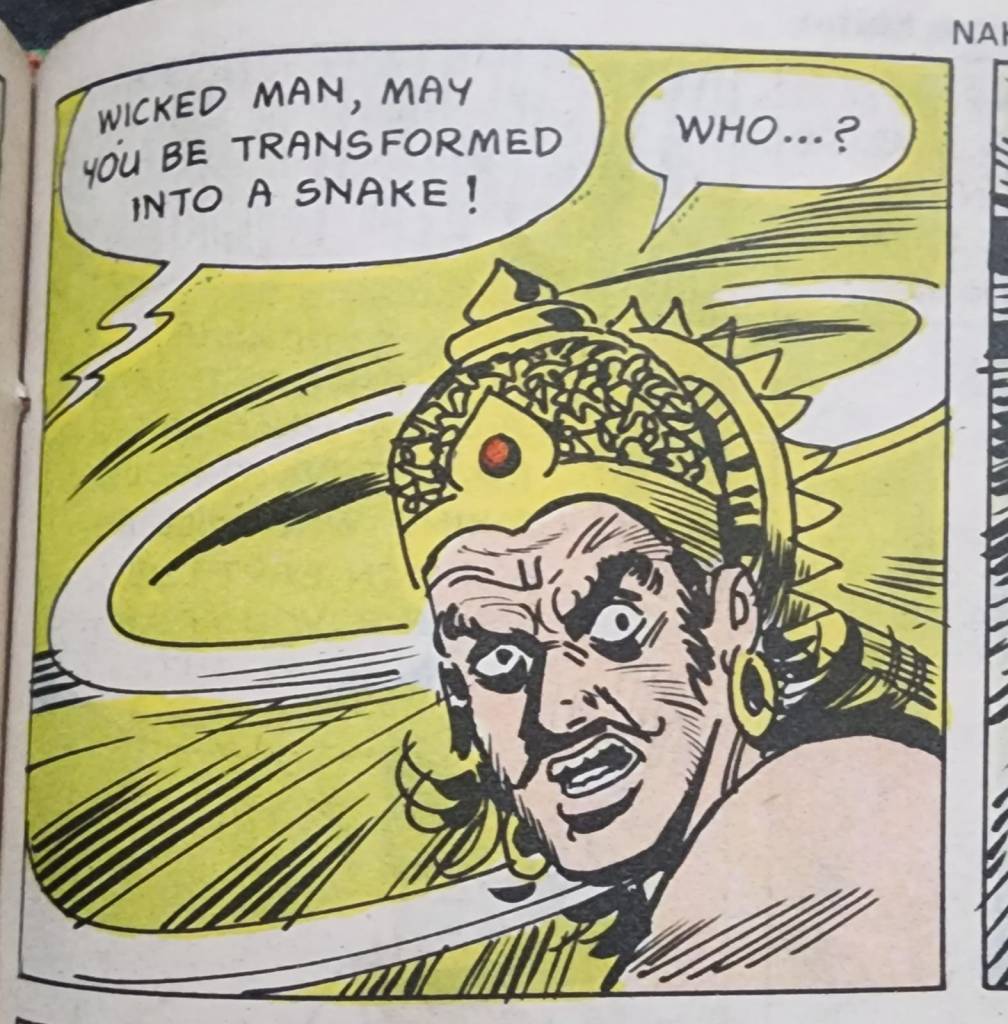

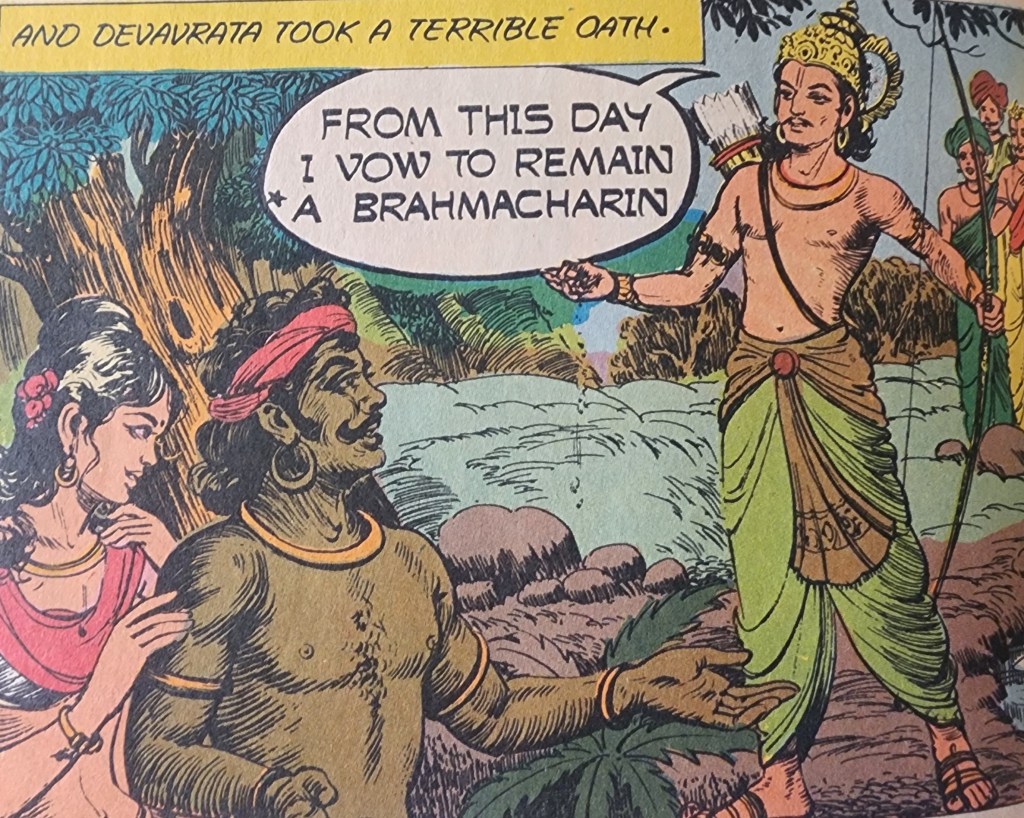

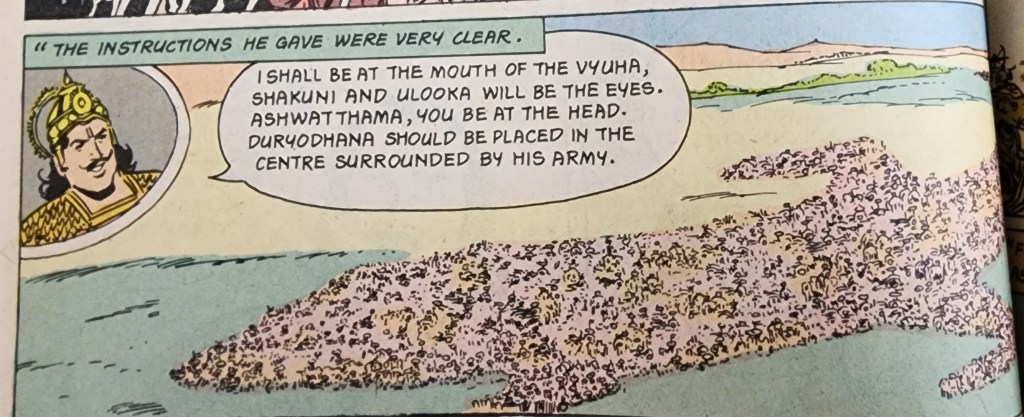

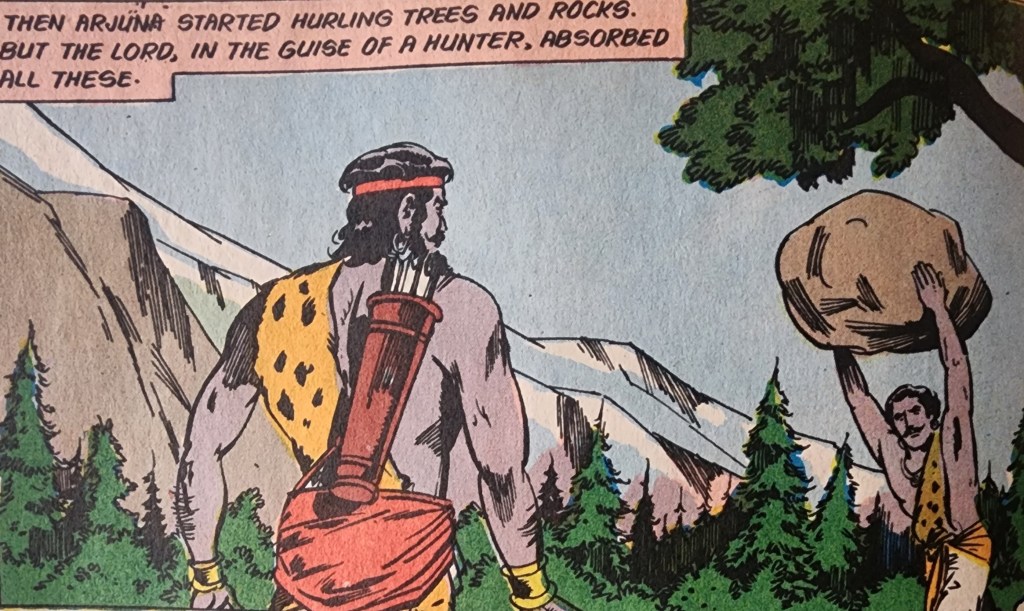

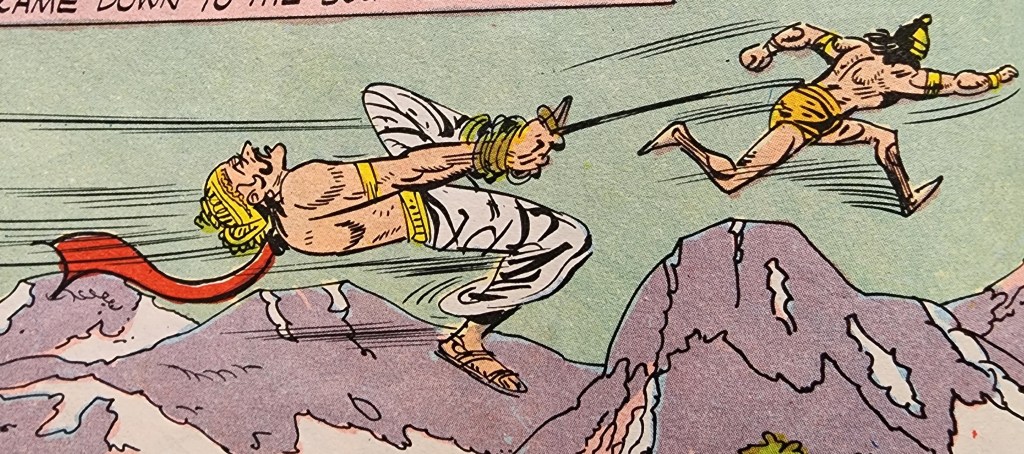

Image 1 – Vaali defeats Raavana

Clarification – In this article I am referring to the great Vaanara king Vaali, who is the brother of Sugreeva. It is the Vaali who is seen in the Ramayana and is killed by Rama. I am not referring to Bali, who can also be called Bali Chakravarthy, who is the grandson of Prahlad. This Bali is the person who interacts with the Vaamana Avataara of Lord Vishnu and is a great Asura king who is celebrated in the festivals of Bali Paadyami and Onam. I am explaining this since I have seen some people refer to Vaali, the brother of Sugreeva as Bali and in some television serials as Mahabali Bali. This is just a different pronunciation of Vaali, which is pronounced as Baali but written as Bali. Of course, Vaali is also written as Vali sometimes. It is assumed that the person reading the name knows that “Va” has to be pronounced as “Vaa” or “Ba” as “Baa”. But some people might not realize this and hence this clarification. Just another point here, Bali Chakravarthy is Bali, but Mahabali Bali is actually Mahabali Baali.

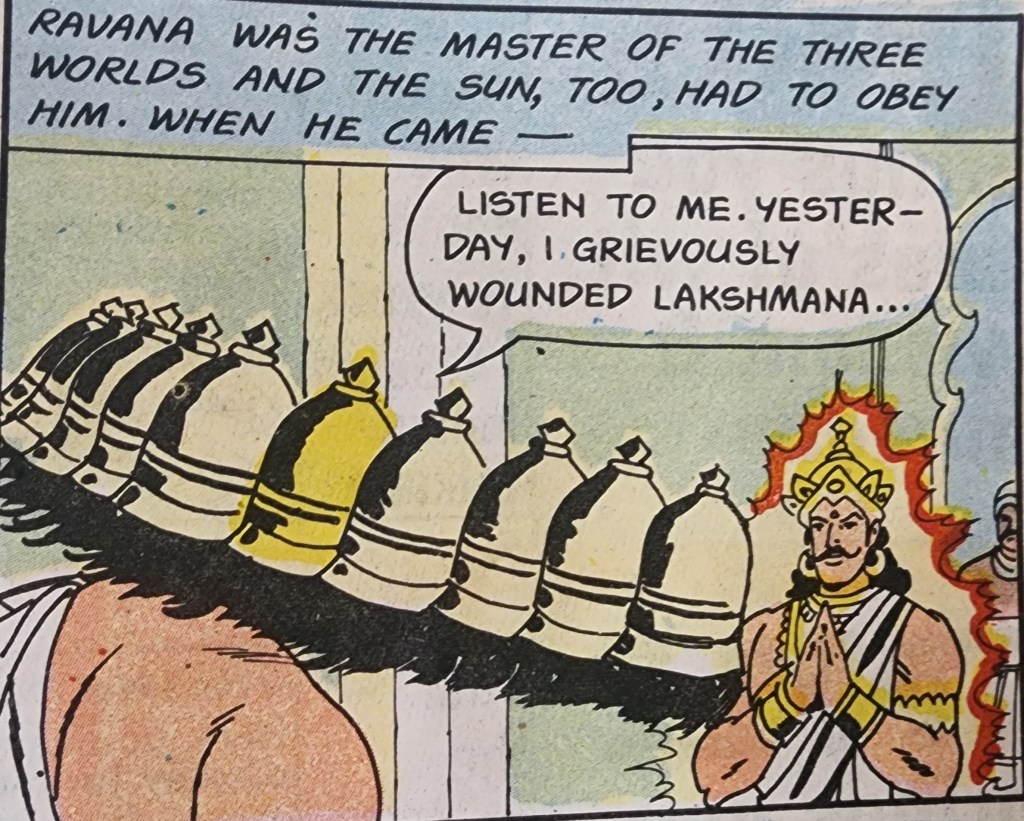

Vaanara king Vaali, elder brother of Sugreeva was an incredible warrior and martial artist. The very best! He had defeated in single combat three extraordinary opponents which give testament to this fact. The first and foremost of these was Ravana, who was as great a warrior as one could think of. Vaali defeated him in a manner so nonchalant and effortless that it boggles the mind.

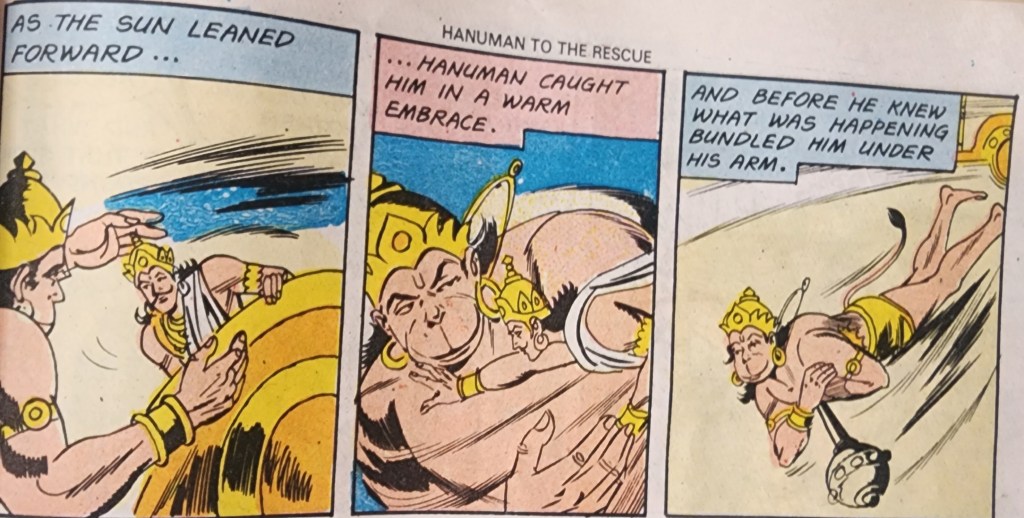

We need to remember that Vaali was a Vaanara and therefore had a tail. Like at least some Vaanaras, he had a prehensile tail, which he could move as he preferred and use as a weapon by itself. Raavana apparently attacked Vaali with stealth, from behind, when the latter was busy in performing the Sandhavandana*. Raavana grabbed Vaali’s tail as the initiation of the attack. Vaali used his tail to fend off and defeat Raavana, while never deviating from the performance of the Sandhyavandana. Raavana was left bound and helpless by the time Vaali had finished the Sandhyavandana. Sandhyavandana is still performed by many to this day and even when performed to its fullest extent, does not take very long. Also, it is mentioned that Vaali did not realize what he had done with his tail until Raavana begged for help when Vaali had completed the Sandhyavandana. Thus, Vaali not only defeated Raavana effortlessly, he did it in a manner most humiliating and in short order. Raavana, thus defeated, sought his friendship and gained the same.

Vaali also fought and defeated a shapeshifting Asura called Dundubhi. Dundubhi was an incredible warrior and challenged all known great warriors to prove his own superiority. Dundubhi was a brother-in-law of Raavana. Dundubhi challenged Vaali to a duel when he heard of the prowess of the latter. In the great fight that ensued, when he realized that Vaali was more than a match for him, he turned himself into a massive buffalo to continue the fight. Any experienced martial artist will generally agree that martial skills are designed to fight against fellow humans, and the same skills will not work against other animals with different body types. A normal buffalo is much larger than a human and fighting one is a daunting thought. So, fighting a buffalo many times larger than a normal one would be exponentially harder. Of course, Vaali was a Vaanara and had a tail, so his skills would be different, but the task would be difficult nevertheless. Vaali of course, prevailed. If the Ramayana TV series from the 80s is to be believed, Vaali fought the gigantic buffalo unarmed, which makes the feat even more astonishing. He even hurled the massive buffalo carcass quite some distance with just his strength. The skeleton of the giant buffalo is later used as a test of Rama by Sugreeva.

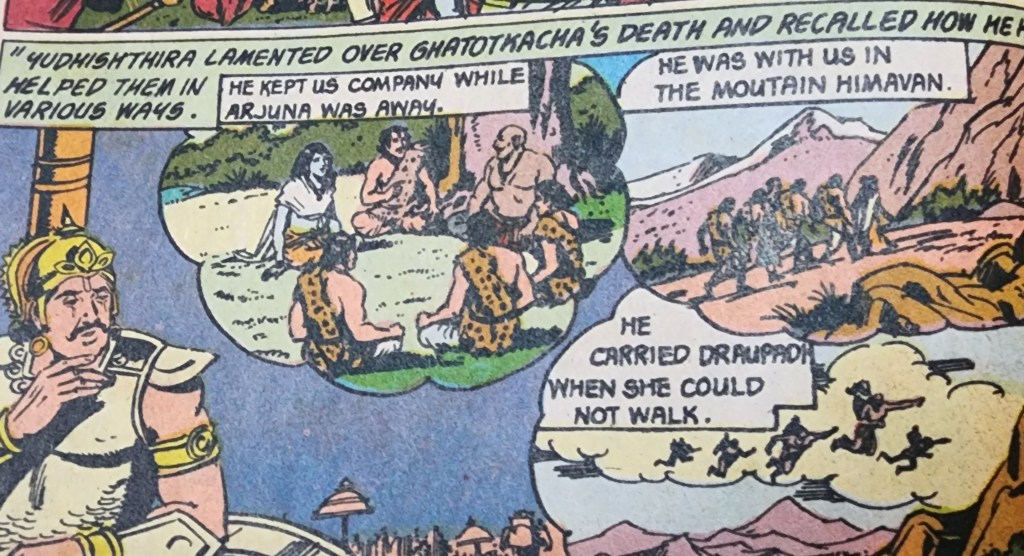

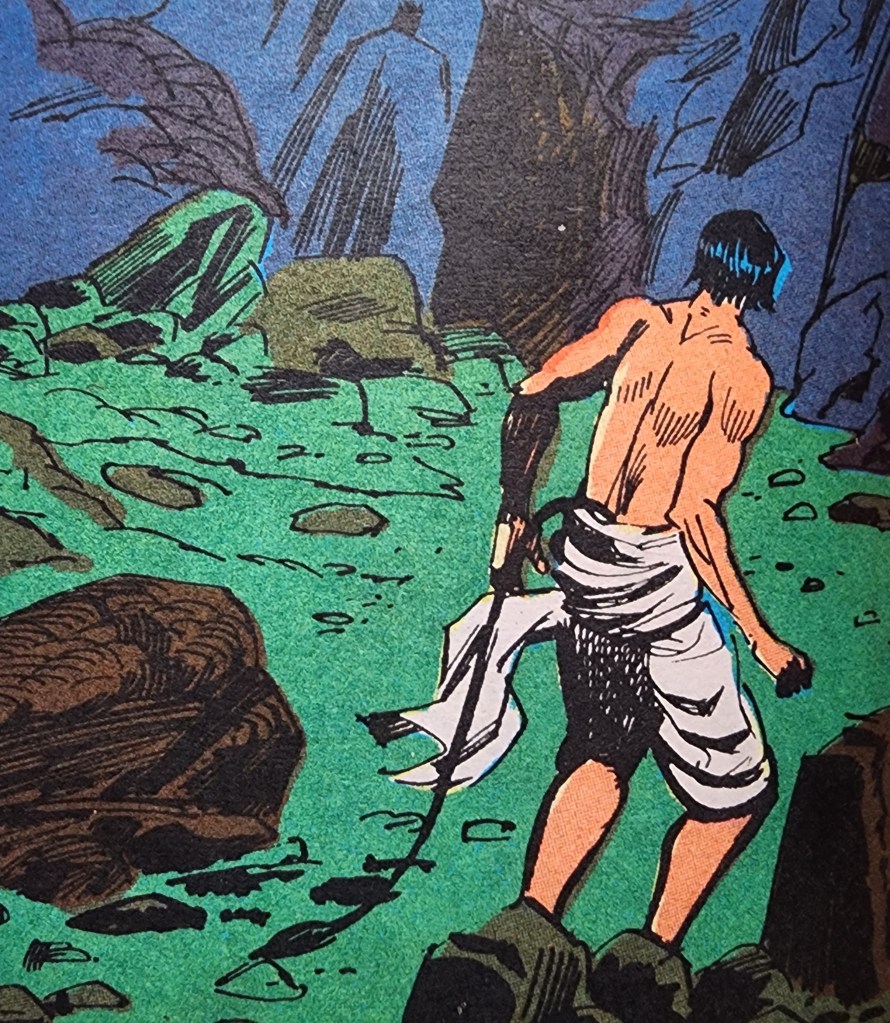

The third famous duel of Vaali’s is with Maayaavi, another extraordinarily powerful Asura who challenged him to a fight. Maayaavi was a brother of Dundubhi’s. The fight between Vaali and Maayaavi eventually moved to cave where Sugreeva stood guard at the entrance. The fight between the two lasted a year before Vaali prevailed. There are other aspects of this story that are not relevant for this discussion and hence I am leaving those out.

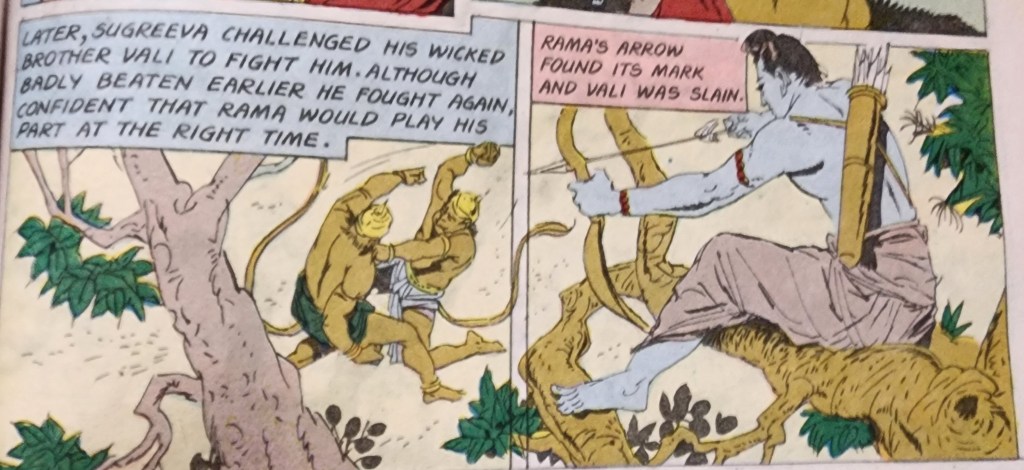

Image 2 – Sugreeva guarding the cave where Vaali and Maayaavi are fighting

One of the reasons Vaali was impossible to defeat in combat was a boon that he had. He had a boon from Indra which resulted in his gaining half the strength of anyone he is fighting. Sometimes it is said that he had a pendant gifted to him by Indra, the wearing of which resulted in same. So, the boon was the pendant. Either way, Vaali’s strength would increase while that of the opponent would decrease by half. So, apart from being a phenomenal warrior, Vaali also ensured that the opponent was diminished just by dint of being his opponent. The boon and his own skills pretty much made him invincible.

Now, there are a few points to consider here. Does, “half of the opponent’s strength” mean just physical strength or does it mean half of the skills? I do not know. Also, what constitutes a fight and what makes one an opponent? Does one have to be actually fighting Vaali for the boon to take effect? Or does just having ill intent towards Vaali result in the boon diminishing one’s strength/abilities?

If just having ill intent towards Vaali results in the opponent being diminished, then were Rama’s abilities as an archer diminished when he decided to shoot at Vaali from hiding? Is that why he could not distinguish between Vaali & Sugreeva in their first duel? Is that why Sugreeva needed to wear a distinguishing garland to identify himself during the second duel? And was Rama’s eyesight diminished due to the boon or was it just the distance and resemblance of the brothers? If all this was happening, were the two tests set by Sugreeva that Rama passed, sufficient in the first place? Or were the two tests specifically designed by Sugreeva, who knew of Vaali’s boon, to check if Rama operating at fifty percent would be able to strike the target (Vaali). I do not have the answers to any of these questions.

Next, when we consider the duel with Raavana, was Raavana an opponent just by having ill will towards Vaali? After all, he initiated the attack and with stealth, from behind. Vaali defeated him without even realizing he was in a fight! How cool is that! Based on this encounter, it does seem that Vaali does not need to be in an active fight for the boon to take effect. Any person, who puts to action a thought to cause harm to Vaali seems to be deemed to be an opponent and the boon diminishes that person while enhancing Vaali.

An aside here, this encounter gives a great opportunity to discuss Vaali’s Sakkijutsu (intuitive abilities) and perhaps as a consequence of that, his Nanigunaku Sanigunaku (natural nonchalance). Was Vaali’s enhancement by half of Raavan’s stealth (a skill by itself) his intuitive ability to sense an attack? And hence was his enhancement the ability to start a fight without his opponent realizing that it had already started (a stealth attack met with a stealthy defensive offence)? After all, if he could not know a fight was occurring, how could any opponent sense the same (Sakkijutsu of the opponent nullified)?!

Now, let us consider the fight with Maayaavi. Maayaavi supposedly ran to hide in a cave when he knew he was outmatched. But Vaali pursued him to finish him off. In this situation, if the opponent has decided to escape and thus end the fight, he is no longer an opponent right? If yes, does his diminished skill and strength return to its full potential? And does that mean Vaali’s ability to tap into this resource from the opponent also cease? Or is that added to Vaali’s own skill set for good? If yes, is Vaali potentially going to improve forever, with every fight? And can his opponents of the past, if they survive, ever go back to their full strength? And if they do, does the siphoning off due to the boon not be in effect anymore? The answer to the last question seems to be that it does not, for Raavana, was still as great and dangerous a warrior as ever.

Also, the fight between Maayaavi and Vaali lasted a year in the cave. This does seem strange, considering Maayaavi was running for his life (not a strategic retreat) according to the story. Vaali had defeated the other opponents in far shorter times. So, did it take Vaali a year to defeat an opponent who was already defeated, a year, because that Asura was not really an opponent anymore? And since he was hiding and trying to avoid a fight, was his ability not diminished anymore and therefore Vaali not enhanced any further? I would say that it definitely seems so. For trying to find a person in hiding and who is only going to fight to survive, mostly to get away is far harder than one on the attack, simply because the opponent’s movement no longer offer openings to exploit. Add to this the fact that Vaali is no longer enhanced and the opponent diminished, it would take a lot longer. So, no wonder this fight took so much longer, for Vaali as not hunting, not fighting.

In conclusion of the discussion about Vaali’s boon, it does seem that the intent of the other person towards Vaali is what triggers it. If one has malicious intent towards Vaali, the boon takes effect, if one does not, the boon not get triggered either.

Another aside here. If having no ill intent towards Vaali was the key to nullifying his boon, was Ahimsa the answer? Not the “non-violence” Ahimsa, but Ahimsa from a martial perspective. Here Ahimsa is not about not doing violence, it is about not looking to do violence. A link to my article about Ahimsa from a martial perspective is seen below**. Rama was looking to punish Vaali for stealing his brother’s wife, not trying to pick a fight with him or to hurt him otherwise. So, if he was trying to punish Vaali, does it mean he was trying to right a wrong? Was this why he was able to succeed despite the boon? Or did the boon not take effect as Rama’s intent was not to hurt Vaali but to protect Sugreeva? Or is all this just semantics on my part? Perhaps it will be explored at some future time.

In the Bujinkan, we learn three concepts that go hand in hand. These are, “Toatejutsu”, “Shinenjutsu” and “Fudo Kana Shibari”. These are detailed below.

Toatejutsu means striking from a distance. It does not necessarily mean something like shooting with a gun, but it could. It refers to the fact that one could affect the opponent before being in the striking range of the weapon on hand, irrespective of what that is.

Shinenjutsu means capturing or maybe affecting the opponents’ spirit, or the will to fight. This is not about magic, it is about being in a position or situation where an attack would leave an opponent vulnerable, making the attack not worth the attempt.

Fudo Kana Shibari means to hold the opponent in an immovable (unshakable) iron grip. This again is not necessarily about physical immobility though it could be that. It refers to leaving an opponent unable to decide what to do and how to move.

When taken together, the three concepts would mean something like “Strike from a distance at your opponent and capture her or his spirit in an unshakable iron grip”. In more mundane terms, it could mean “Leave your opponent incapable of deciding what to do by affecting her or his will to fight even before starting the fight from the expected physical distance”.

If the above situation can be created vis-à-vis the opponent, the result is that the opponent is left wondering when to attack and how to attack, and even more importantly, if there is an option to attack at all. The risk an opponent opens herself or himself to due to an attack seems great and causes hesitation in the opponent. Once this happens, the opponent can no longer have any momentum or flow in the attack and cannot press home any advantage with an initial attack. This leaves the opponent thinking about the fight as much as he or she can actually fight. Thus, the fighting ability is effectively limited and this is what can be said to be the diminishing of an opponent. Whether the diminishing is by half the ability, is up to interpretation. If we can say that the opponent has to think twice about every move, instead of moving with no need to think too much, we could say the diminishing of the opponent is by half as thinking twice means half the number of attacks. 🙂 But I indulge in semantics here, everyone can make up their own mind about this.

The words above might seem like a great solution in a fight, but are these concepts practical in a real fight, where there are no rules and the end result might be death? I will explore this with a look at a few more concepts described below.

There is a concept called “Kurai Dori” that is taught in the Bujinkan system of martial arts. It translates roughly to “strategic positioning”. It means, in response to any attack, find a position in space that, when taken, minimizes risk to oneself and makes any further attack difficult, if not impossible. In other words, when attacked, find a place where you are safe and attacking is either difficult or risky for the opponent. This is not to say that it is a finishing move. This concept is dynamic and one has to apply it continuously in any conflict situation to stay alive and over time mitigate the attack sufficiently. The individual techniques applied can be anything, but after kurai dori is achieved. Conversely, the techniques applied can be to achieve kurai dori as well.

Next, there something we are taught called “Cut Space”. It is about cutting empty space around the opponent, which is meant to discourage the opponent from making an attack. It might also force an opponent to move away from the current position, ceding more space for one to maneuver in. This concept is also applied to distract the opponent, by cutting in a space which was not an intended attack, but once the opponent’s attention is taken to the space where the cut/attack occurred, another opening might open up, which can be exploited to the detriment of the opponent. A variant of this concept can be “Put something in space” in order to deter the opponent from an attack. An example of this from the last few hundred years would be use of land and sea mines. These cause the opponents to rethink attack routes and gains times for the defender, and allows troops to be used elsewhere.

The third important concept relevant to this discussion comes from a statement that I once heard from Nagato Sensei, one of the most senior most practitioners and teachers of the Bujinkan system. He said, the concept of “Sakkijutsu” is the beginning of the Bujinkan system of martial arts. Of course, Sakkijutsu is something a student learns and comes to express after many years of training. But it is said that, only once a student can realize that she or he can express Sakkijutsu is that person a true student of the Bujinkan, and ready to explore greater details of this system of movement/fighting. Sakkijustsu refers to the ability to intuitively realize the threat that is present and how it might be manifest. Of course, this is not magic, it is a combination of lots of training hours, life experience and mindfulness/awareness of the surroundings.

Lastly, Bujinkan practitioners, are made aware over time, that in a real conflict situation, survival is vastly more important than victory. This realized, every movement is geared towards kurai dori explained earlier, but in survival mode. One only takes an opening against an opponent if he or she is fully protected. Self-protection is key. The learning of this concept is to not have any motivation towards victory, but to use kurai dori to stay protected at all times, until a safe opening to exploit, presents itself. The opening once exploited against the opponent might lead to victory, but more likely to the mitigation of the attack by the opponent.

To put the above four concepts together, consider mastering the following situation. One intuitively realizes the attack originating from the opponent (sakkijutsu) and cuts the space where it would happen. The opponent, being denied that space for the attack has to reconsider her or his moves. This moment of hesitation allows the defender to move to a safer position, applying the principle of kurai dori. This rigmarole, as experienced from the opponent, if it continues, might eventually lead to the opponent withdrawing or leaving an opening in a desperate attack (of course the defender might give out as well). The withdrawal or desperation is a consequence of having to rethink moves constantly, never being able to achieve any flow or momentum in the attack. This constant reconsideration is fatiguing to both mind and body, and leads to the diminishing of the opponent, as described earlier. On the other side, the defender, is moving at every instant towards a satisfactory outcome due to the diminishing of the opponent, and this is an enhancement of the same.

In simpler terms, all the above concepts together make the opponent uncertain of the attack and their own ability to pull it off. This creation of doubt diminishes the opponent. When one does not commit to an attack and remains nonchalant about the conflict, triggering a response to a fake movement has a greater probability of creating an opening to subdue the opponent. It also can, with sufficient maneuvering make them attack in a way that creates an opening that can be exploited. This ability to create openings in the opponent enhances one’s ability to survive and end a fight. If done correctly and for long enough, the opponent might just retreat and end the fight. This then is how to diminish an opponent while enhancing oneself (if only to survive and not necessarily to win). It cannot be said if the opponent is diminished by 50% and the other side is enhanced by the same 50%, but the idea of diminishing the other while enhancing oneself holds true.

So, a practitioner of the martial arts, with many years of experience, has access to concepts and practices which allow a replication of abilities that could mirror the boon that made Vaali impossible to defeat. I hope with the above few paragraphs I have shown the same. Considering that the Bujinkan system is a real & extant martial art, the Bujinkan system, practiced by several thousand students on a daily basis, all over the world, I hope at least a few might agree. 🙂

A few final thoughts about this exposition. If Vaali had the ability to make opponents uncertain and think a lot, and was so proficient at this that his ability came to be deemed a boon, Vaali is even more awesome than originally observed! Does the creation of the idea of a boon mean he was the only one at his time who had this ability? Or was it he who was most proficient and his expression of this seemed to be above and beyond what anyone else from that era could manage? I have no answers, just the questions.

Additionally, if the possession of the boon was indeed a story, was it cleverly used as disinformation to put people off from picking a fight with Vaali? After all, the boon was supposed to be from Indra himself. Was Vaali’s skill so out of this world that it had to originate with not just a Deva but with the King of the Devas? Vaali is also mentioned as the son of Indra (divine or spiritual son, not biological), so it all works together brilliantly in reputation development and hence in conflict management (creating an aura of invincibility to deter opponents).

Lastly, sometimes the boon is mentioned to be in effect only when Vaali wore a pendant granted by Indra. Was this a clever disinformation tactic as well? If an opponent believes in the boon and still chooses a fight, if Vaali turns up without the pendant, does that make the opponent overconfident and therefore let down her or his guard? Is the pendant theory a clever bait? Again, this is a question I have no answer to.

However one looks at the Boon possessed by Vaali, it is a wonderful opportunity to observe a large number of martial concepts/practices and how the same could have always been attempted and applied by humans over millennia.

Notes:

*A ritual performed thrice a day (but mostly once and in most cases, not at all these days) as a salutation to the Sun. It has other aspects included and need not ONLY be a salutation to the sun.

**https://mundanebudo.com/2022/10/13/ahimsa-and-the-martial-arts-part-1/

Image 1 above is from the Amar Chitra Katha comic “Ravana Humbled”

Image 2 above is from the Amar Chitra Katha comic “Veera Hanuman” (Kannada version)