The previous two articles I posted were related to the festival of Deepāvali and the stories of the Dashāvatāra respectively. The article related to Deepavali was related to the stories about Naraka Chaturdashi and Bali Pādyami. In both the articles I identified concepts from the martial arts in the stories related to the festivals and the Dashāvatāra, and expanded on those. This article is an addition to those two and perhaps the last in the series, where I will try and delve into the last few concepts originating from the first article. A link is seen in the notes below to the two previous articles*.

In the previous article the main concept that I explored was “Issho Khemi”. “Issho Khemi”, based on my experience, was translated as either, “do whatever is necessary” or “do just enough”. Further, I referred to the biography of sword master Yamaoka Tesshu and his way of training the sword, to understand this concept. The biography of Yamaoka Tesshu referred to was ““The Sword of No-Sword: Life of the Master Warrior Tesshu”. I remember the book saying that Tesshu encouraged his students to train hard but did not focus on specific techniques or forms. In other words, in my opinion, he preferred that his students train the sword to use “Issho Khemi”.

Considering that we are referring to swords and doing whatever needs to be done, we need to consider another concept that I have learnt as part of the Bujinkan system of martial arts. This is the concept of “Katsujiken and Satsujiken”. Katsujikan means “the life-taking sword” and Satsujiken means “the life-saving sword”. Simply put, if the sword can be used to do whatever is necessary, the necessity could be, as the situation calls for, to save a life or take a life – Issho Khemi.

There are many ways of understanding “Katsujiken and Satsujiken”. The context in which it is used in reference to a real fight is “if you are not ready to kill, do not draw the sword”. This notion is not unique to Japanese martial arts. I have heard it said with respect to guns as well, where it is said that one should not draw the gun if one is not willing (or ready) to pull the trigger. There is a similar saying with Kalari Payattu as well. Kalari Payattu is the martial art form originating in the state of Kerala.

In Kalari Payattu, there is a saying which goes, “Thodaade Thodaade, thottaal vidaade”. It translates to “do not touch, do not touch; if someone else touches, do not spare that person”. Of course, what is being said is, avoid physical contact in a conflict, but if it is initiated by someone else and there is no choice but to fight, do not spare the other person (opponent). I am sharing a link in the notes below where a Gurukkal (teacher), Dr. S Mahesh, teacher and practitioner of Kalari Payattu makes this statement and explains the same**.

In this context, avoiding the drawing of the blade is one saving the life of the opponent. The objective is to avoid any injury to anyone. So, the sword is not drawn, hoping the situation can be deescalated. To this end, there are forms and techniques that are trained in the Bujinkan system of martial arts where one defends oneself with the sheathed sword. This sometimes looks like forms trained with the hanbo (3 foot staff). This then goes on to forms where the opponent is controlled without drawing the blade completely. The blade is partially unsheathed when necessary to ensure that the opponent realizes that pressing the attack further is detrimental to her or his health and the defender is offering an opportunity to disengage and end the attack. The blade is also sheathed as soon as this message is complete to avoid any escalation. Thus, without drawing the blade (completely), the lives of the attacker(s) and defender are saved. Thus, Satsujiken, the life-saving sword, is achieved.

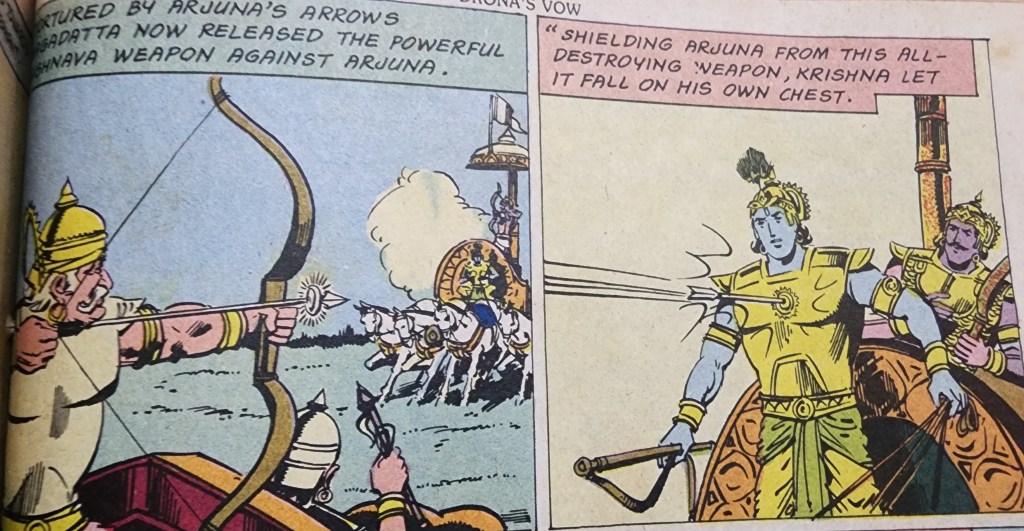

In case the situation is too far gone and there is no hope of surviving a physical conflict without incapacitating the opponent(s), Katsujiken has to be adhered to. Of course, it does not mean that anyone needs to lose their life. It means causing injury to the attacker(s) is acceptable to survive the physical conflict. Here, to save one’s own life, the life of another might have to be taken; at least physical harm may be caused to someone else. The imperative to cause injury to others might be more urgent when the safety or others is involved. If someone or something being attacked is dear to someone, that person might have to resort to the life-taking sword to save the others, especially if the individuals being attacked cannot escape or do not know how to survive without help.

When a situation calls for Katsujiken, one really needs to let go of thoughts of consequences of causing harm to others and focus on survival. This means being in the moment and doing whatever it takes to survive, with no motivations regarding the future. If one is lucky, this attitude might deescalate a situation and mitigate the need for Katsujiken (if the opponent is wise enough to sense the same).

Of course, it is never really clear when Katsujiken or Satsujiken have to be used. The choice might move from one to the other and depends entirely on the gut feel of the individual(s) involved in the situation at a given time and space. A change in the time, space or people will alter the consequences. Apart from this, hindsight might show what was possibly a better choice, but that is not much use except as experience for a future conflict.

Everyone hopes that Katsujiken is never needed. Satsujiken itself should be a last resort. This is possible with external factors like societal norms and behaviour. Another important aspect that prevents anyone from even considering Katsujiken is the efficiency and effectiveness of the legal and justice system of a place. The effort and negative consequences of having to deal with the legal system itself is huge motivator for people to avoid escalating a conflict to physical levels and then to a case where bodily harm is caused. The punishments one faces for physical harm to others are a deterrent to any life-taking of even injurious actions. This of course, is only possible if the individuals involved in the conflict cannot act with impunity, which means they are not afraid of the legal or other consequences of their violent actions.

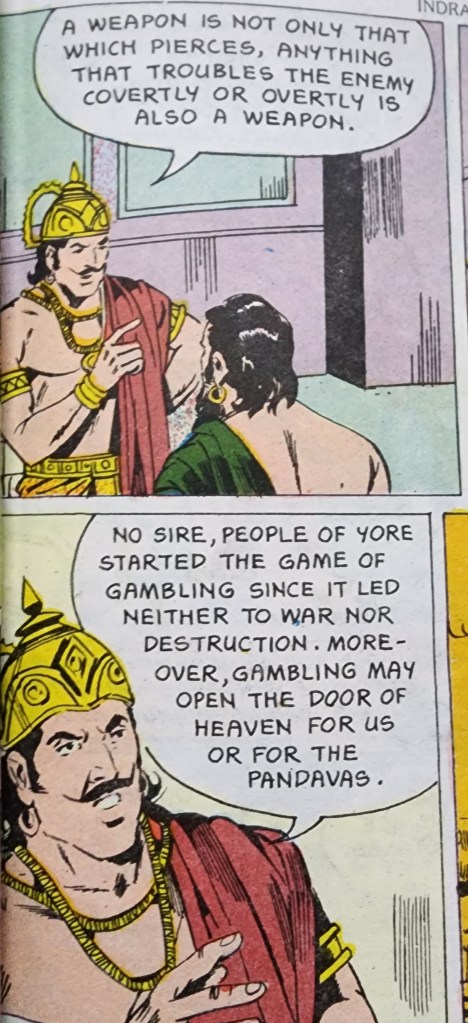

Even though Katsujiken and Satsujiken have “ken” at the end which represents a sword, the concept is not restricted to swords. The life-saving and life-taking aspect is with relation to any weapon or even unarmed conflicts. It could perhaps even be expanded to violence which is emotional or intellectual (consider gaslighting, ragging/hazing, demeaning narratives, and the like).

In a previous article where I discussed the festival of Āyudha Pooja, I had mentioned that the word “Āyudha” means weapon. But based on the manner in which the festival is celebrated, “Āyudha” can be any tool. A link to the article where this is discussed in detail is seen in the notes below.+ Based on the previous paragraph and the Āyudha Pooja festival, where any tool can be considered a weapon and vice versa, the life-taking and life-saving nature can be attributed to any concept (idea or theory included) or tool applied as a solution in a conflict.

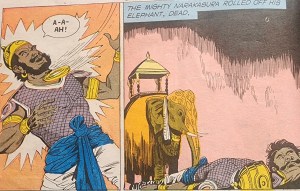

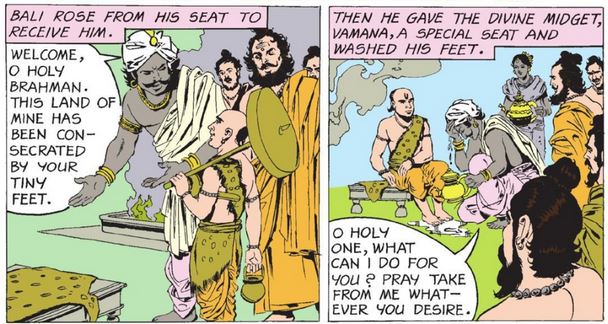

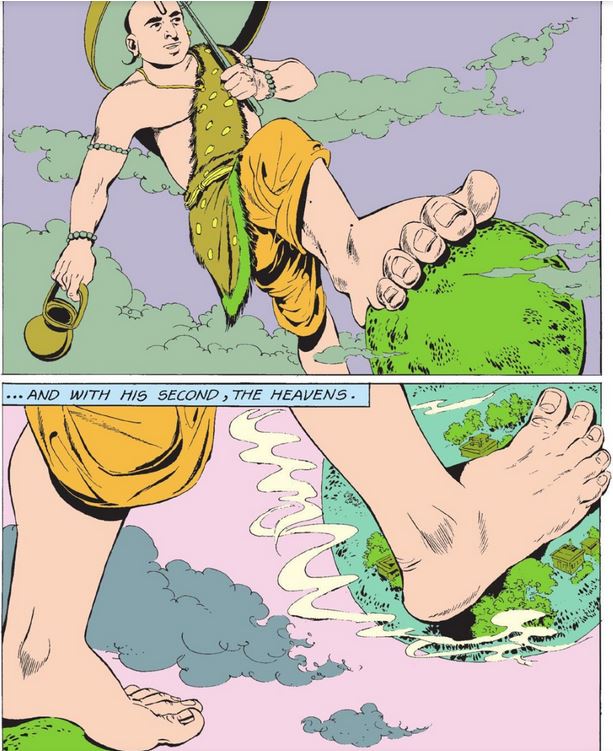

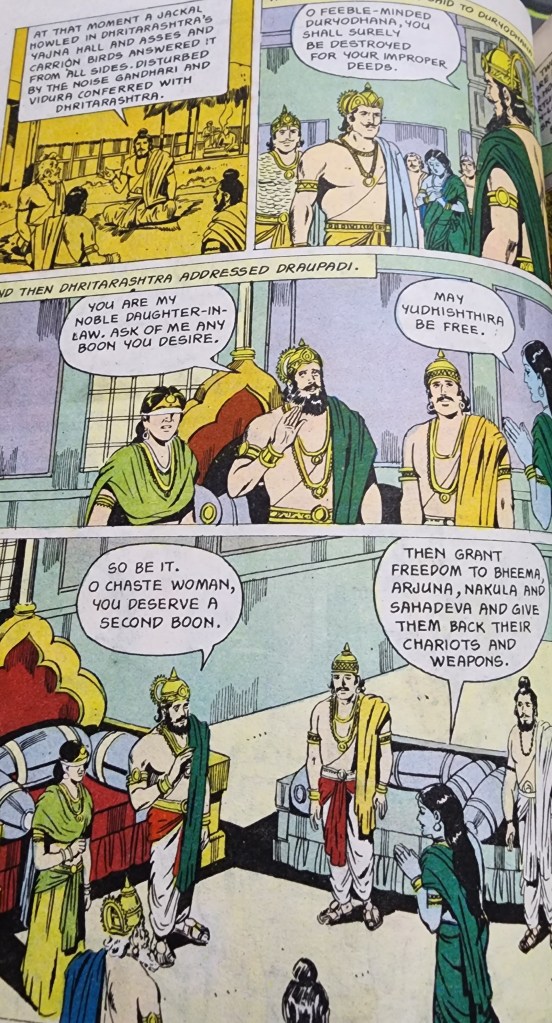

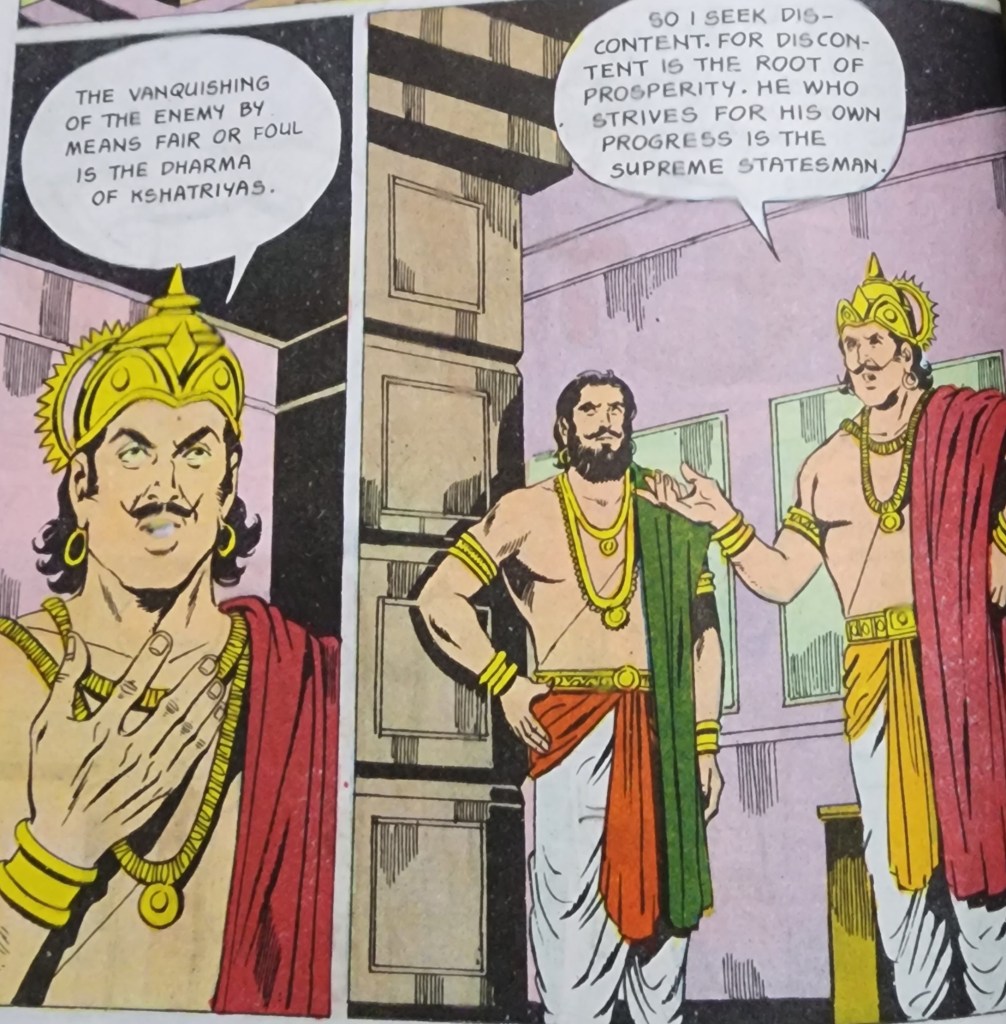

An example of this was seen in my previous article relating to the festival of Deepavali (link to the article in the notes below)*. In that article I had discussed how stealth and deception were the real weapons applied against both Narakāsura and Bali. In the case of Narakāsura the deception was to carry out an unexpected aerial attack against him at night and catching him by surprise. In the case of Bali, the deception was to get him to make a promise that he would not be able to keep and hence be defeated. Both actions were driven by knowledge of the opponents. Bali was honourable and righteous and would never break a promise, guaranteeing his defeat. Narakāsura would never back down from a fight and hence would be slain.

The outcome of the application of deception, however, was completely different in two cases. Bali was defeated without any violence while Narakāsura was killed and many of his troops lost their lives as well. Bali was defeated by the Vāmana avatāra of Vishnu and Narakāsura was killed by the Krishna avatāra. Further, Bali was rewarded by being named the next Indra while Naraka’s name is forever remembered as that of a tyrant. Based on this, the application of deception against Narakāsura is “Katsujiken” or life-taking sword, while it is “Satsujiken” or life-saving sword in the case of Bali. The “ken” or sword in both cases is the concept of deception.

Before the segue into the use of deception against Bali and Narakāsura, I had mentioned how only those involved in a conflict can identify when Katsujiken or Satsujiken is applicable in a given situation. Perhaps even they do not actively think of it in these terms. They “feel” the situation and while going with the flow of the conflict determine the necessary actions. In hindsight the action taken can be classified as either life-taking or life-saving.

So, how do those participating in the conflict identify what the preferred course of action or response is? I opine that the answer is to “listen” to the opponent and therefore the situation. This is not unlike being a good listener in daily life. We all try to be good listeners at work, with friends and with family. The idea is that this will help us identify the actual problem a client is facing and if the people near and dear to us are saying anything that is not explicit in the words being used. In the case of a conflict, specifically a physical one, even if it is a sport, the word “listen” means one should “feel” the fight.

“Feel the fight” or “feel the situation” does not mean just the tactile aspects. It means one should be aware of the opponent(s) and the time and space where the fight is taking place. The word “mindful” can be used instead of “aware” in the previous sentence. One needs “awareness” of a situation, or an individual needs to be “mindful” of a situation. The awareness here includes not only what is happening, but also the intent of the opponent(s) and even the abilities of the same.

In order to be mindful of a situation, during training sessions, it is suggested that one let go of all motivations except to survive. It is suggested that one not try to win, see if a technique works, focus on a given form, try to make the opponent feel bad or anything else. One should focus on Issho Khemi. I discussed this concept in my previous article*. Issho Khmei is to do whatever is necessary to survive.

An example of this, based on my personal understanding, is the is the use of the tachi. The tachi is the curved Japanese sword that was a precursor of the katana. It was worn differently and used very often by cavalry. The tachi also tended to be a bit longer and more curved compared to the later katana, though this is not a hard and fast rule. Also, it was a weapon that came up against Japanese armour (yoroi) often. I was taught by my mentor that since any sword, including the tachi cannot cut through armour, the tachi was not used as a sword.

The yoroi forced the tachi to be used as a hammer or an axe and also as a knife. Additionally, the tachi was used as a lever and a shield as well. The hammer or axe aspect comes as one strikes the opponent with the sword with no guarantee of achieving a cut. This strike allows the sword to be placed somewhere on the armour. Once this positioning is done, one tries to maneuver the tip of the blade into a gap in the armour where a stab can be achieved, fatal or at least debilitating to the opponent. I have been told by some folk with a lot of experience that the initial strike sometimes happened with the back (mune – blunt edge) of the tachi. Also, only the last few inches of this weapon was sharpened to aid in effective stabbing. The rest of it was not necessarily very sharp as it was more for striking and could not cut through armour anyway.

When two opponents in armour and swords go up against one another, they tend to end up grappling. This is because a cut is not possible and a stab in the gaps of the armour is the objective. One of the ways of getting a stab is to get the opponent down and then stab from a dominant position. Also, when the tachi is more a metal rod and less a sword against armour, it is effective as a lever to grapple with and take down an opponent. This is not unlike the way we are taught to use a hanbo in the Bujinkan. Of course, if the sword is a metal rod that can hit, it can also act as a shield to block the same. Thus, the tachi is a staff, axe, hammer and a knife, disguised as a sword.

This same way of using swords is also seen in European martial arts. When armour development improved greatly and full plate harness was used in Europe during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, swords also evolved to the new reality where a cut was useless against armour. Swords became more pointed to enable stabbing. A highly specialized stabbing sword called an “Estoc” was developed which had a square or rhomboid cross section, but a very sharp point. This meant that it was a metal rod with a point, so, no cutting at all, but great thrusting. This also enabled half-swording where one could hold the blade at any position with no risk of being cut.

Of course, even when swords were sharp half-swording is possible. The same is true with a tachi. It just depends on learning how to handle a sharp edge. Based on what I have seen of half-swording, they do seem similar to the ways of using a hanbo as well, just like a tachi. All of this can be simplified and explained by considering how we would use an unsheathed sword. In both European and Japanese martial arts, individuals carried a dagger or a tanto for stabbing once both opponents were down. This was more efficient as it was easier to control on the ground, unlike a longer sword. I am personally not aware of any manuals or specific forms from Indian martial arts where armour was considered and grappling was resorted to, to overcome the same. Please do let me know if anyone knows of the same.

The morphing of a sword into a hammer, knife and shield is an example of being aware of the opponent (wearing armour as a simplistic example in this case) and using a tool, sword in this case, however possible, to achieve survival. So, when the tachi is a shield, it is Satsujiken and when it is a hammer or a dagger, it is Katsujiken.

I started off with this example to show how one must be mindful of the situation in a conflict. But when we consider the development of arms and armour over centuries to counter one another, we realize that the duration of a conflict need not be a short one. It could short for individuals, based on how long they are a part of the same. But the conflict itself might go on for durations which last the lifetimes of multiple generations. In this situation, being aware of opponent(s) is something like the Government of a nation always needing to be aware of the threats to its citizens. Here the intelligence gathering arms of the state are the main enablers of being mindful of the world, beyond just the known enemies of state or opponents of government. This is “listening” or “being aware” in perpetuity.

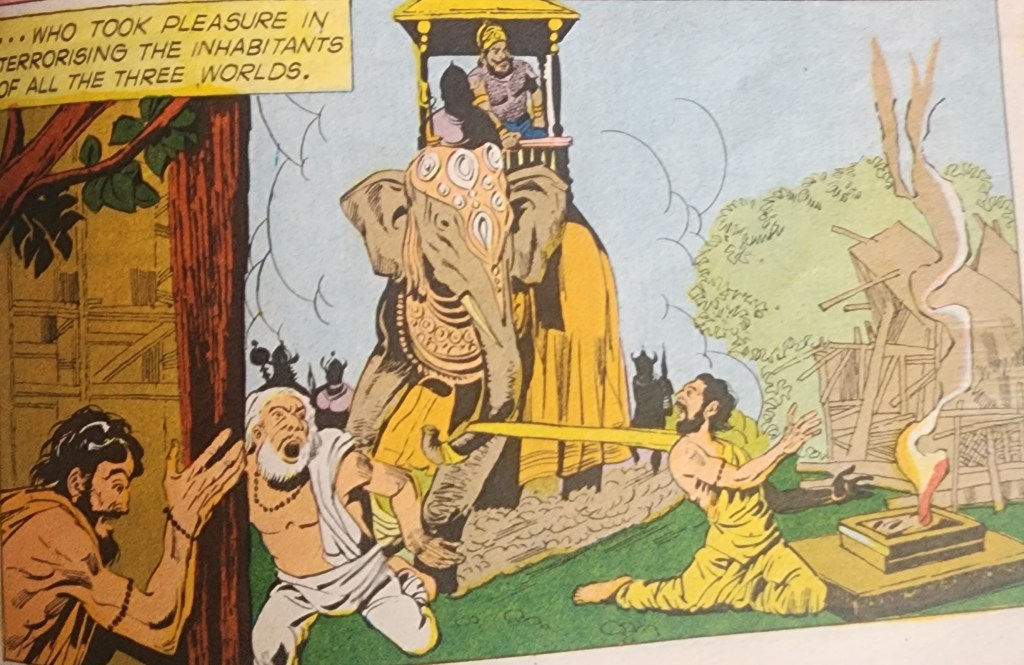

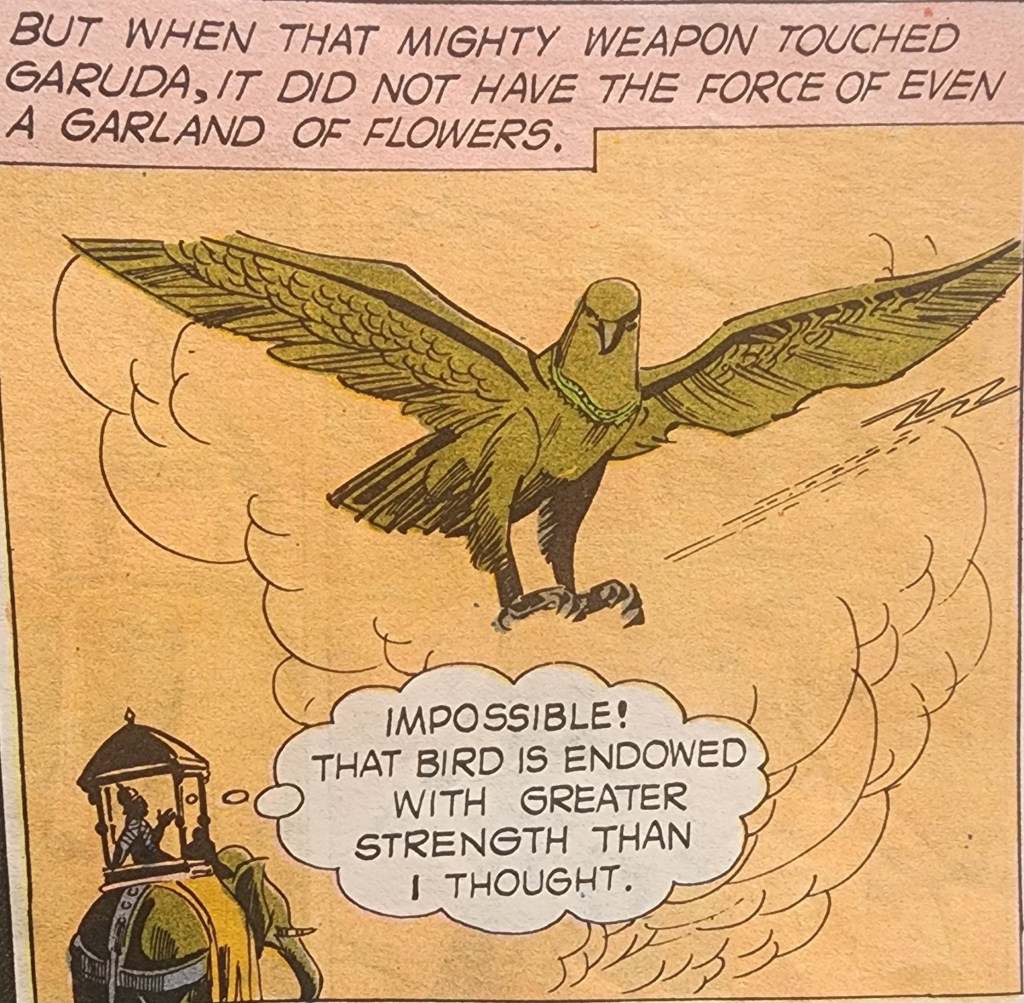

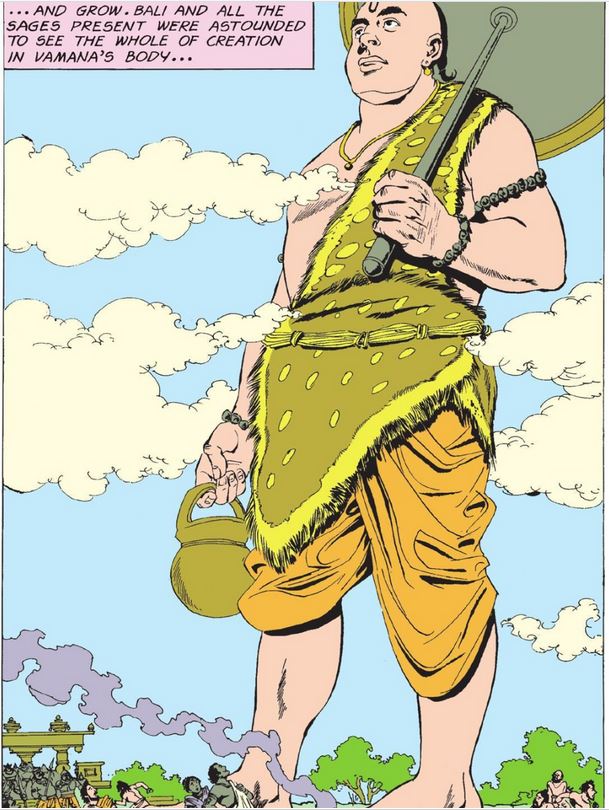

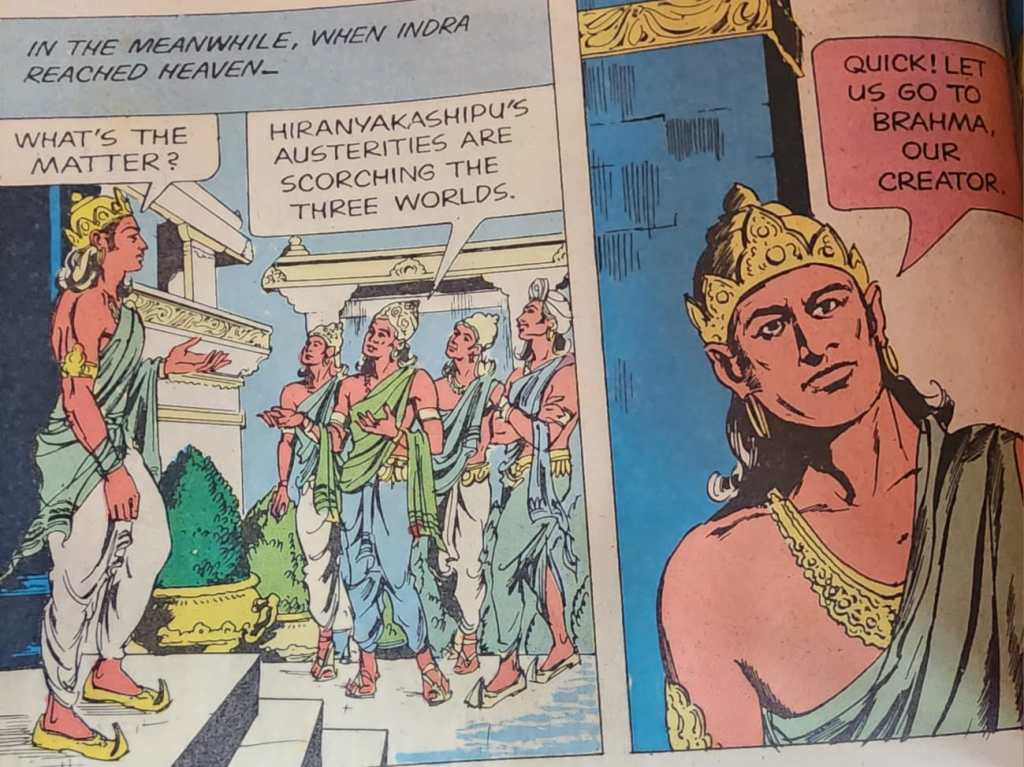

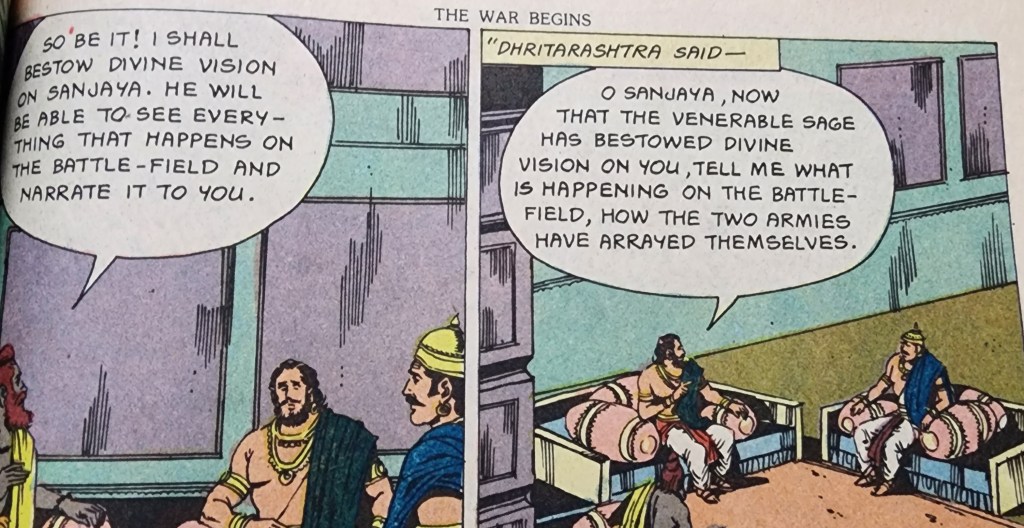

Tales from Hindu culture are replete with the need to be mindful of the opponent(s) abilities. Several avatāras and forms of our Gods and Goddesses were specifically born in that form to counter the ability of a given threat to the world, the threat in most cases being an asura. In my previous article, I have described the purpose of each of the 10 avatāras of Lord Vishnu. The link to this article is seen in the notes below*. I will share specific examples here to elucidate how awareness of the opponent led to the form of God. I am leaving out Narakāsura and Bali as they have already been discussed in great detail above and in an earlier article* (link in the notes).

Lord Narsimha

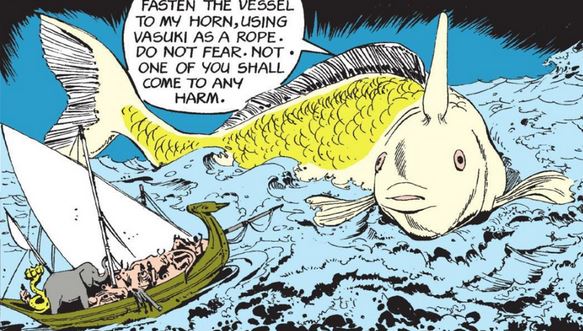

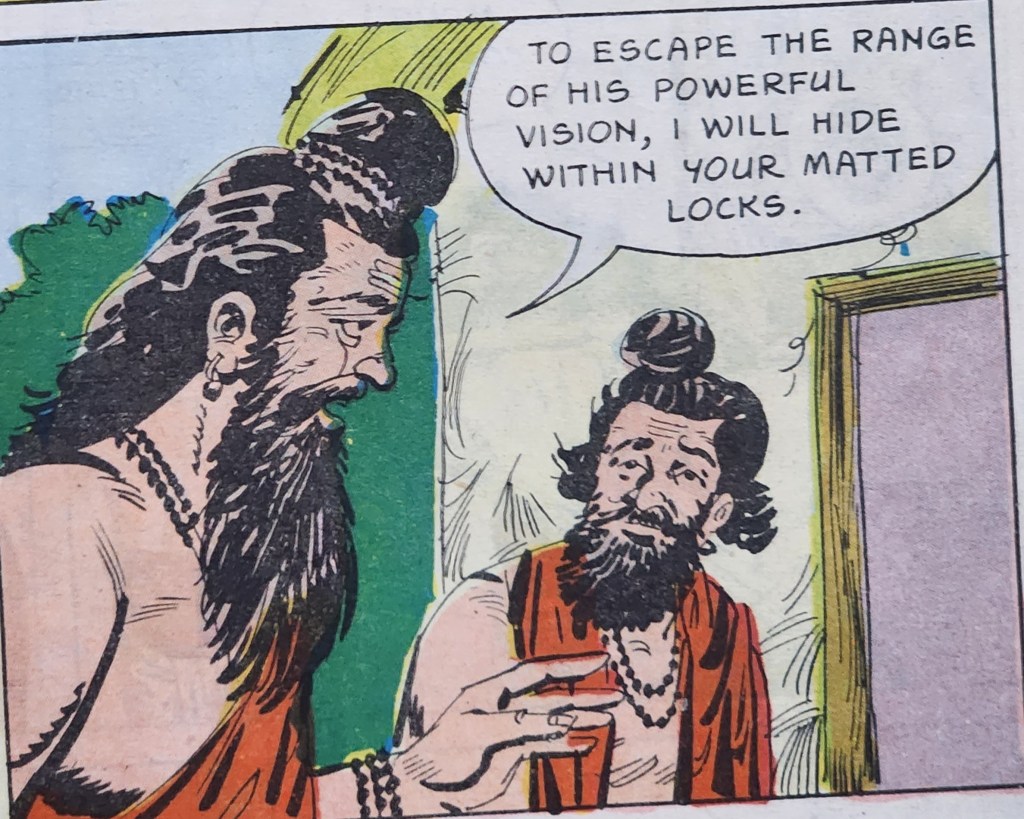

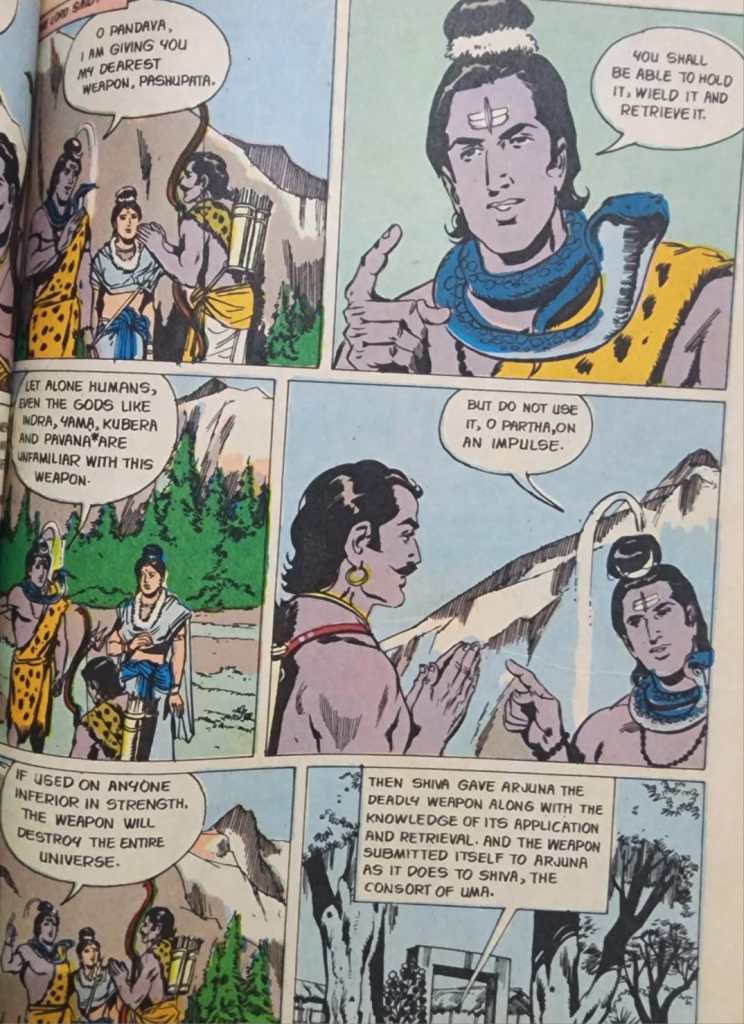

The Asura Hiranyakashipu had a boon (vara) due to which he could not be killed by any man or animal, inside or outside, during the day or during the night. Lord Vishnu took the form of Narasimha to specifically exploit the loopholes in the boon. The boon is the armour/ability in this case and the loophole in the boon is the gap in the armour that can be exploited. Narasimha was neither man not animal, he was both. He killed Hiranyakashipu on the threshold, which is neither inside nor outside, at twilight, which is neither day nor night.

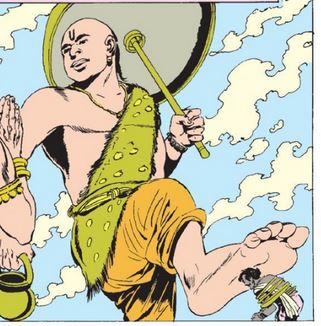

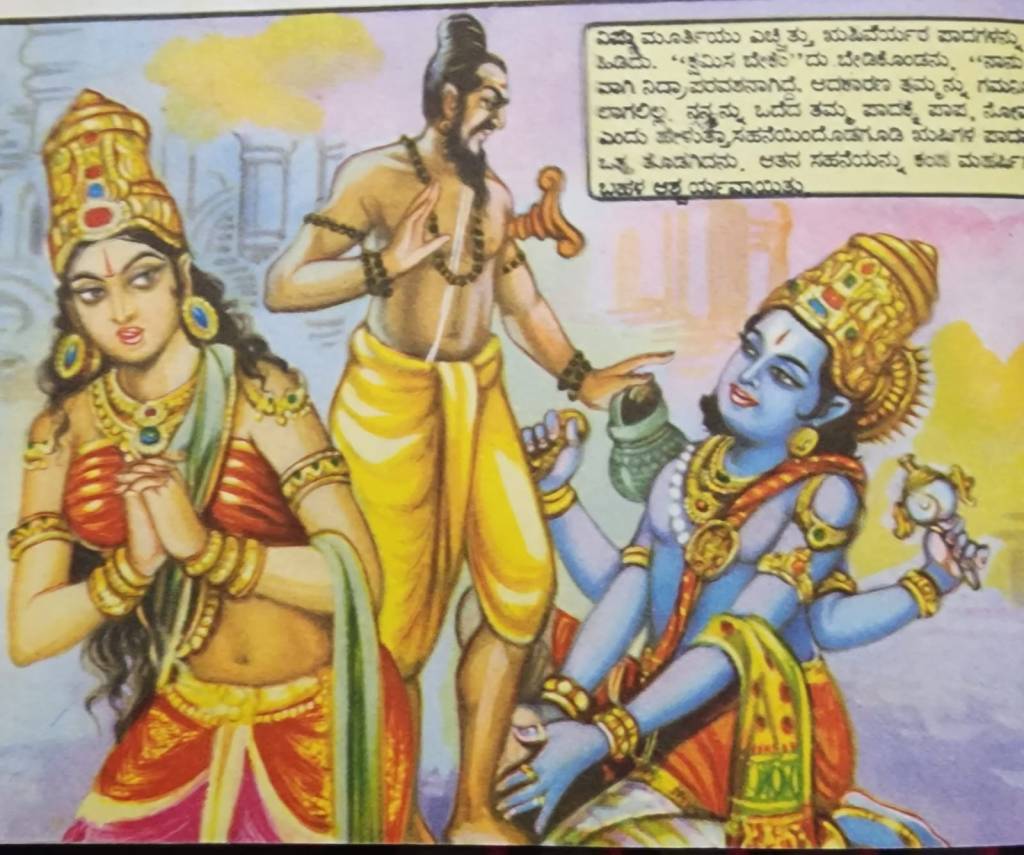

Image credit – “Prahlad”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

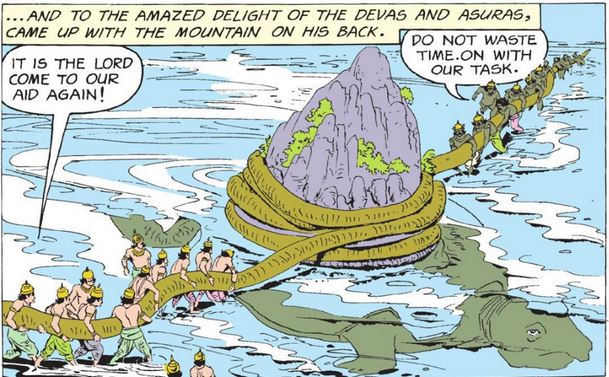

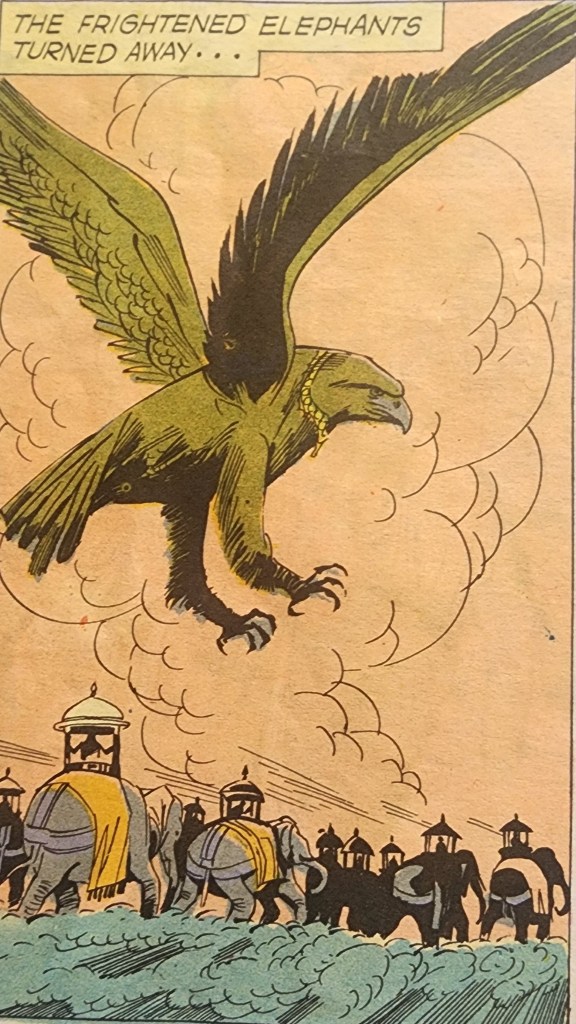

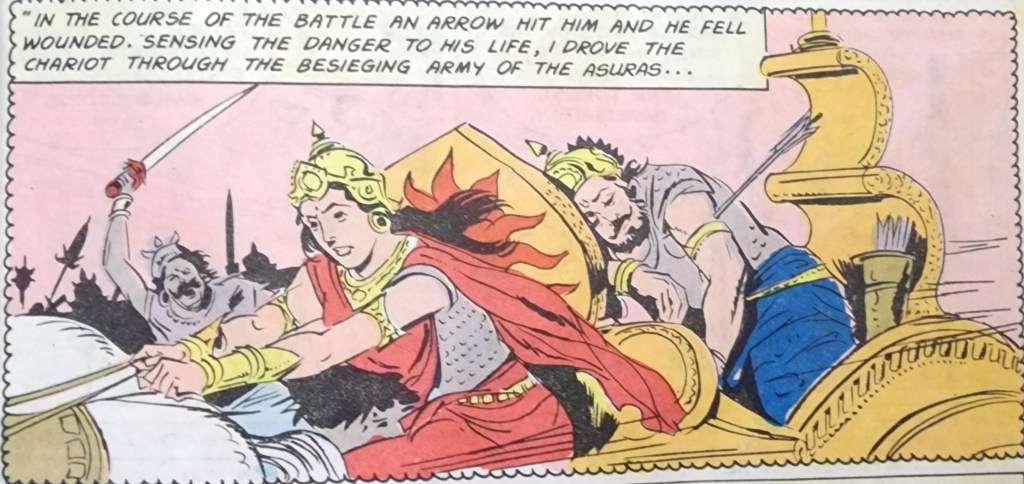

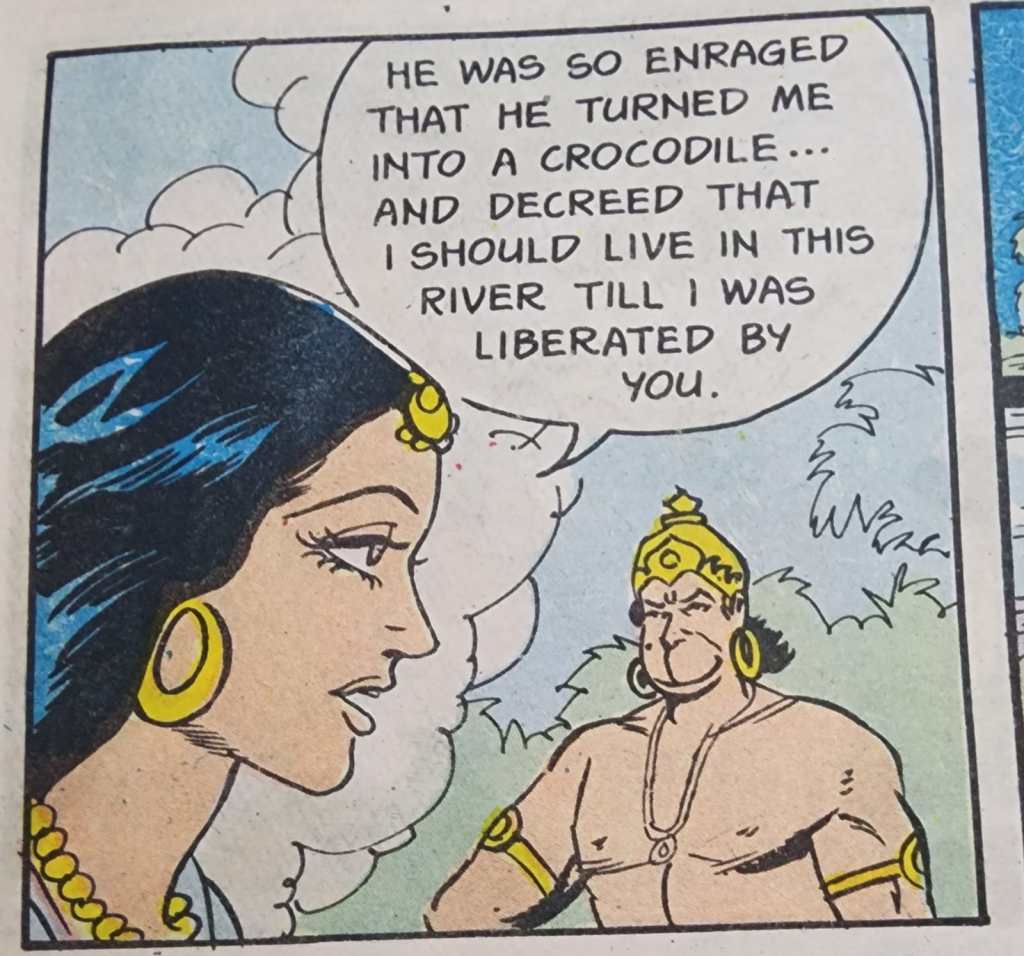

Devi Durga

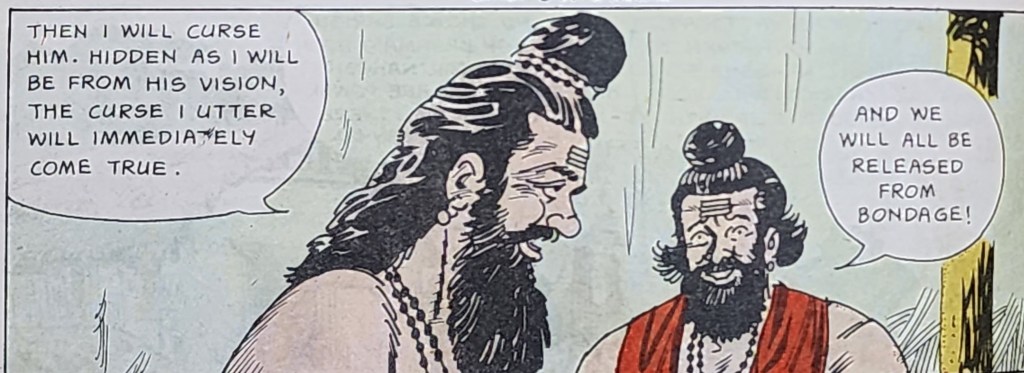

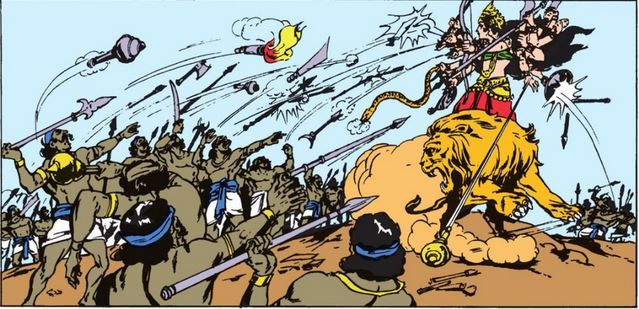

The Asura Mahishāsura had a boon which specifically protected him from all living beings except women. He believed no woman could harm him and hence did not ask for protection from them at the time of requesting the boon. Devi Durga is a form of Devi Parvati or Shakti who came into being to eliminate Mahishāsura. Durga received the weapons of all the Gods which made her the greatest warrior. Mashisha had no protection against Durga as she was a woman and with her martial abilities, she destroyed Mahishāsura.

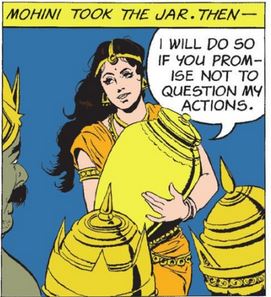

Image credit – “Tales of Durga” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha

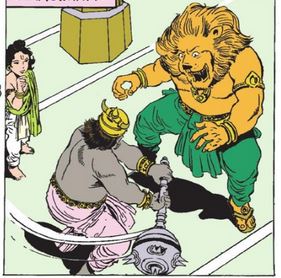

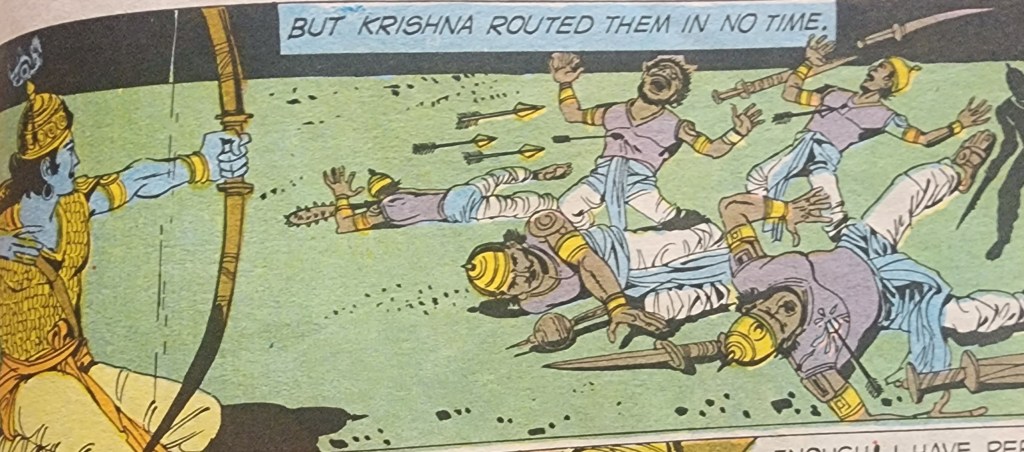

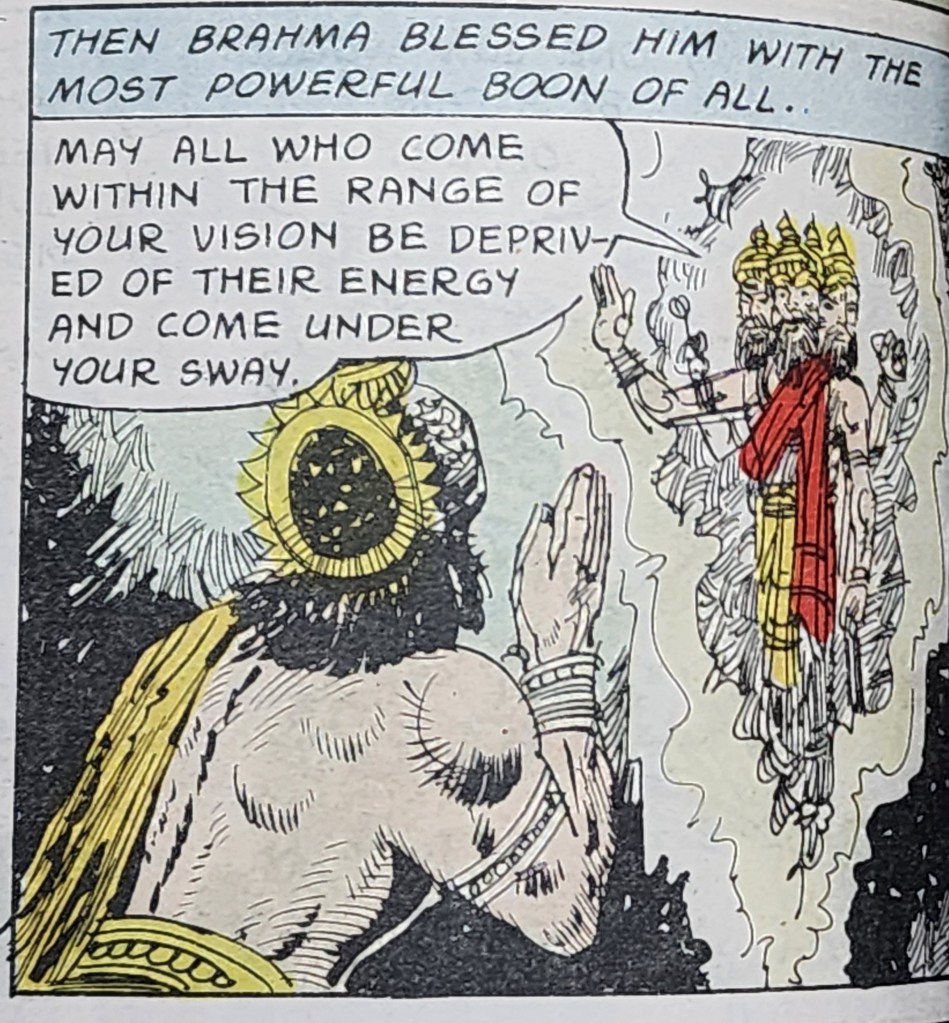

Lord Karttikeya

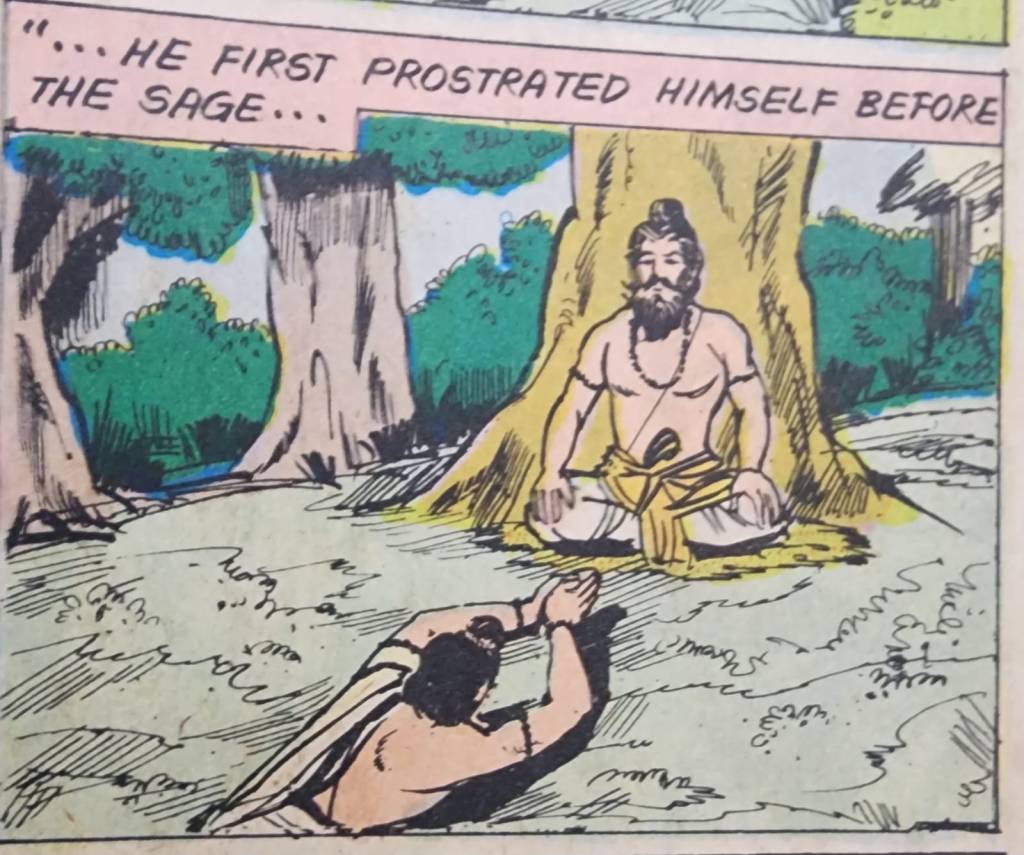

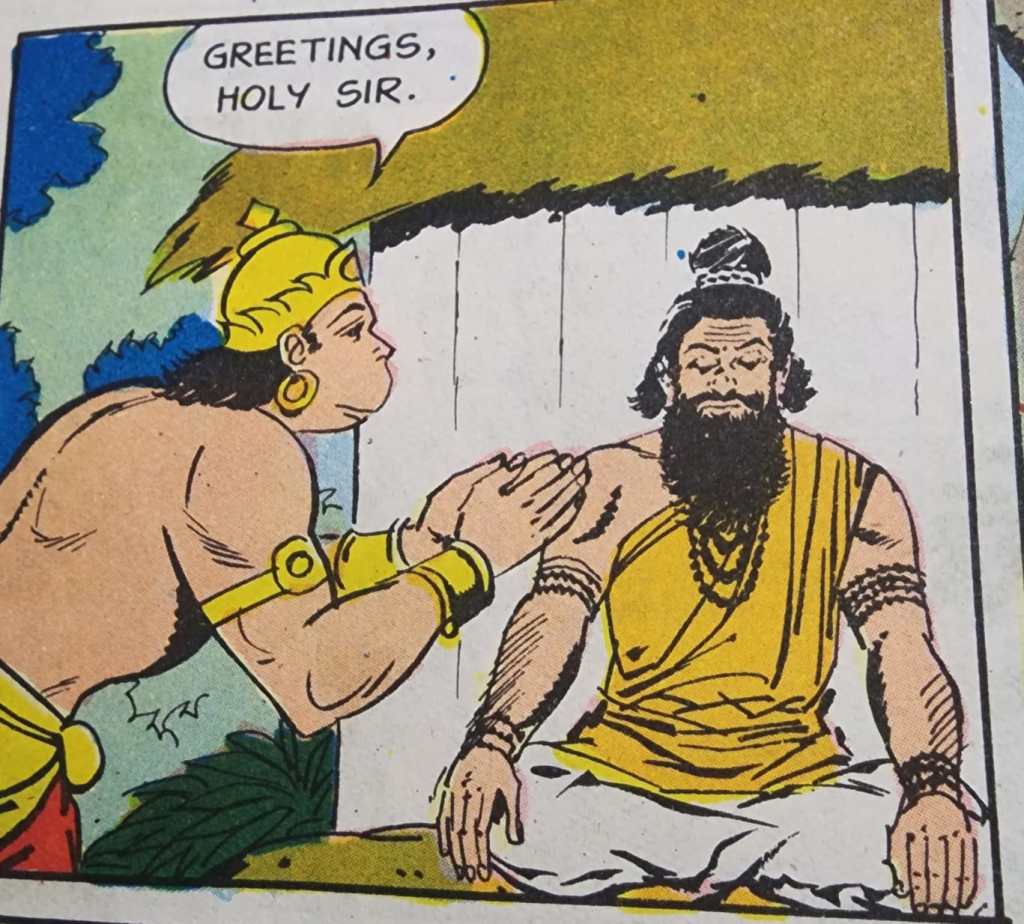

The Asura Tāraka had a boon due to which only a son of Lord Shiva could defeat him. Lord Shiva was in deep meditation and had no wife at the time the boon was granted. Hence, there was no one who could threaten Tāraka. Eventually Devi Parvati married Lord Shiva and Lord Karttikeya was born of them. He eliminated Tārakāsura. I am cutting the story really short here!

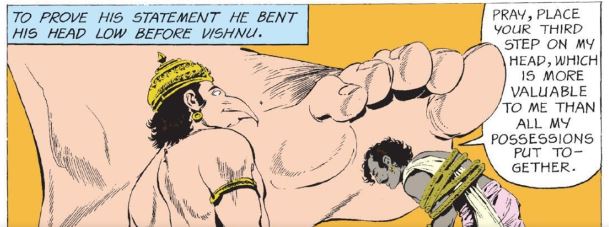

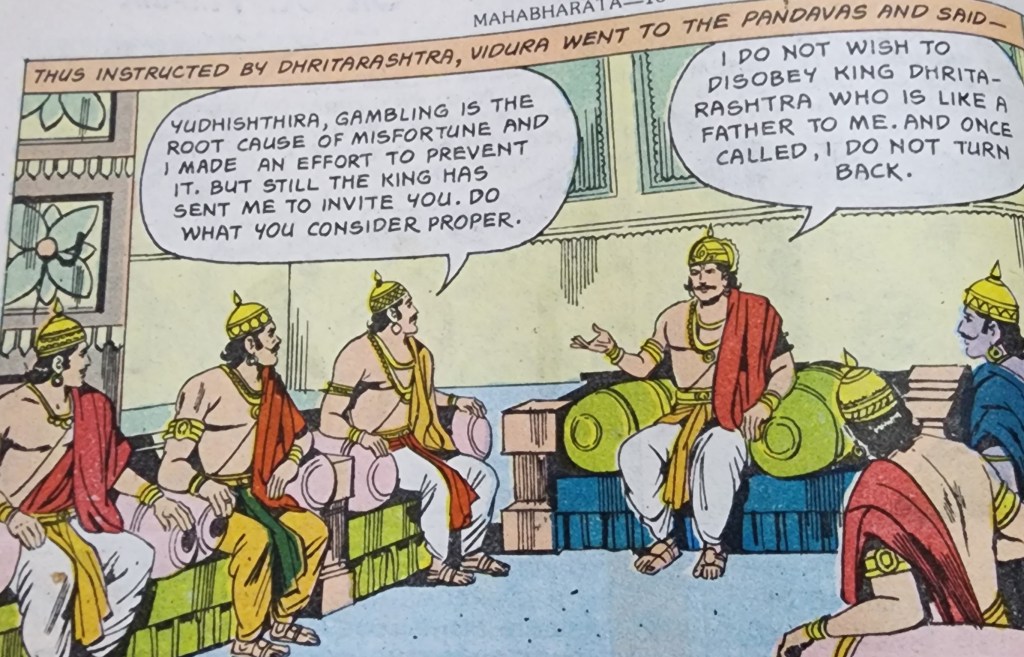

Image credit – “Karttikeya” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha

The above just a very small set of the examples from Hindu culture of being aware of the abilities of the opponent to be able to overcome the threat. I would strongly encourage everyone to read the stories in full. They are a very enriching experience. Hindu tradition is literally chock full of examples that are constant reminders of the need to be mindful of any given situation.

Since we are speaking of identifying a gap or an opening in the armour or ability of an opponent, and the notion in this article is originating from the Bujinkan, which is Japanese in origin, I must share the beautifully poetic words to express this concept. Tsuki, in Japanese, is to punch. Suki is the hole or opening that can be punched. So, many stories from Hindu tradition are all about “Suki to Tsuki”. Identify a Suki or opening to Tsuki, or punch. In other words, find an opening and attack it, exactly like the avatāras did.

Staying with Japanese culture, there are legends of the Muramasa and Masamune blades from medieval Japan. I am not aware of all the stories associated with these swords, but I am sharing a gist of what I know. Blades made by the swordsmith Masamune were supposed to be blades that saved lives. Swords made by the swordsmith Muramasa were supposed to be cursed. They always took lives and brought misfortune to the owners of the same. I have heard some opinions that Muramasa was an apprentice of Masamune’s.

One interesting story about these is about the comparison of which sword was sharper. A sword by both Masamune and Muramasa were left suspended in a stream to check which was a sharper blade. The Masamune blade did not harm any fish swimming past. The fish avoided the sword and never swam into the dangling blade. Vegetation that floated past was cut effortlessly. However, with the Muramasa blade, fish swam into the blade were cleaved effortlessly. But vegetation got tangled on the blade and was not cut. I could be wrong about the details of the story, but I hope the essence that one was a life-saving blade while the other was a life-taking blade is clear. Muramasa is Katsujiken, Masamune is Satsujiken.

There is a manga (Japanese comics) called “Crying Freeman”. In one volume of this manga, the protagonist gets possession of a Muramasa sword and is subject to misfortune++. His wife believes that the Muramasa sword brings misfortune because people try to get rid of it and not learn to use it. She feels that the blade needs its owner to learn to use it in the best manner possible. So, she takes up this responsibility and trains with the Muramasa blade. Send turns out to be right and the string of bad luck ceases. I think this is a wonderful take on learning to be mindful, even of inanimate objects!

Since we are referring to pop culture by discussing manga, I will share one beautiful description of the concept of “do not draw if you are not ready to kill”. In the second novel of the acclaimed science fiction series “The Expanse”, titled “Caliban’s War”, there is face off followed by a shoot-out. Two groups, one of the protagonists who are heavily armed with guns and another of a group of security personnel who are similarly armed are facing off against each other.

Neither wants to start shooting but both are extremely suspicious of the other and on a hair trigger response. One of the protagonists, who has no combat experience, based on his viewing of movies, thinks he can threaten the other group into withdrawal and cocks his gun. This immediately triggers a shoot out and all the security personnel have to be killed. Later one of the protagonists relieves the non-combatant of his weapon and explains that any one with real combat experience assumes that a cocked gun is a prelude to a definite firing of the same and will not wait to see what happens next, they will simply shoot. The person who did it had no idea of this and cost several lives in a tragic and inadvertent situation. I believe the character in the novel who starts the shoot out accidentally is Praxidike Meng.

One last point before we conclude this post. I mentioned earlier in this article that societal norms and a robust legal and justice system can be a deterrent to violence. In other words, there is a systemic incentivizing of Satsujiken over Katsujiken. There is a Sanskrit phase that says “Dharmo Rakshatih Rakshitaha”. It means “Dharma protects those that protect it”. Dharma can be “the right thing to do”. It can also be “that which sustains”&.

If there is a set of rules and practices put in place by a system and this system by efficient and effective performance mitigates violence in society, then that system could be a Dharma. Individuals who follow the system by not violating the rules are upholding the Dharma. In turn, the Dharma or system protects those that follow the rules, or laws. Individuals are protected as those that might consider violence against others are discouraged by the knowledge that they have to bear the brunt of the system if they violate the law (rules). This makes the violators ones that do not protect Dharma. Thus it is a symbiotic relationship; follow the rules to protect the Dharma, and the system, Dharma, protects you because when everyone follows the same, there can be no violation, and hence no violence.

Here, both definitions of Dharma hold good. If one considers Dharma to be “the right thing to do”, following the system/Dharma is the right thing for people to do. Similarly, the right thing for the Dharma/system to do is protect those that practice it. If one considers Dharma as “that which sustains”, the system/Dharma can only be sustained if people practice it. By practicing it, practitioners are letting the Dharma/system sustain them as it protects them from violence and hence get on with lives with less fear.

With that observation, I conclude this series of 3 articles starting with the one about Deepavali. The festival of Deepavali and the Dashāvatāra are indeed a treasure trove of concepts that lead to a plethora of learning from the martial arts.

Notes:

* Deepavali – Light on the Martial Arts

* Dashāvatāra & Budo, Part 1 – Issho Khemi

** Link to the video where the statement is made by Gurukkal, Dr. S Mahesh – watch between the 22nd and 25th minute mark

& I am taking this definition of “Dharma” from the book “Mahabharata Unravelled” by Ami Ganatra. The link to the book is seen below

++ Link to “Crying Freeman Volume 3”