “non-violence” and definitely not pacifism. I think Gandhiji fought a war to defeat the British belief in their civilizational superiority. This was one part of the fight for Indian independence. The other part was a violent conflict, fought by the revolutionary movement. I have written two posts in the past describing these 2 parts, where the freedom struggle is looked at through the lens of martial arts. These 2 parts together succeeded in forcing a British withdrawal, immediately after the second world war. The links to these 2 articles is seen in the notes below**.

Last, as we consider the Arthashastra, we must remember that it was NOT written by a soldier/warrior. Chanakya was a political visionary and teacher, but not a man of war. He would likely be called an “academic” if he were alive today. This shows that it is not just fighting men and women who are dangerous. Academics and people who can motivate and shape societies can be equally dangerous. These people are knowledge workers, who are dangerous because of their knowledge.

Knowledge is used in two ways. One is through the creation of technology, tactics and strategies that contribute to any war effort directly. The other is in the narrative warfare that takes places constantly and away from the fields of battle. Narrative warfare to affect the populace as a whole is a lot more important in modern times with the reach of both legacy media and social media. We all see examples of this all the time.

The use of narratives through academics and other knowledge workers, “intelligentsia” as a whole, can have a positive or a negative effect. If the communication that happens is supportive of the administration and society, the people behind it (including podcasters, influencers, journalists, reporters etc.) would be hailed as patriots. If they are conceived to be detrimental to society, these same individuals would be branded “anti-national” and that very uniquely Indian adjective, “Urban Naxals”.

The idea of both the narrative and weaponry being instrumental in a conflict, even violent ones, has always been known. This is why Turkic rulers built pyramids of severed heads and Mongols destroyed civilian populations, as a form of psychological warfare. The tales of savagery captured in documents and passed on by word of mouth induced a fear that was advantageous to the invaders.

This is also why the proverb, “The Pen is mightier than the Sword” exists. In Japanese, the pen and sword are expressed as “Bun and Bu”. “Bun” refers to knowledge and “Bu” refers to violent conflict. In modern times, we have a new term to refer to individuals who play a part in conflicts far away from any frontline. We call them “keyboard warriors”.

Notes:

* https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/13/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-1/

** https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/27/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-2/

** https://mundanebudo.com/2022/11/10/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-3/

I came across a clip on Instagram around the time that Operation Sindoor was going on. In the clip one individual was critiquing the video of another. The original video clip has a woman claiming that “we do not celebrate war”. This statement was being critiqued in the video, where an individual clearly stated that “we do celebrate war”. This person went to explain how in Hindu culture war is indeed celebrated, with examples. This video was the inspiration for this article of mine. The link to the video is seen below.

Guru Poornima – The many “Sensei” in Hindu culture

Today is Guru Poornima. And I guess some of you will have received a post on WhatsApp that says there are 6 or more words for “teacher” in Sanskrit*. Some of these words are “Achārya”, “Shikshaka”, “Adhyāpaka” and of course, “Guru”. But in common parlance, the word “Guru” is perhaps the most commonly used word to denote a teacher in many parts of India.

Karate featured on the cover of Tinkle No. 220. This cover was published in March 1991.

A zoomed in part of the cover from the earlier image. Tinkle comics is published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Another word that many of us in India have heard and also denotes a teacher is the Japanese word “Sensei”**. Anyone who had watched the original “The Karate Kid” (1984) surely knew the word. So did anyone who either trained karate as a kid or had a friend who trained the same. There was even an issue of the popular comic “Tinkle”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, which discussed Karate and how it used physics to perform great physical feats (this was a tale featuring the “Anu Club”).

Like most people, I too knew that the word “Sensei” can definitely be used to denote a teacher. This is not wrong. But very early during my years as a student of the Bujinkan system of martial arts, I learned that the word had a slightly different meaning, which did lead to its meaning a “teacher”.

The term “Sensei” as used in Tinkle comics. Image credit – Tinkle No. 220, published by Amar Chitra Katha (India Book House – IBH).

The word “Sensei” as I understand it, literally means “someone who was there earlier”. This is why elders and people with great expertise arising out of experience are also referred to as “Sensei”. I have also heard that “Sensei” means “someone who has gone earlier”. This phrase, as I understand it, could mean “pioneer”.

In a martial arts context, a teacher is one who has more experience than the student. The experience is because that individual walked the path of learning that the student is just starting on. In this sense, the teacher was a pioneer on this path, as far as the student is concerned. This does not mean that the teacher is a pioneer who created a new martial art system, it just means that the teacher has traversed the path before the student and hence can guide the student on the same.

This leads to an interesting outcome. Since students walk the same “path” as a teacher, or learn in a manner similar to their Sensei, they become “similar to” their teacher in the way they move. This is a common occurrence. If a martial artist who knew the teacher saw just the student move, he or she would be able to tell who the student’s Sensei was.

This is how lineages get created in the martial arts. A lineage could lead to the development of a style or school (Ryu or Ryuha (plural)) or system of martial arts. The lineage could be specific to an extended family or to a region. An example of this is the “Togakure Ryu”, one of the 9 schools studied as part of the Bujinkan. The “Togakure” in the name is supposed to be in reference to a village in the Iga province of Japan.

The concept of a lineage extends beyond the martial arts, into other art forms and sports as well. Cricket is the most popular modern sport in India. There are 3 “schools” of batting recognized in India. These are the Bombay school, the Deccan school and the Delhi school. Each of these has produced great batters.

Similarly, in Hindustani music, in north India, we hear the term “Gharana”. A Gharana refers to a lineage. The word “Ghar” in modern day Hindi also means “home”. So, a Gharana could refer to a lineage literally, as it comes from a family in a home. But then, the Gharanas are associated with regions. Some examples are the Delhi Gharana, the Lucknow Gharana and the Benaras Gharana. As the names suggest, each of these is named after a region. This concept of lineage extends to architecture, painting, weaving, pottery and any number of other arts.

The festival of Guru Poornima is observed on the first full moon day (Poornima) of the month of Āshāda (coincides with a part of July). It is observed to mark the birth anniversary of Maharishi Veda Vyasa. Veda Vyasa is also called Krishna Dwaipāyana and Bādarāyana. He is truly the ultimate Guru! This is obvious once the corpus of knowledge that is attributed to him is recognized.

Veda Vyasa is most well known as the composer of the Mahabharata (or at least the Jaya, which is the core of the 3 nested dialogues which form the Mahabharata). He is also credited with compiling the Vedas into the form we know today (hence the word “Veda” in his name). The 18 Mahapuranas are also attributed to Veda Vyasa’s authorship or compilation. In other words, according to tradition, a large volume of texts from Hindu culture owes its existence to this greatest of Gurus!

That said, it is not just teachers of knowledge that are revered in Hindu culture. There are great Gurus for the martial arts as well. I will mention just four that are top of mind for me. There are several other great Gurus, from history and culture, all of whose stories I would strongly recommend everyone to visit.

The 4 Gurus who are top of mind for me, from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, are,

- Parashurāma

- Vishwāmitra

- Drona

- Balarama

The first 3 of the 4 mentioned above form a lineage of sorts. Let’s look at a few points about these great Gurus.

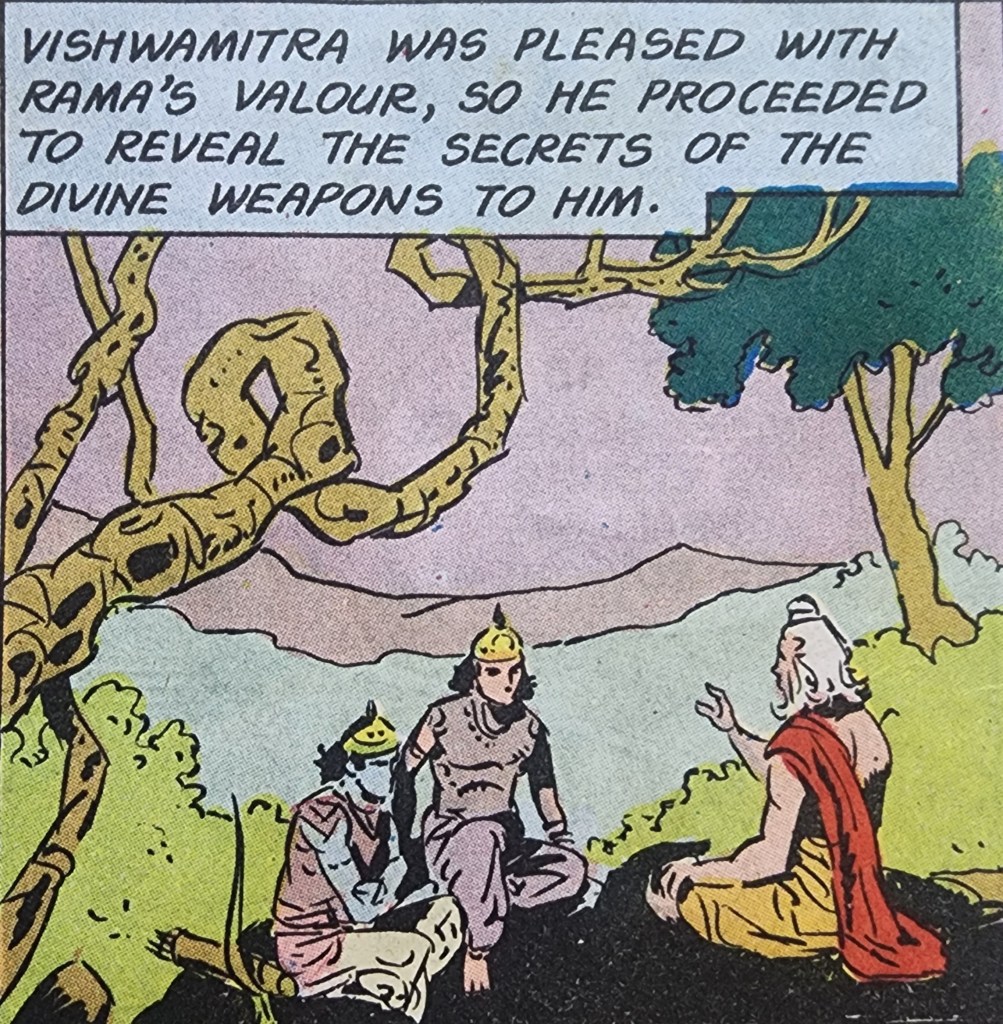

Brahmarishi Vishwāmitra imparts knowledge of celestial weaponry to Rama and Lakshmana. Image credit – “The Ramayana” published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Vishwāmitra was the Guru who was a martial arts instructor of Lord Rama. It was from Vishwāmitra that Lord Rama received a lot of the celestial weapons that he would use later. Vishwāmitra, before he became a Brahmarishi, was an egotistical king named Kaushika. Kaushika obtained powerful celestial weapons to use against Vasishta, who was Rama’s first Guru at Ayodhya! Of course, the weapons were of no use against Vasishta, but they were successfully used by Lord Rama, who was a student of both Vishwāmitra and Vasishta. Vishwāmitra of course had long overcome his rivalry with Vasishta by this time.

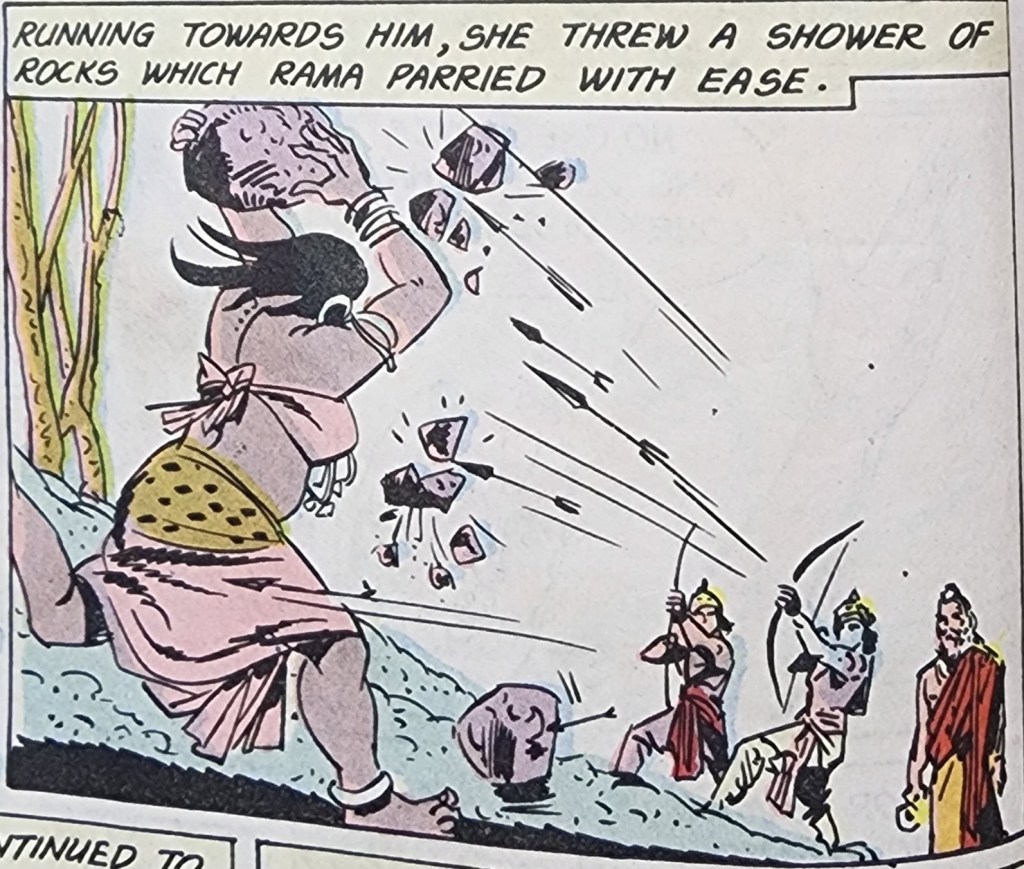

Brahmarishi Vishwāmitra guiding Rama & Lakshmana in their fight against Tataka. Image credit – “The Ramayana” published by Amar Chitra Katha.

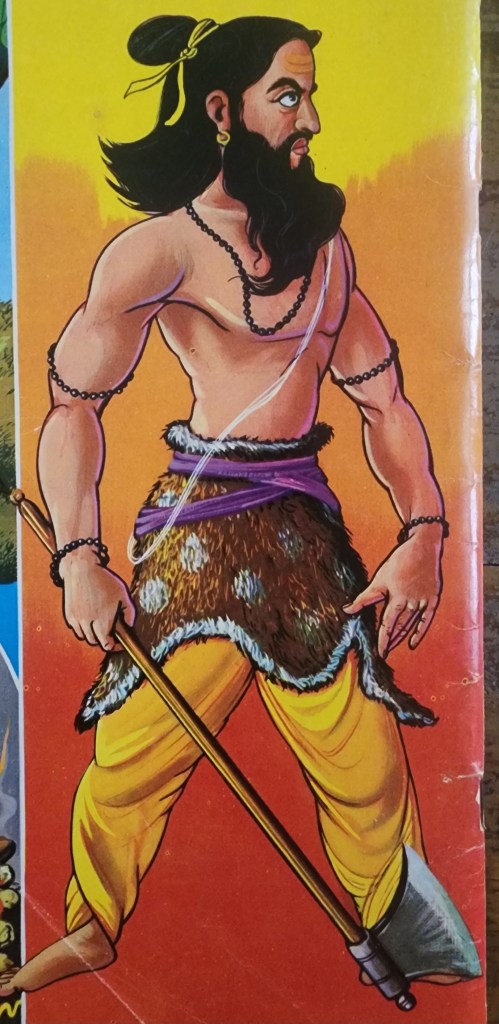

Parashurāma was Vishwāmitra’s grandnephew (the story of their birth is fantastic!). He was one of the greatest warriors of his time, of any time. He is also one of the 7 Chiranjeevis (immortals) who are supposedly still around during modern times, but not accessible to normal humans. Lord Parashurāma is the sixth avatāra of Lord Vishnu and the future Guru of Kalki, the tenth avatāra of Lord Vishnu expected to manifest in the future.

My favourite depiction of Lord Parashurāma. Image credit – “The Bhagavat for Children”, published by Anada Prakashan.

While Lord Parashurāma is best known for his mastery of the Parashu (axe), he was also a wielder of all celestial weapons. Parashurāma was the teacher of both Bheeshma and Karna, two of the greatest warriors who fought on the side of the Kauravas in the Kurukshetra War (the climactic war in the Mahabharata). He was also the Guru through whom Drona achieved his mastery of all weapons. Lord Parashurāma is someone whose legacy extends to modern India as well. He is considered the origin of the martial art of Kalari Payatt, which is famously practiced in the southern Indian state of Kerala!

Lord Parashurāma confronting Lord Rama early in the Ramayana. Image credit – “The Ramayana” published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Drona, also called Dronācharya was the teacher of most of the main characters who fought in the Kurukshetra War. The “Acharya” in his name is because he was a Guru to all the Kuru princes. Drona was also one of the warriors who was invincible. He was eventually killed by a trick, which forced him to drop his weapons and give up fighting. In this sense, he is the same as Bheeshma and Karna. Both of them were also warriors of such incredible prowess that the only way to defeat them was when they either chose to or could not fight!

Drona receiving knowledge of weaponry from Lord Parashurāma. Image credit – “The Mahabharata 05 – Enter Drona”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Based on the described prowess of Lord Rama, Vishwāmitra was a great Guru! His grandnephew Parashurāma was a God, whose students were among the greatest warriors ever, some being invincible. One of Parashurāma’s students, Drona, became a great Guru in his own right. So Parashurāma’s school was a dream for any martial artist! Considering he and Vishwāmitra are from the same family, they could be considered to be from the same lineage.

Drona being terror incarnate towards the Pandava army. Image credit – “The Mahabharata 36 – The Battle at Midnight”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

The last of the great martial Gurus I mentioned above is Balarama. He is the older brother of Lord Krishna. Balarama is considered an avatāra of Ādishesha, the serpent on whom Lord Vishnu rests. He was the greatest gada (mace) fighter ever. This was despite the weapon he is most associated with being the plough! He was the teacher to both Bheema and Duryodhana. Bheema and Duryodhana fought on opposite sides in the Kurukshetra War. Both Bheema and Duryodhana were disciples of Drona as well. They went to Balarama for specialized training in the mace (gada).

Balarama wielding the plough! Image credit – “The Mahabharata 39 – After the War”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Considering that all these Gurus were teachers of the martial arts, I suppose they could be considered Sensei as we understand the word today, specifically considering the lineage they were from and the one they perpetrated.

Balarama was the Guru for the Gada, for both Bheema and Duryodhana. Image credit – “The Mahabharta 38 – The Kurus Routed”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

We in India have a culture where a Guru, or a teacher is deeply respected and that comes from listening to stories passed down in our traditions. But the fact that some of these Gurus were martial arts teachers is not specifically recognized, even though it is well known. The word Sensei, in modern times is one that inspires great respect too, thanks to Japanese culture, where expertise, experience and teachers are deeply respected as well.

Looking at the two cultures, it should be possible to recognize that we always had many Sensei in India, who were Gurus of the martial arts. And they were as respected as a Guru from any other field of knowledge or expertise. The identification of this aspect was the purpose of this article. I hope I have been successful in highlighting the martial aspect of our culture and its extension to our respect for Gurus.

Notes:

* The many words for “teacher” according to the much forwarded WhatsApp message.

The teacher who gives you information is called Adhyapak.

The one who imparts knowledge combined with information is called: Upadhyaya.

The one who imparts skills is called Acharya.

The one who is able to give a deep insight into a subject is called Pandit.

The one who has a visionary view on a subject and teaches you to think in that manner is called Dhrishta.

The one who is able to awaken wisdom in you, leading you from darkness to light, is called Guru.

** Another word for teacher that many Indians know these days is “Sifu”, thanks to movie, “Kung Fu Panda” (2008).

Thoughts from Op Sindoor, Part 3 – Money matters!

India did not have a strong martial arts culture in the last few decades, until recently. Even now, it is not prevalent in all parts of the country. In places with higher disposable incomes, interest in and practice of the martial arts is growing. In parts of the country that have a strong continuation of historical traditions, martial arts are present as well, but more as a performance art. This is not true historically though. Martial arts were a vital part of Indian culture for many centuries before diminishing in importance in the latter half of the 19th century.

Now that martial arts are making a comeback, an interesting aspect is visible. There is a cost associated with practicing the martial arts. The costs include time, effort and money. Financial costs include, tuition fees of teachers, membership fees of gyms or dojos, cost of apparel and training equipment*. Training equipment includes protective gear and training tools, which include practice weapons. Beyond this, time is spent in traveling to the place of practice and in practice itself. And then there is the effort that it takes to make time and financial resources available for martial arts practice.

The costs mentioned above were present in the past as well. For some professions, this cost was valid as it directly impacted the earning of a livelihood. This is true in modern times as well. But for individuals who are not working with law enforcement, first responders and the defence services, this cost is not necessary. The payback is not necessarily monetary. Hence, there comes a point when martial arts practice becomes discouragingly costly. This was true in the past and is true in contemporary times as well.

The cost of martial practice extends to nations too. Here the cost is justified as a nation’s sovereignty and territorial integrity are dependent on the expenditure on its martial wings, in other words, defence forces, intelligence agencies and law enforcement services. As this is vital at a national level, all nations have defence budgets.

But the defence budgets of all nations are not the same. The defence budget of the USA is almost a trillion USD! The defence budget of China is about 350 billion USD. The defence budget of India is 78 billion USD (in 2025). The cost of defence preparedness might be the defence budget but that is not the same as the cost of war.

The cost of war, depending on how long it lasted and the devastation it caused can be varying. The cost in terms of loss of life and limb of citizens is incalculable. It renders a section of the population unable to participate in any economic activity and in many cases dependent on the state, which is a necessary drain on the economy. There is also a cost associated with reconstruction and rebuilding of the economy. This is exclusive of the opportunity cost and the uncertainty of real recovery.

Unlike the cost of war, defence preparedness can have a positive effect. Over time, increasing defence budgets can lead to the creation of a military-industrial-academic complex. This complex leads to better education for large sections of a society and development of a manufacturing ecosystem. This leads to more jobs, development of advanced technologies and improved innovative abilities of a society. Defence preparedness also involves having great infrastructure in perpetuity. And then there is the boost to the economy through the export of weapons and weapon systems. All this is without even considering the benefits of the development of dual use technologies. Beyond all this there is the saying “If you want to have peace, prepare for war” (from the original Latin, “Si vis pacem, para bellum”).

It could perhaps be said that preparation for war can lead to restarting and rebuilding of a flagging or destroyed economy. A perfect example of this is the Ashwamedha Yajna in the Mahabharata, which occurs years after the end of the Kurukshetra War. The reason the epic gives for the event is that Yudishtira performs this yajna to atone for the sins committed during the Kurukshetra war. But I opine that the reason for this yajna was to kick-start the economy of the kingdoms of Hastinapura and Indraprastha.

A very large number of males had died in the Kurukshetra war. If the numbers from tradition are considered, somewhere between 3 and 4.5 million men died in the war. This meant that a large part of the working population in Northern India was dead. The coffers of all the kingdoms that participated in the war were empty due to the logistics of the war. This meant that the economy of all the participants was in the doldrums.

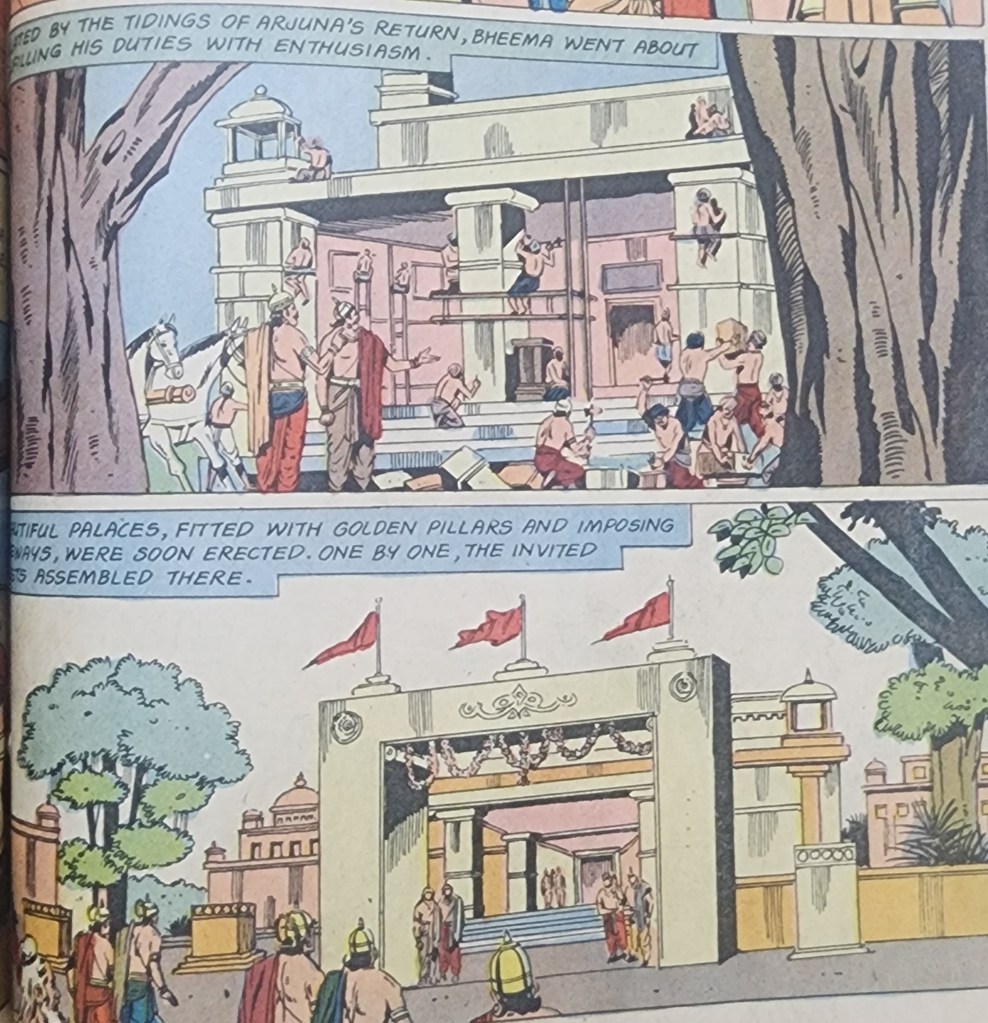

The Ashwamedha Yajna requires a large investment to perform and conclude successfully. To start with, a large quantity of gold is needed in the performance of various rituals and all the participating Brahmanas have to be compensated for their part in the yajna. A strong army is needed to protect the horse, the Ashwa of the yajna.

The economy does not allow for an Ashwamedha Yajna. Image credit – “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

The horse would wander around for a year in various kingdoms. These kingdoms could stop the horse or let it pass through. If they let it pass through, they had to offer tribute or sign a treaty with the army of the king whose horse it was. If they stopped the horse, they kingdom that stopped the horse had to fight the army protecting it. The fact that an army was involved meant that a functioning supply chain was needed, apart from soldiers and their training.

The massive logistics effort needed for the Yajna. Credit for the images- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

So, all parts of the economy have to contribute to the Ashwamedha Yajna. Food production is needed to feed the army. Industry is needed to equip the army and carry out the yajna itself. Administrative and financial bureaucracies have to be put in place to coordinate the logistics of all the activities. With all this coming up, the economy gets a jolt to restart. The tribute from the successful performance of the yajna ensures capital flows for growing the economy further.

A strong military is needed and military conflict is inevitable during the Ashwanedha Yajna. Credit for the images- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

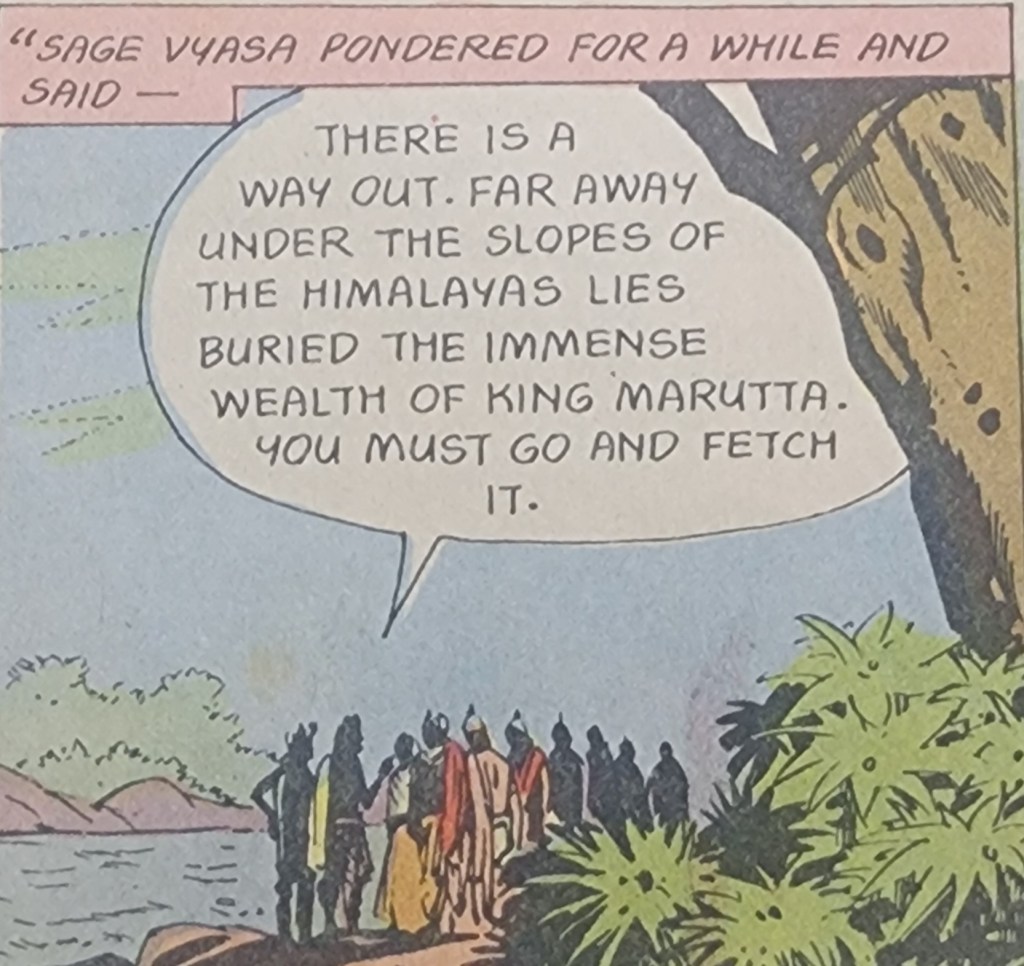

But, for a faltering/failed economy to be able to do this, an initial capital infusion is needed. This could be a loan. But in the Mahabharata, there was no institution or fellow kingdom that could afford to hand out a loan post the Kurukshetra War. So, the Pandavas dug up buried treasure. Maharishi Veda Vyasa directed them to the treasure. The treasure, a vast hoard of gold became the seed capital for the Ashwamedha Yajna and the prosperity it eventually led to.

Buried treasure is initial investment! Credit for the images- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

This wonderful segment of the Mahabharata shows how preparation for a war could lead to economic recovery. But the Kurukshetra war itself caused untold devastation. The epic is in this sense a wonderful case study for both war and its consequences and the economic recovery preparation for war can lead to (even if the defence preparedness is disguised in a sacred yajna).

Thus, it has always been about availability of resources for martial preparedness, and martial preparedness to protect and enhance economic resources and their availability. But, and it is a BIG but, this only holds where there is a democratic or a Dharmic society. A Dharmic society as I am referring to the word, is one that is defined by a clear understanding of responsibilities of the administration, even if the head of government is a king or queen who holds power due to heredity.

Wealth distribution is a must during and after the Yajna. Image credit- “The Mahabharata, Part 41 – The Ashwamedha Yajna”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

Defence preparedness is unlikely to function in the case of Palace Economies. A palace economy is one where the leader or king or dictator or the family of the same, controls all resources and distribution of the same. This control could be arbitrary, based on the will of the leadership, with no link to real world performance, hardships, challenges or threats.

A fantastic example of a palace economy is the Delhi Sultanate in India, specifically under the Mamluk dynasty and the Khaljis. All the Turkic invasions of Northern India were by palace economies. From the little history we were taught, there was no doctrine of administration that these invaders followed.

After the fall of the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughals controlled the regions of Punjab. The later Mughals, after the death of Aurangzeb, struggled to defend this region. When Ahmed Shah Abdali of the Durrani Empire centred in modern day Afghanistan invaded Punjab repeatedly, they were unable to protect the populace of this region.

Abdali was a wonderful example of a palace economy as well. He took over the regions of Afghanistan after the death of Nadir Shah of Persia, under whom he had previously served. The later Mughals were also a palace economy, but with a much smaller resource pool to go around. Abdali, on the other hand, invaded Punjab and northern India several times to acquire wealth, which was then distributed as he desired, further strengthening his palace economy. The invasions of Northern India continued until 1761 and the 3rd battle of Panipat and the invasions of Punjab continued for a few years even after that seminal event.

Abdali won the 3rd battle of Panipat, but the cost of the victory dissuaded him from ever returning to the plains of Northern India. His ravaging of Punjab is chillingly captured in the following Punjabi saying. “Khada peeta lahe da, baki Ahmed Shahe da”. It means that only what one has eaten and drunk is one’s own, the rest belongs to Abdali. It refers to the loot that ensued when Abdali attacked; people lost everything. And this kind of loot was important to keep a palace economy functioning.

The lack of this functioning in the later Mughal court required the Marathas to fight the 3rd battle of Panipat. Though they lost the battle, they successfully diminished further Afghan invasions. All further battles between Indians and the Afghans, beyond Punjab, occurred when Afghanistan was invaded by the East India Company or the British Raj. By this time, the Afghan palace economy had faltered and become dysfunctional as well. This is classic of nations where economic development did not kick off in the early modern era.

There is however a trap of exhausting one’s economy with an excessive focus on defence preparedness. I have heard a lot of people say that the USA defeated the USSR by outspending them on defence. The USSR failed economically and could not keep up with the USA. In the quest to keep itself on par with the US in defence spending, the USSR bankrupted itself.

Economic growth and development are a vital part of being able to spend on defence. The overall economy of a nation must grow continuously. When this happens, a part of the growth can benefit the defence budget. If the economy does not grow, but the defence budget keeps increasing, the country eventually ends up being a basket case. This focus on overall economic development is the reason the Ashwamedha Yajna ends up rejuvenating the national economy, because it focuses on supply chain as a whole and not just on the armed forces.

In the modern Indian context, we Indians have a threat on two fronts. Pakistan on one and China on the other. Pakistan is gradually becoming a client state of China and is being used by the latter to prevent India from becoming a competitor on the global stage for various resources. The events in Galwan in 2020 and in Pahalgam in 2025 clearly reveal that ignoring the threats will not make them go away. India will have to always be ready to militarily confront the twin threats. I include threats in the cyber and space domains when I use the term “military” here.

So, increasing defence spending is a foregone national imperative for perhaps the coming decade. This is likely what both adversaries want, to slow down India’s economic growth. China is banking on what was mentioned in my previous post, make the Indians fight themselves to keep them occupied and weakened – Pakistanis are Indians by a different name, remember**?

Will their expectation of a weaker India come to pass? Will this spending take us the way of the USSR or make our economy grow faster and become more robust? This is a question the answer to which will only become apparent in maybe 10 or 15 years. If we go about only importing technology and weapon systems, we could go either way. But if an academic, industrial military complex is developed locally, we could become a far greater economy with a stronger military and overall national power.

Notes:

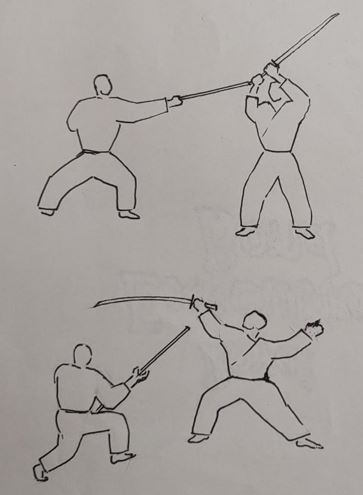

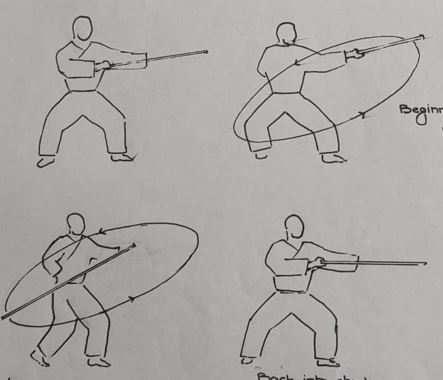

* Let me elaborate with an example. We needed training katana for practice at the dojo. We could by them online, in a sports store, get a carpenter to make it or make training katanas ourselves. Back in the middle of the 2000s, an online purchase or a purchase at a sports store was out of the question. E-commerce was just beginning for only books and sports stores did not stock much martial arts equipment other than karate and taekwondo apparel and training pads. Getting a carpenter meant having a sample to go by. All of this had one serious impediment, MONEY. We did not have disposable incomes to consider this purchase lightly. We had to seriously consider if we would train the martial arts for years to come, to consider the investment feasible. Chances of continuing were always small, so the investment was unlikely as well.

That left the option of making our own training katanas. This was done with building scrap available at home, mainly small diameter PVC pipes, which were wrapped with fabric tape and held together with cellophane or insulation tape. The hardest things to make were the scabbard or saya of the sword and the tsuba or disc guard on the katana. Because these were difficult to make, the saya was given a skip and the tsuba was a piece of thermocol (polystyrene). These worked to an extent.

The drawback with the handmade equipment was twofold. The lack of a saya meant that any technique that required the drawing of a sword could never be accurately practiced. It was always an approximation. The flimsy tsuba came apart often and that led to either injured fists or to a lack of understanding of how to use the tsuba to lock the opponent’s position. So, there was pain and poor training. Both these were due to a lack of financial resources.

Our teacher back then had said that in the past, good weapons were expensive and the same was true in contemporary times as well. This was a lesson well learnt. It was as clear an elucidation of the importance of money in martial arts as any. Money leads to technology and training and both improve chances of survival.

** https://mundanebudo.com/2025/06/19/thoughts-from-op-sindoor-part-2-nothing-has-changed/

Bhrāmari Devi, Bees and Martial Arts

20th May was “World Bee Day”. In India, Bhrāmari Devi is a form of the Devi, the Female Principle or Goddess, worshipped in many forms. “Bhramara” means a bee in some Indian languages. So, Bhrāmari Devi is the Goddess of Bees or Goddess with attributes of bees. Like with all forms of Gods and Goddesses, Bhrāmari Devi is also credited with slaying an Asura who had upended the natural order and thrown the doors open to chaos. And this brings the aspects of martial arts into the story which I shall explore further in this post.

The Asura Aruna like many other Asuras gained a boon (vara) from Lord Brahma. According to the boon, he could not be defeated or killed by any creature that was a biped or a quadruped or a combination of the two. This meant that he was invulnerable to all humans, Gods, Goddesses, other humanoid entities and also the large beasts that could harm most humans as we understand them now. This boon seems to be one that compensated for the Varāha and Narasimha avatāras. Varāha was a boar and Narasimha was a combination of man and lion.

I am making one assumption about this boon. If a biped, in other words Devatas, Mānavas (humans), Vānaras, Rkshyas (Jambavan’s kind – sometimes written as Rikshyas) and the like are prevented by the boon from killing Arunāsura, that includes any weapons wielded or discharged by them. So, a human shooting an arrow at the asura would not kill Arunāsura, nor would a warrior wielding a sword. If this was a boon in modern times, a bullet or missile fired by humans would not kill Arunāsura, nor would an AI system with human programming or input.

With this boon, Arunāsura dominated the three worlds and threw natural phenomena, the guardians of which were the Devas, into chaos. This required that he be stopped, even if it meant killing him. Since no weapon or massive beast of prey would have any success, other options needed to be explored. This is where bees and Devi Bhrāmari help resolve the problem.

Bhrāmari Devi, image credit – Wikipedia

Devi Bhrāmari unleashed a swarm of bees that stung Arunāsura. The Asura’s own attacks against the Devi were successfully defended by her. Arunāsura could not fight the bees. He eventually succumbed to the venom in the bee stings. The boon held and Arunāsura was defeated and killed by Hexapeds (creatures that walk on 6 legs), not bipeds or quadrupeds! Also, the mighty Asura was laid low by insects, among the smallest of creatures!

It is possible that Arunāsura did not include insects and other hexapods in his request for the boon since he did not consider them a threat to worry about. In this sense, a lack of awareness or incomplete threat perception did him in. He “expected” insects to not be a threat! This was an assumption, and in a conflict, assumptions and expectations are dangerous things.

I have heard a joke that has been around for at least a few decades now. A few Japanese swordsmen are competing to determine who among them is the best. The contest is to cut a fly! This joke works because everyone realizes that a sword is not what one fights a fly with. It is extremely difficult to hurt a fly with a sword. This fact holds true for bees as well!

There is a proverb I have heard, “You cannot fight smoke with a sword”. This aptly explains the situation anyone faces against a swarm of bees. When one is attacked by a swarm, all creatures know that getting away is the only option, one cannot stand and fight the swarm, unless one specifically came prepared for that eventuality. The fact that Arunāsura did not include protection from insects in his boon, shows that he was not prepared for this attack at all.

From what I know, it takes a couple of thousand or more stings to kill an adult human. Of course, if one is allergic to the venom, the number required is a lot lower. Considering we are currently in the “year of the snake”, it is apt that we are discussing a story where venom is the weapon! Venom is poisonous and fatal when injected beyond certain doses. In the case of Arunāsura, thousands of bees would have injected small doses, the sum of which was sufficient to kill him. It is a case of applying a large quantity of small solutions to a very big problem (the world ending kind!). It is the natural world equivalent of the classic adage “death by a thousand cuts”.

The story of Arunāsura is one in a long line where natural phenomena and animals are used to defeat threats to the natural order/humans and the Devatas. The stories of Varāha, the boar and Narasimha, the man-lion are well known. Another story that is pretty well known is when King Pareekshith was killed by the bite of a venomous snake. A less well-known story is Indra murdering a meditating asura by the name of Karambha. Indra committed this murder in the form of a crocodile. Indra paid for this subterfuge and assault on an innocent victim (Indra was worried that the meditation would lead to a boon which could make Karambha a threat to him in the future – a “Minority Report” kind of “pre-crime” situation).

A more interesting story of using a natural phenomenon as a weapon is that of Namuci and Indra. Namuci was an Asura of great renown and an enemy of Indra, the king of the Devas. Indra had promised Namuci that he would not attempt to kill him with anything that was either wet or dry. This seemed like a fair promise. But Indra smothered Namuci with foam on a seashore. Foam, supposedly being neither wet nor dry, allowed him to kill Namuci without breaking his promise. Indra had to face the consequences of his treachery of course.

In Hindu tradition, we celebrate a festival called “Āyudha Pooja”. This festival is celebrated on the ninth day of the 10-day long Dasara (Dussehra) festival. On this day, various tools of various trades are cleaned and receive gratitude from their users, for aiding them in living a good life. The tools that are worthy of respect in this festival include agricultural implements, weapons of war, machines in industries and even the laptops we use in the service sector.

The term “āyudha” means weapon. But it also means “tool”. Any tool that aids in life is an “āyudha”. Weapons are just tools that are used in war or any physical fight/conflict. And of course, in many cultures around the world, agricultural tools have doubled up as weapons on several occasions in history. A great example of this in Hindu culture is Balarama, the elder brother of Lord Krishna. The weapon associated with Balarama is the plough, which is most definitely an agricultural implement.

Animals have been used as tools and also as weapons of war for ages. Elephants, horses, pigeons and dogs are well known to have been used in war. If conspiracy theories are considered, even dolphins and chimps have been used as potential weapons in the 20th century, during the cold war and the 2nd world war before that. The story of Bhrāmari Devi is just an extension of this well-known teaming of humans and animals during times of conflict.

Honey Bee, image credit – Wikipedia

One instance of an animal being a tool to end a war while NOT being a weapon is the story of how Lord Muruga/Skanda/Karthikeya came to have the peacock as his vāhana. Vāhana can be translated as “vehicle” or “mount”. Most Gods we Hindus revere have animal companions, most of whom are vāhanas. The vāhana of Lord Muruga is the peacock.

Lord Muruga defeated and killed the Asura Tāraka. He also defeated another asura named Surapadman. I have heard in some stories that Surapadman is the younger brother of Tārakāsura. Surapadman eventually surrendered to Muruga. He asked for forgiveness and wanted to make amends for the harm he had caused. In return for his surrender, Lord Muruga spared his life. Surapadman then became a peacock and would serve Muruga as his vāhana. The peacock in this case is more like a peace treaty which led to the end of a war. Here, the peacock is not a weapon, but a tool, which led to peace.

This same aspect is true for bees in reality as well. That bees can kill is well known. I remember reading an article in the Reader’s Digest in the early 90s, which featured an attack by a swarm of bees. It was part of the magazine’s “Drama in real life” segment. That was the first time I read of a situation where an individual’s life was at risk due to an attack by bees. Even though we knew that bees and wasps are potentially dangerous, this article brought home to me the threat to life that they can pose. A similar article was also available in the same magazine, more recently, in 2021. I am sharing the link to that article in the notes below*.

Despite the threat bees pose, they are widely respected in the modern world. They are well known for the vital role they play in the ecosystems they inhabit and also for the wealth they can generate. The pollination services bees provide make them a keystone species in the ecosystems they have evolved to inhabit. Similarly, honey and beeswax are both sources of income for people around the world. Beeswax is used in cosmetics and honey as most would know has some medicinal properties.

Bees deploy chemical weaponry, in the form of the venom from their stings. The same biochemical abilities of the bees, results in the beeswax for the hives they build and for the honey, that is created from the nectar of flowers they visit.

I must mention a few pop culture references that come to mind due to this article. The point about bees being extremely useful and vital to the environment while being capable of threatening life has a hilarious parallel in the movie “Ninja” (2009). The movie stars Scott Adkins who is a great martial artist. The move itself is a fun watch. In the movie, the hero’s girlfriend is poisoned. The hero has inherited a katana from his teacher. The hilt of the katana has a secret chamber which has the antidote to the poison killing his girlfriend! He uses it to save her, and the antidote in the vial is the exact quantity needed to save her life! 😊

The hero does not know that there is a vial of antidote hidden in the structure of the sword until his girlfriend is poisoned. One of the teachings he has received from his teacher is that the katana of the ninja can take a life and also save a life. The hero recalls this teaching at the end and realizes that the teaching was literal! He then deduces that the antidote must be hidden in the sword! 😀 The whole scenario reeks of plot armour for the girlfriend!

The other reference has wasps** as the stars and not bees. But I am including it here since wasps are close relatives of bees and the scenario is far too amazing to ignore. There is a novel called “The Impossible Virgin” be Peter O’Donnel. It is one of the novels by the author in a series that stars the character “Modesty Blaise”. Modesty Blaise appears in 11 novels, 2 short story collections and 96 stories that appeared as newspaper comic strips.

Modesty Blaise and her friend Willie Garvin are extremely competent individuals. And they are both extraordinary martial artists with skills in unarmed combat and proficiency in many weapons, both historical and modern. In the novel “The Impossible Virgin”, they face off against a large number of gangsters while being outnumbered. This fight happens in a valley called “The Impossible Virgin” as people avoid entering it. Yes, the name is corny by modern standards, but the novel was published in 1971.

The Modesty Blaise novel, “The Impossible Virgin”, authored by Peter O”Donnel, published in 1971

Modesty and Willie are stuck without firearms against opponents who are carrying guns. But their opponents cannot use guns due to the valley. The valley is home to hundreds of active wasp nests. The sound of any gunshot will echo across the valley and trigger the wasps to attack. So, the fight is now against the machetes carried by the gangsters. Modesty and Willie use quarterstaffs to fight and defeat the gang. Fighting with a quarterstaff is basically bojutsu as we practice it in the Bujinkan system of martial arts. The sequence of bojutsu in the book is wonderful. And the reason for fighting with a staff is the presence of the wasps! The insects here are a shield without intending to be so! 😊

I included this sequence here since the wasps are responsible for some wonderful bojutsu action. But the sequence reminds us of another martial aspect of bees. Bees are quite militaristic! They have various roles and specialize in their tasks, just as modern militaries with high technology have specialists for different roles. And in conclusion I must add, a swarm of bees sounds a lot like a modern-day drone, at least the ones used by photographers at weddings and other ceremonies. So, perhaps quadcopters and similar military drones also sound like a swarm of bees on the attack! 😛

Notes:

* https://www.readersdigest.in/true-stories/story-a-thousand-stings-127356

** “World Wasp Day” is on 24th September

Lord Narasimha – A treasure trove of martial concepts

Narasimha Jayanthi was on the 11th of May this year (2025). Lord Narasimha was the 4th of the Dashāvatāra (dasha – 10, avatāra – incarnation). Lord Narasimha is a representation of incredible martial prowess. It is this prowess that I delve into in this article, to identify how his abilities are still practiced in real world martial arts, which in turn almost always have real life applications beyond the dojo.

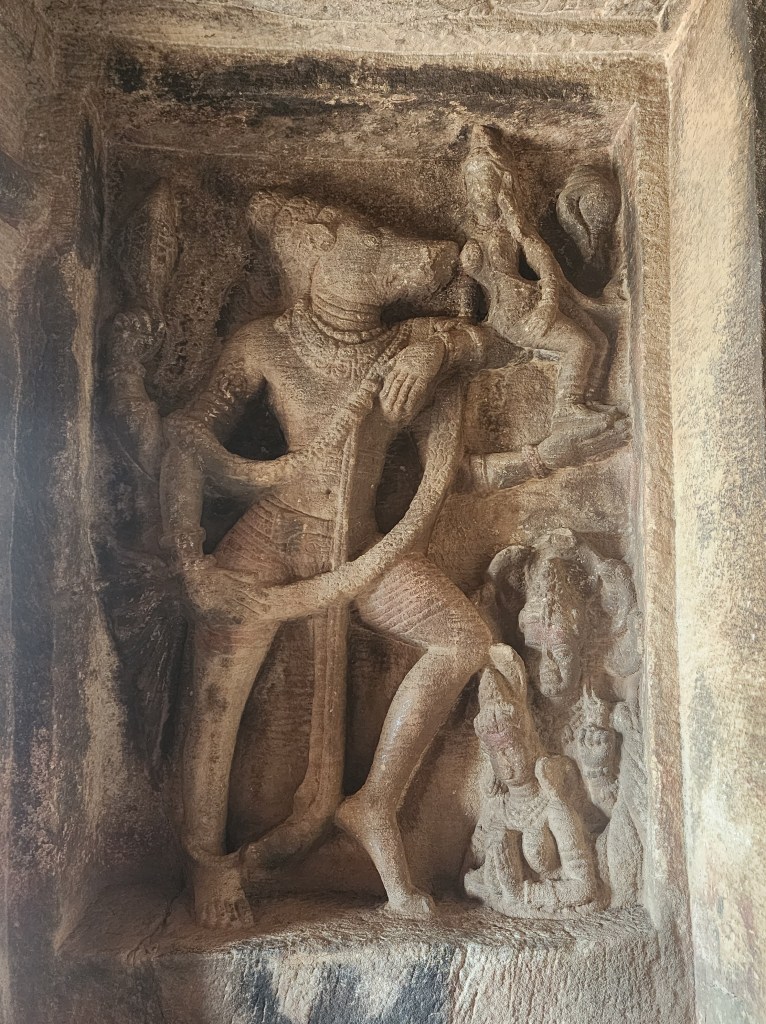

A depiction of Lord Narasimha from the 6th century CE, Badami, Karnataka, India

Lord Narasimha came to be, to specifically counter one Asura, Hiranyakashipu. Hiranyakashipu had a vara (boon) from Lord Brahma which made him impossible to kill and thus functionally immortal. Hiranyakashipu’s boon conferred the following protections on him.

- He could not be killed by a human or a beast

- He could not be killed during the day or during the night

- He could not be killed indoors or outdoors

I am now going to extrapolate a bit. I presume that Hiranyakashipu could not be killed by any weapon wielded by or controlled by a human. Otherwise, arrows would have been able to kill him in an age before gunpowder, an age when there existed “celestial weapons”, or astras of various kinds which could wreak unimaginable damage. Further, we will have to overlook the notion that humans are also beasts, just a different species. I have no idea if the boon took into consideration some specific definition for “human”.

I also presume that he was invulnerable to diseases that were cause by any biological vector, for they would constitute beasts. Considering the protection from the first point, the subsequent 2 points seem like an add-on package in case someone found a loophole in the first one. And as was the case, that is exactly what happened.

Beyond the boon itself, Hiranyakashipu was an incredible warrior, on par with the Devas. He wanted to be on par with Lord Vishnu before going out and conquering the world! This was the motivation for his gaining the boons. Further, he forced people in the lands he conquered to worship him instead of Vishnu. When I say worship, I mean in offerings at pooja, yajna and homa that are performed. There is a lot more nuance to every aspect of this story, which I cannot go into in this article*. I strongly recommend that everyone read the story in detail. Not only is it incredibly entertaining, but it is also full of conundrums and ways of overcoming the same. The connections to various happenings around the world is simply fantastic.

A common depiction of Lord Narasimha and his slaying of Hiranyakashipu in modern times. Image credit – “Prahlad”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

In the end, Vishnu incarnates as Lord Narasimha to destroy Hiranyakashipu. He bursts forth from a large pillar and fights Hiranyakashipu, eventually slaying him. There is a great fight between Hiranyakashipu and Narasimha, at the end of which Hiranyakashipu is disembowelled on the threshold. The end occurs by circumventing each aspect of the boon protecting Hiranyakashipu. These are as mentioned below.

- Narasimha was neither man nor animal, but both. Hence Hiranyakashipu’s boon did not protect him from Narasimha. Nara means “man” and Simha means “lion”, literally “Man-Lion”.

- Narasimha fought and killed Hiranyakashipu at twilight, which is neither day not night.

- Narasimha killed Hiranyakashipu on the threshold, which is neither inside nor outside. I do not know if the threshold was that of his throne room or that of his palace.

From all the iconography I have seen of Lord Narasimha, he used no weapons other than his claws while fighting the mighty Hiranyakashipu. The same were used to disembowel and kill the Asura king. This same pattern is seen even in modern days comics depicting the story of the Narasimha avatāra. At the same time, Hiranyakashipu is depicted as using a sword or mace (gada), sometimes a sword along with a shield. I must add, I guess that the claws of Lord Narasimha were exempt from being classified as a weapon as Narasimha was neither man nor beast.

Lord Narasimha fighting Hiranyakashipu who wields a mace and a sword. Image credit – “Dasha Avatar”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

I will now extrapolate again. Based on the way the fight between Lord Narasimha and Hiranyakashipu is depicted, I think of this as a fight between a great warrior who was wielding weapons and another warrior, who was fighting unarmed. Of course, the fact that Lord Narasimha is a God evens out the odds of going up unarmed against an armed warrior. And the fact that a God had to fight at all and needed weapons (!) shows the martial prowess of Hiranyakashipu.

Now that the details of the fight are clear, let me look at the aspects of the same which, while fantastic, can highlight aspects of real-world martial arts and conflict management.

I will start with the simplest and most obvious one. The use of claws. In the Bujinkan system of martials, among the historical weapons we learn of, there are two interesting ones, which are worn on the fingertips. One is called the “Nekote” and another is the “Kanite”. Nekote means “cat claws” and Kanite means “crab claws”. Visually, to me at least, the two seem very similar.