February 17th is the Chinese New Year. This year is the year of the Horse, specifically, the Fire Horse. A search on the internet will reveal several pages and AI responses that mention several traits and attributes that a Horse, and more specifically a “Fire Horse” represents. But as a Hindu and a martial artist, the things that come to my mind when I think of a Horse as a symbol, are Knowledge and Martial culture.

When I think of a horse as an animal, things like speed, grace, strength, symbiosis come to mind, apart from history and, wait for it… confusion. Speed is of course synonymous with horses due to their ability to run over long distances. Modern horses, thanks to selective breeding practices, can be pretty large and therefore remind us of strength – think Shire Horses! Anyone who has watched any dressage or equestrian event will tend to agree that the gait of a horse is grace personified.

Horses have worked with humans for many millennia now and we have grown up on a staple of historical epic films and books showing horses and humans bond and participate in war and overcome travails – thus Symbiosis and History. Confusion is a trait specific to horses in Indian history I suppose. 😊There is a debate about when the horse was first present in India and if it was present during the Harappan civilization.

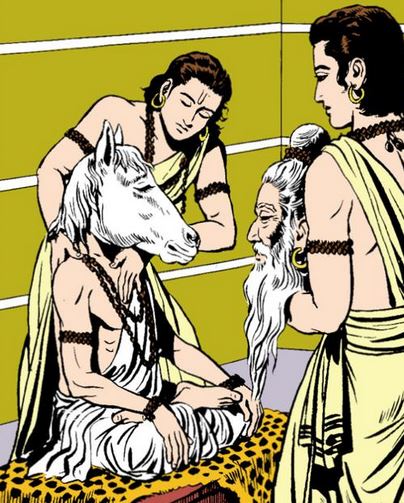

Now, when I think of the Horse as a symbol, the first thing that comes to mind is Lord Hayagreeva (sometimes spelled Hayagriva). “Hayagreeva” means “with the head of a horse”. Lord Hayagreeva is an avatāra of Lord Vishnu who is depicted with the head of a horse. Lord Hayagreeva, based on what I know, is always linked to Knowledge.

An image of Lord Hayagreeva. I unfortunately do not know who the artist of this image is.

This avatāra is not one of the well know Dashāvatāra. But Hayagreeva seems to be closely linked to the Matsya avatāra, which is the very first avatāra. The Matsya avatāra is the one when Lord Vishnu incarnated as a fish to save King Manu from the great flood at the end of a Kalpa. Some other important people, flora and fauna needed for the revival of civilization after the flood were also saved. This story is similar to other flood myths around the world.

The Fish imparted knowledge to the Rishis who were saved along with Manu so that they could use it in reestablishing civilization once the flood subsided. I have heard it said that this exchange of knowledge also became the origin of the Matsya Purana. Now there are 2 Hayagreevas I know of from the stories related to Age of the Flood.

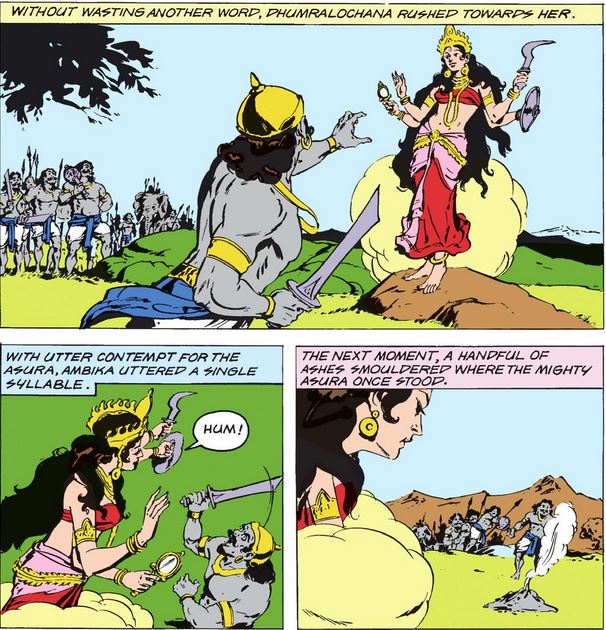

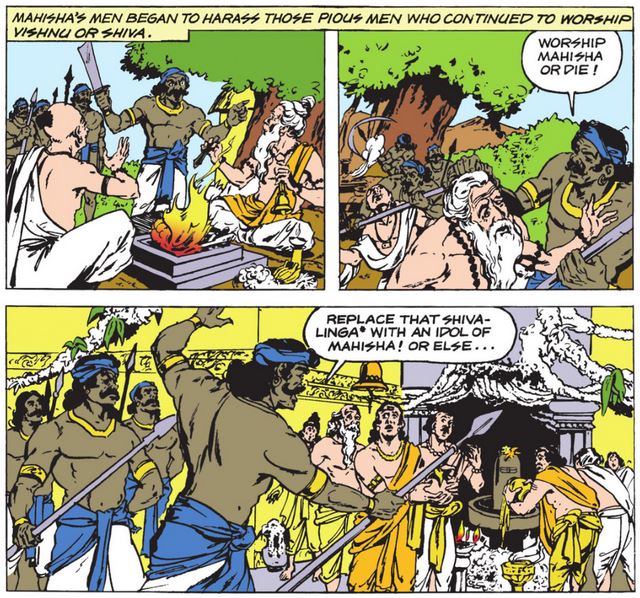

One is a an Asura named Hayagreeva, who also has the head of a horse. Hence, he can be referred to as Hayagreevāsura. The great flood was the time when Lord Brahma was resting before beginning the work of creating the new world after the flood. As he was resting, Lord Brahma yawned, and when he did so, the Vedas escaped his being. The watching Asura captured the escaped Vedas and hid himself in the waters.

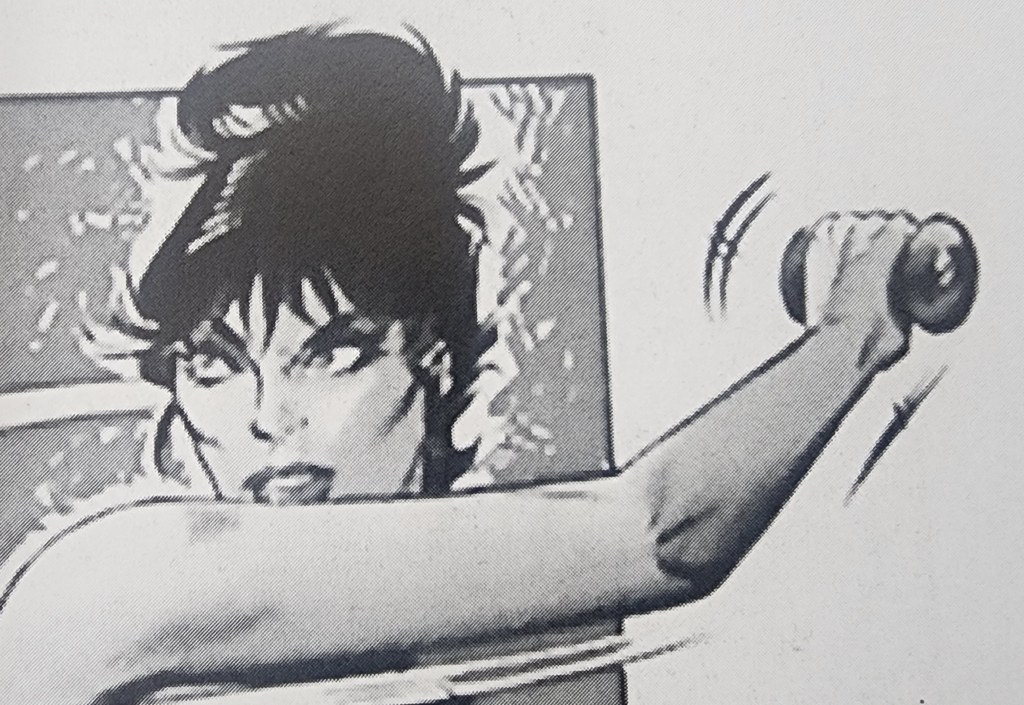

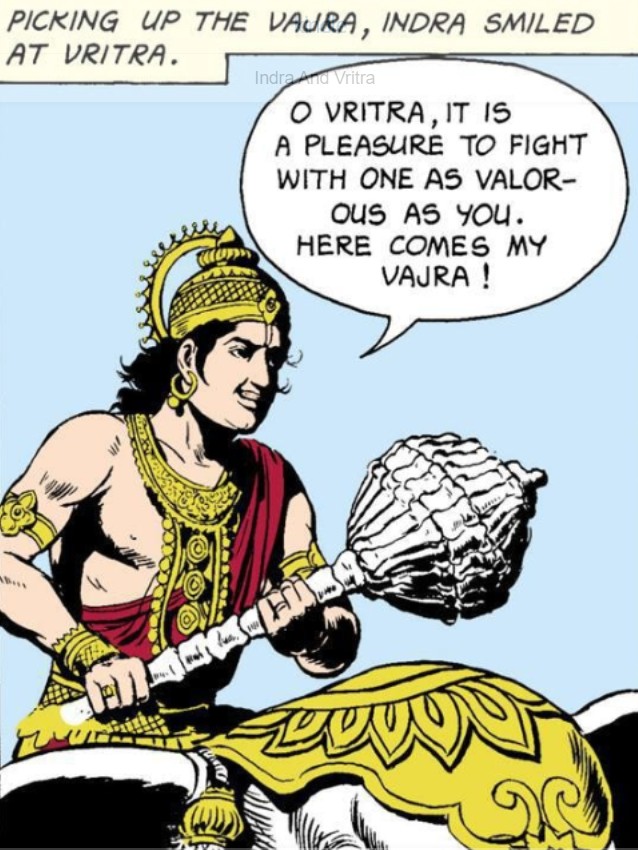

The Asura Hayagreeva. Image credit – “Dasha Avatar”, Kindle edition, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

The Vedas represent knowledge and wisdom. These are invaluable and can cause havoc in the wrong hands. The Matsya that saves King Manu also kills Hayagreevāsura, ensuring that the Vedas are safe. This is one case where Vedas, or Knowledge, are associated with the Horse.

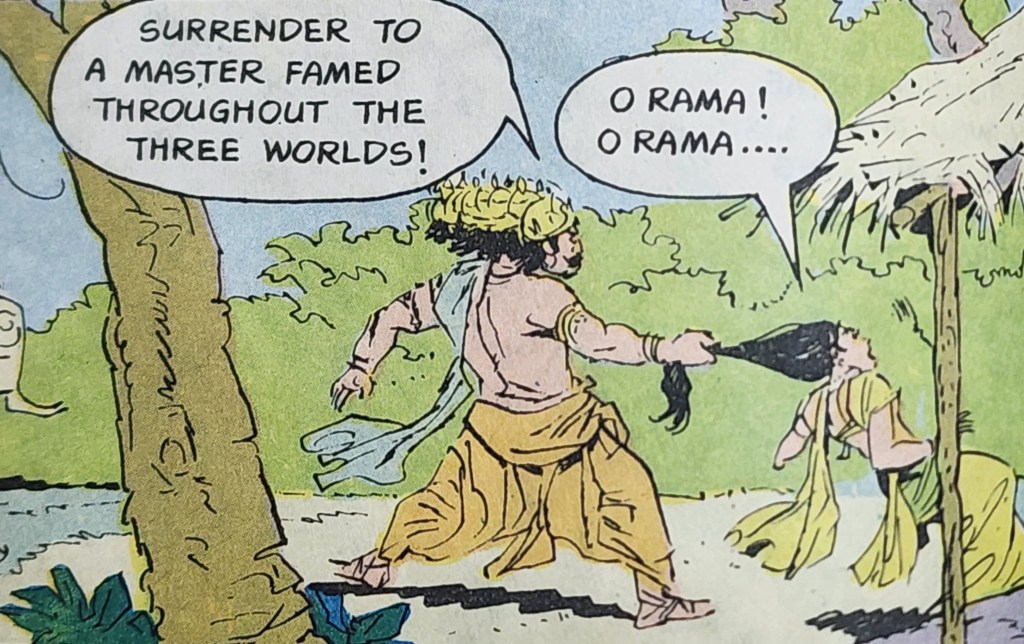

In another story, Lord Vishnu is in Yoganidra, the rest between epochs, during the time of the great flood. Two Asuras, Madhu and Kaitabha are born from his ear wax. There is a variation of this story where the 2 Asuras are created by Vishnu himself from a drop of water each. This is a callback to the fact that there is water everywhere at this time.

The Asura Madhu represents Tamas or darkness, supposed to be inertia that resists change. Kaitabha represents Rajas, the state of activity that represents restlessness tinged with darkness. These 2 Asuras gain a boon that they can only be killed when they so choose. With this protection, they go on to steal the Vedas and hide in the flood waters.

Lord Vishnu then takes the form of Lord Hayagreeva, the one with the head of a Horse to retrieve the Vedas. Even Lord Hayagreeva cannot defeat the Asuras due to the protection from their boon. In one story it is said that Lord Hayagreeva takes advice from the Devi, the original female deity on how to defeat the Asuras. Lord Hayagreeva praises the Asuras saying they are so great they even he cannot defeat them and hence would like to offer them another boon in appreciation.

But the prideful Asuras decline the offer and state that they would like to offer Hayagreeva a boon of their own. Using this opportunity, Lord Hayagreeva asks them Asuras how they can be slain. The Asuras are trapped and reveal that they can only be killed in a place where there is no water. This seems impossible to them since it was the time of the Great Flood and there was water everywhere.

But Lord Hayagreeva grows to a large size, lifts his leg out of the water, places the 2 Asuras on his thigh which is dry, and kills them. Thus, the Vedas are saved. In this story, it is again clear that the flood waters are a key component. Also, Lord Hayagreeva uses intelligence to defeat the Asuras. He tricks them to their doom, as physical effort alone will not suffice. Thus, the Horse (Hayagreeva) is again associated with Knowledge (Vedas), intelligence (get the enemy to reveal their weakness) and wisdom (ask for advice when actions are not working).

Seen above is a video from the YouTube channel, “Project Shivoham”. This video shares a lot of information about Lord Hayagreeva. There are several other videos on this channel which are very informative.

It must be noted that while knowledge is a key aspect, physical action is also vitally important in the two stories above; the Asuras have to be physically fought and defeated, there is no magic to circumvent that. And this point brings us to the other, very popular reference to the Horse in Hindu culture, that of the Ashwamedha Yajna.

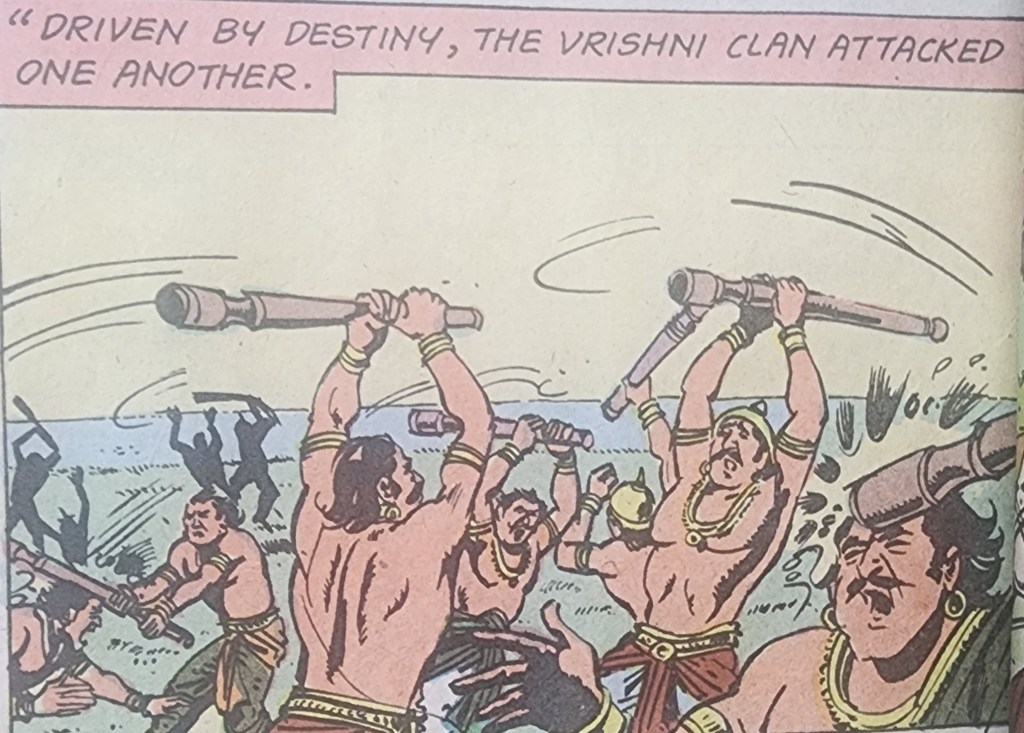

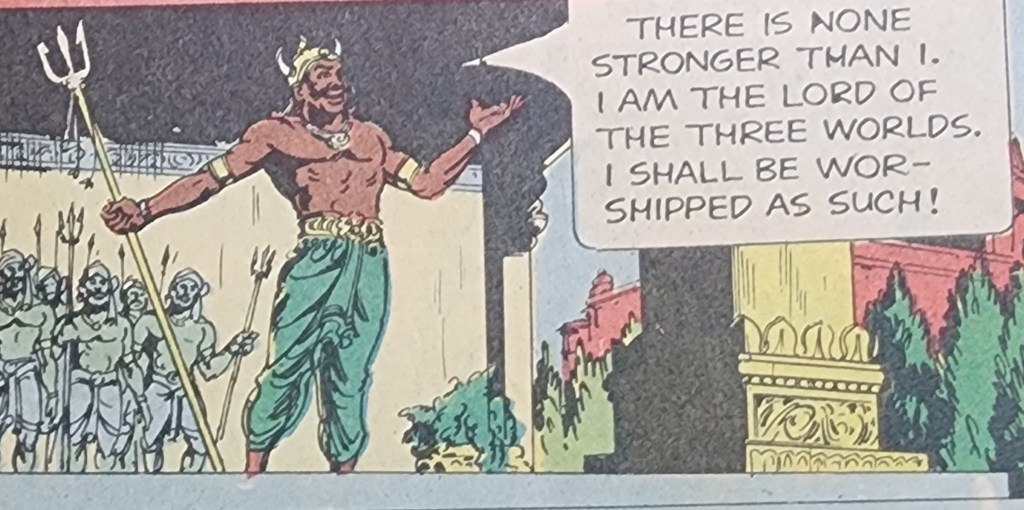

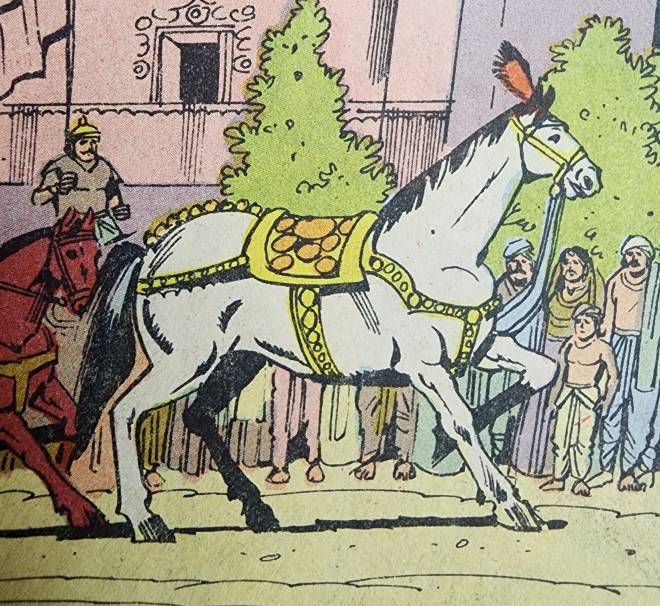

The Ashwamedaha Yajna is translated as “Horse Sacrifice”, but this seems simplistic. It is an activity that kings could use to expand territory and establish their superiority over other kingdoms. This Yajna was also a major economic activity! It involved having an excellent administration, supply chain, economy and military in place.

A large starting capital was needed to even consider the Ashwamedha. A military was needed to follow and protect the horse. A supply chain was needed to equip the military and conduct the Yajna. To manage the supply chain, an efficient administration was inevitable. So, the Ashwamedha Yajna, was a culmination of all civilizational activities! Which are the consequence of the Vedas that Matsya and Hayagreeva fought to protect!

Thus, the Horse (the Ashwa in Ashwamedha) is again associated with major civilizational activity, the centrepiece of which is war! And war is decidedly a martial activity, making the Horse reminiscent of the martial arts in Hindu culture.

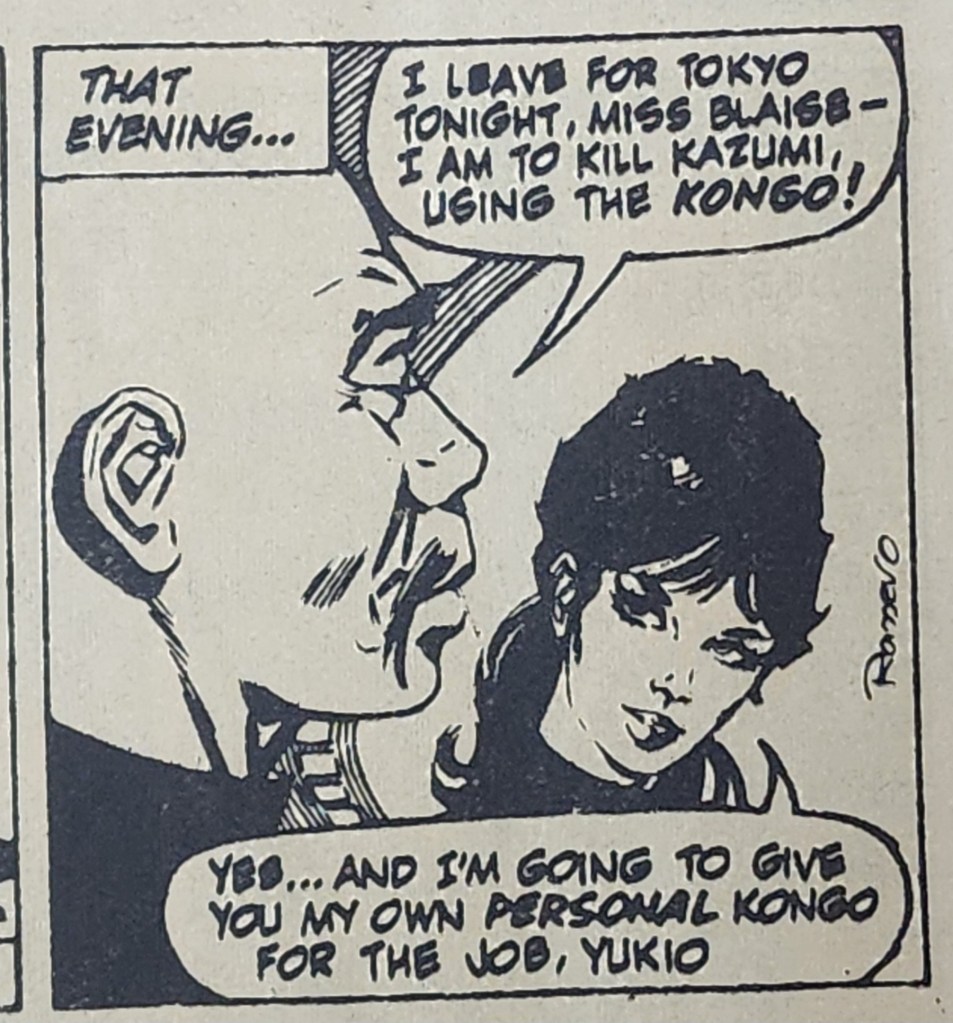

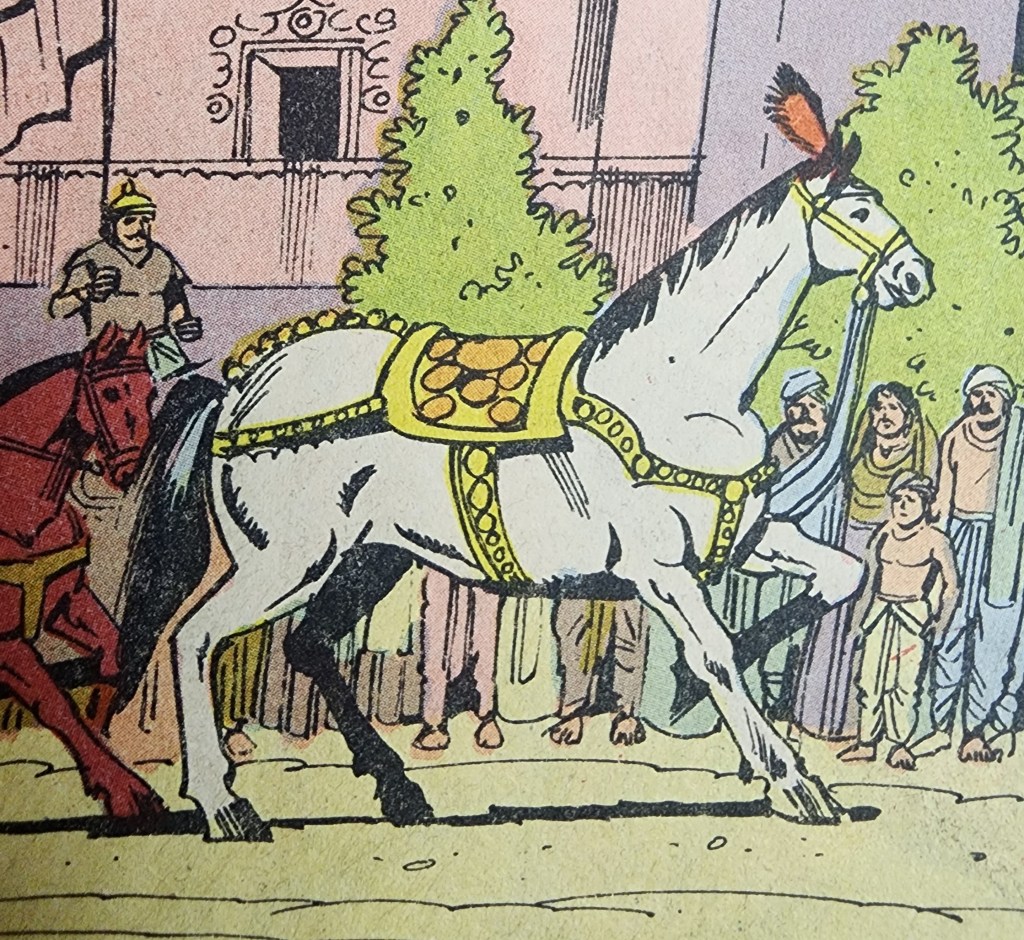

An image representing the Ashwamedha Yajna. Image credit – “Sons of Rama”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

The Ashwameda Yajna is part of the last segments of both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. If we go back to a time before the 2 Itihāsās (Ramayana and Mahabharata), there are a couple more references to the horse that ties it to the idea of knowledge and wisdom. These relate to the Rishi Dadichi and the Ashwini Devatas.

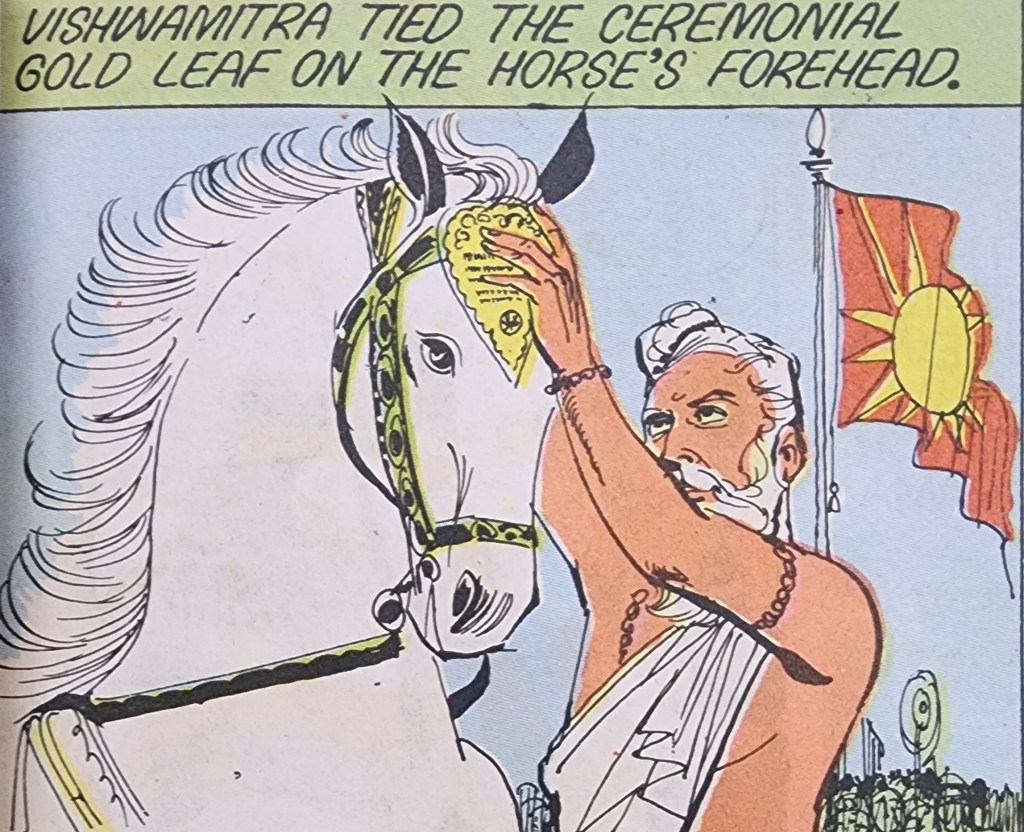

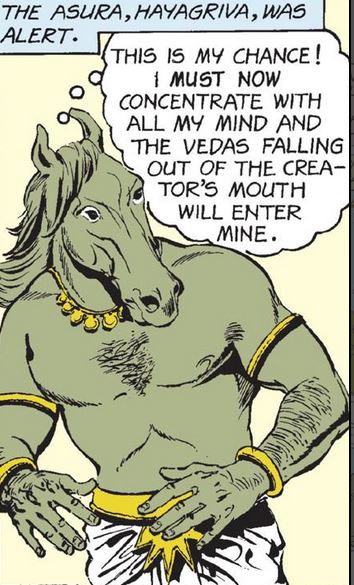

Rishi Dadichi is referred to as one with the “head of a horse”, or “Ashwashira” (Ashwa – horse, shira – head). This is supposed to be because he taught the Ashwini Devatas some secret knowledge. The association with knowledge and the horse is stark once again!

There is a one story where Indra, King of the Devas had decreed that anyone who passes on this knowledge will have their head explode. The Ashwini Devatas, wanted to learn this knowledge and Dadichi was the only one who was willing to risk Indra’s wrath. So, the Ashwins replaced Dadichi’s head with that of a horse. Once the knowledge was transmitted, his head exploded as per the decree.

But the head that exploded was that of the horse. The Ashwins, then attached the original head of the Rishi and Dadichi was brought back to life. This again shows the link between the horse, knowledge and sacrifice (like in the Ashwamedha Yajna, where the horse is sacrificed), which is a vital part of martial endeavours. In modern times, time, effort, money and other resources are expended in pursuit of the martial arts. In ancient times, all of these were still true, but more importantly, life and limb were on the line as well!

An image of a horse-headed Rishi Dadichi.Image credit – “Indra and Vritra”, Kindle edition, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

The Ashwini Devatas were twin Devas. They are considered the physicians/doctors of the Devas. This is why they were the ones that could replace the head of Rishi Dadichi with that of a horse and back. These twins, also referred to as “the Ashwins” were also historically associated with horses. I have heard it said that the “Ash” in the “Ashwins” is related to “Ash-wa”, which is the word for horse in Sanskrit, though I am not certain of this.

There is also a story from the Vedas, where the Ashwins device a prosthetic leg for Vishpala. Vishpala is generally considered a great female warrior, but there are some who say that Vishpala was a horse. Either way, they are supposed to have created a prosthetic leg all those millennia ago! And the reference is back again! 😊All of this adds to the fact that the Ashwins were indeed doctors. Doctors possess medical “knowledge” and the skills to save lives.

There is also a story where an individual on a voyage prays to the Ashwins when his ship sinks. The divine twins save his life and he returns home. Based on this story I had thought that the Ashwins were also the Gods of voyages. But the internet tells me that the Ashwins were more the deities associated with “a safe return home”! This does make sense, at least to me. The Ashwins were doctors and thus life savers, which dovetails nicely into “returning home safely”. The Ashwins, always associated with horses, possess the knowledge to save lives and get one home safely.

One last reference to horses that comes to mind from Hindu culture, considering that it is the year of the “Fire Horse” is that of Lord Surya, the Sun God. Lord Surya. Lord Surya is supposed to traverse the sky over the course of every day in a chariot. This chariot is drawn by 7 horses. These horses, drawing the fiery Lord that is the Sun, would represent the Fire Horse!

The charioteer of Lord Surya is Aruna, who is the brother of Garuda. Garuda is in turn the vāhana of Lord Vishnu. Vāhana can be translated as “vehicle” or “mount”. And we are back full circle to Lord Vishnu who we started with as Lord Hayagreeva. A horse is also a mount, either as the driving force of a chariot or as the momentum for cavalry. This detail gives a segue to the next part, where we consider the martial arts and history.

An image of Lord Surya on his chariot drawn by 7 horses, with the charioteer Aruna. This image is from Aihole, Karnataka.

What seems clear from the observations made above is that the horse is strongly associated with knowledge, and even wisdom, science and technology. But why would this be? I opine that this is because of the trait I mentioned early in this article in relation to horses – symbiosis.

When I use the word “symbiosis” here, it is more figurative than literal. I do not mean symbiosis like in the case of a lichen, where fungi and algae work together biologically. I mean symbiosis in the way a horse and its rider or handler work together as a team. Consider a show jumping event in the Olympics, where a horse, its rider and their teams work together as a single unit; that is what I am referring to.

Consider the history of the partnership between humans and horses. Horses have supposedly been domesticated for over 4000 years now. In that time horses have been used for a lot more than meat and milk unlike cattle. Horses, like oxen have also been used as beasts of burden in agriculture.

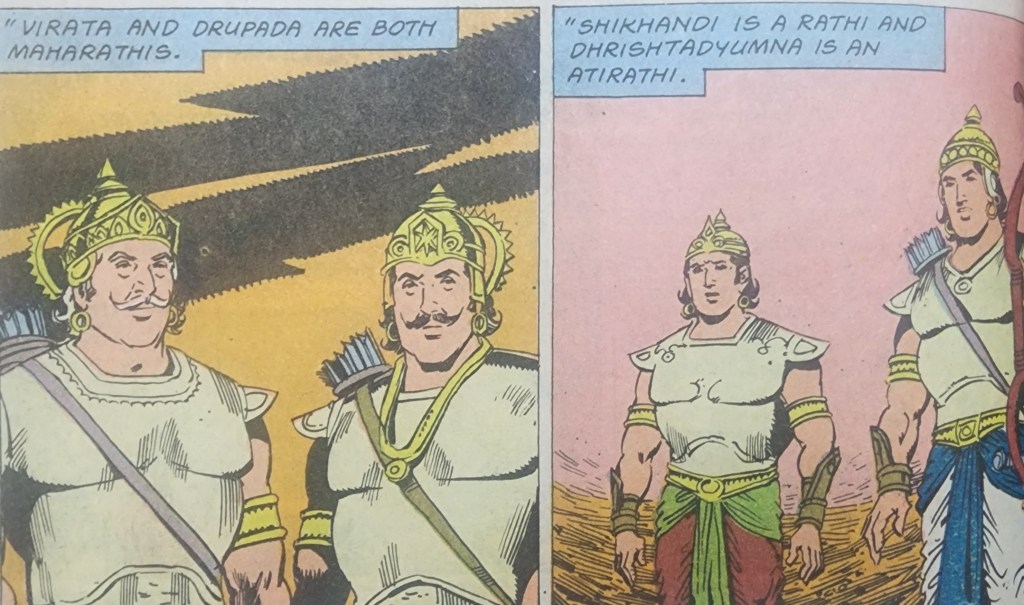

But arguably, the thing about horses that comes to mind for everyone is their use in war. Horses have been used with war chariots perhaps since the third millennium BCE. It is claimed by some that the oldest chariot found is from Sinauli in Uttar Pradesh, which dates back to between 2100 and 1900 BCE. Chariot warfare takes the centrestage in the Kurukshetra war of the Mahabharata.

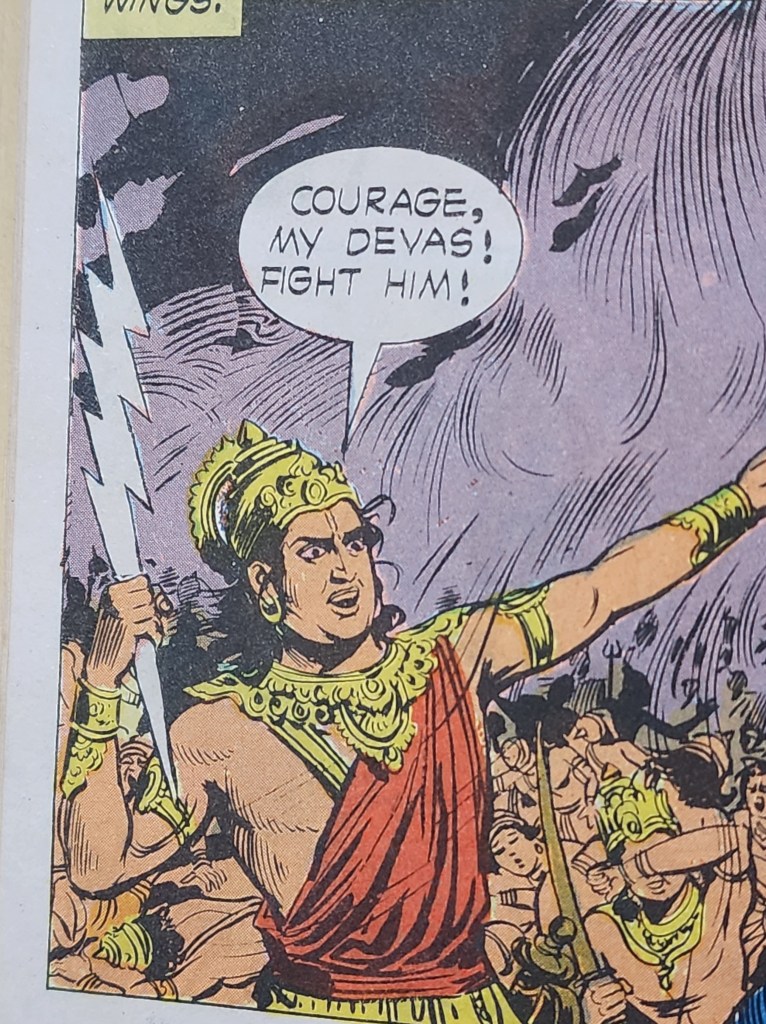

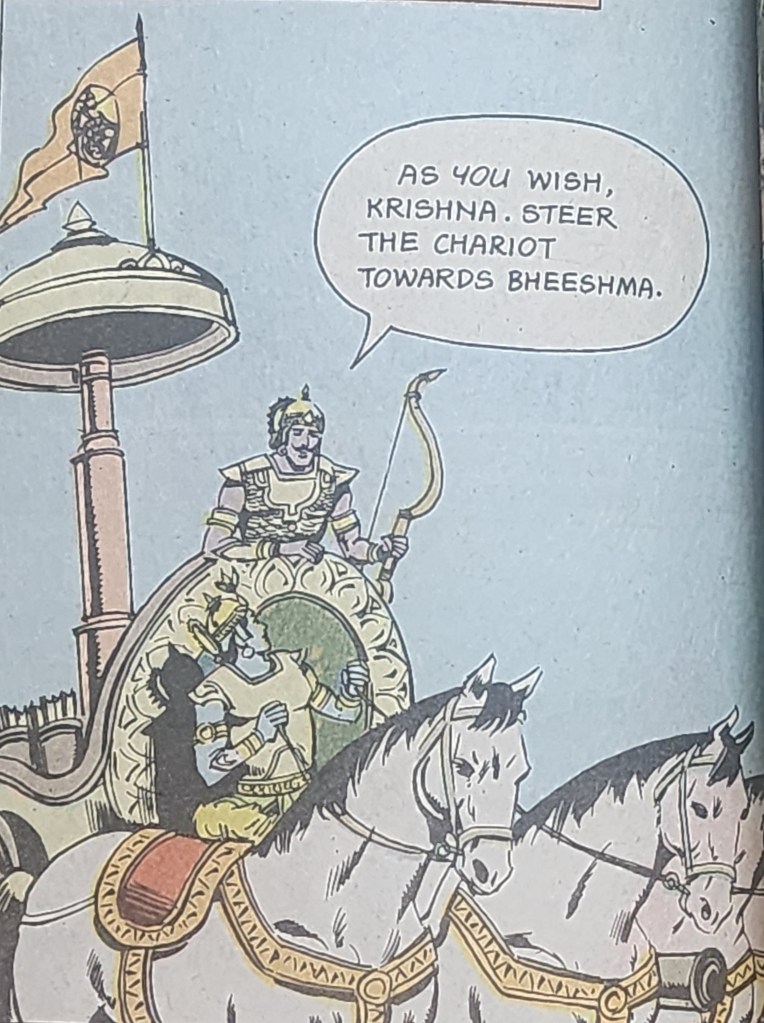

Warriors are ranked as “Rathi”, “Athirathi” and “Maharathi”, the last one being the highest rank! Ratha is the term in Sanskrit for chariot and a Rathi is one who fights in a chariot! So, the ability to fight from a chariot was a core requirement to be considered a great warrior! Charioteers were called “Sārathi”. Charioteers were held in high regard and some ended up being close confidants and advisors of the kings and nobles they served.

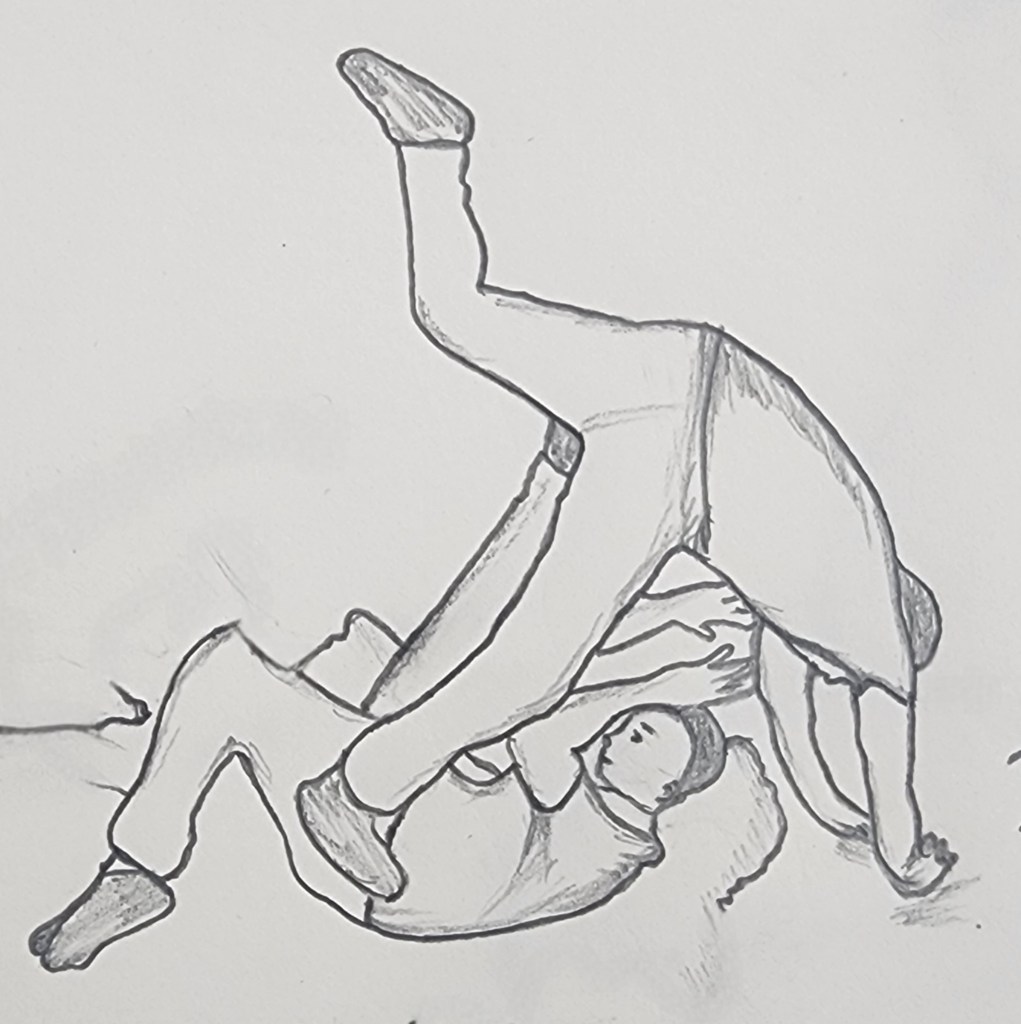

Image showing the categorization of warriors. Image credit – “Mahabharata 30 – The War Begins”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Chariots were also a key component of warfare in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia and in Europe. This is shown by the chariots of the Assyrian empire and the chariots mentioned in the Battle of Kadesh, fought between the Hittites and the Egyptians. Chariots were also used by the Celts when they fought the Romans.

An image of Lord Krishna as a charioteer. Image credit – “Mahabharata 32 – The Fall of Bheeshma”, published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Then comes the use of the cavalry, which started around the same time as the use of chariots, but lasted until the First World War! Cavalry was an active fighting force for 4000 years! Chariots diminished in importance by the beginning of the Common Era. The importance of cavalry kept increasing with the development of the saddle and the stirrup.

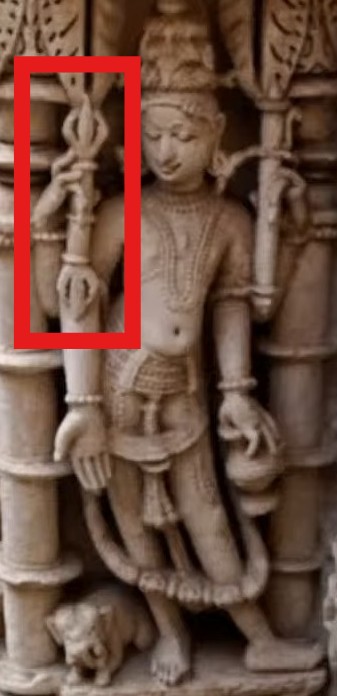

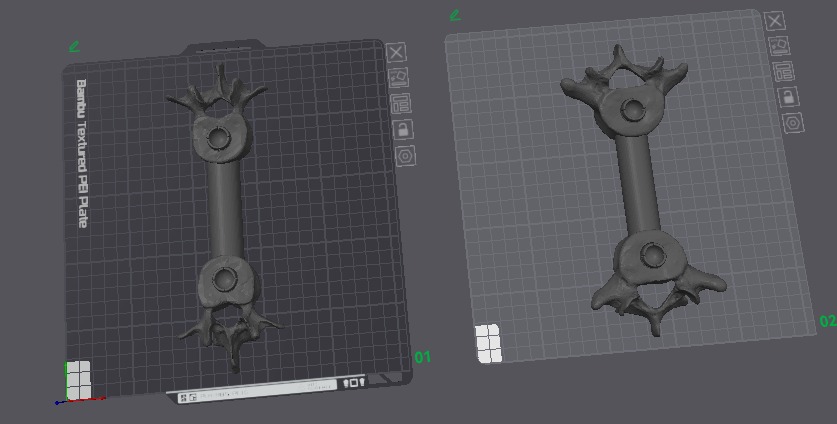

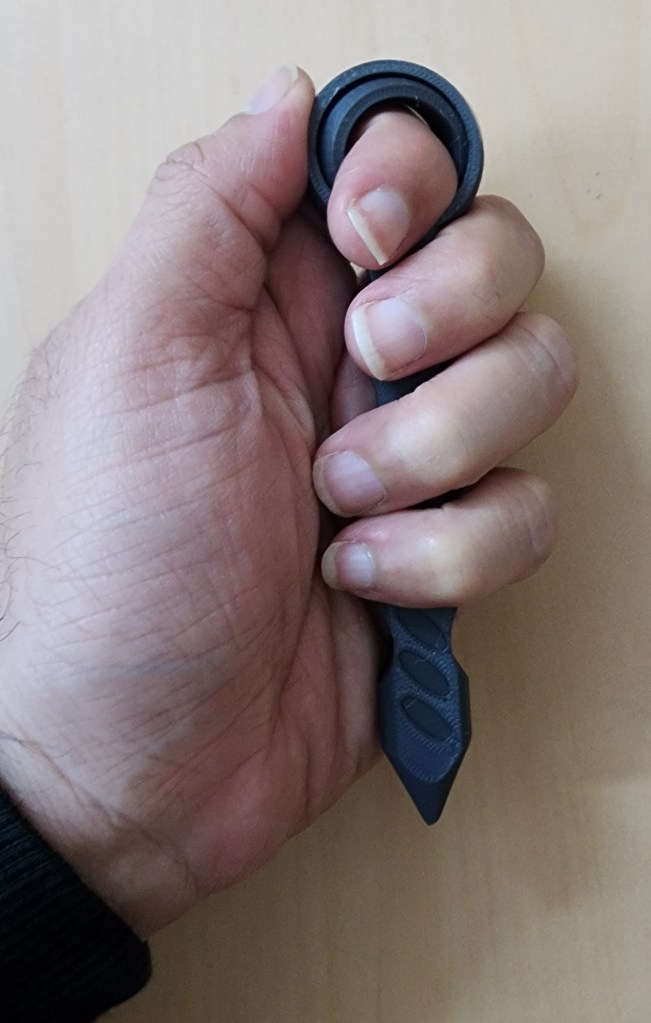

From the little that I know, the stirrup could have its origins in India around 200 BCE, in the form of a “toe stirrup”. The earliest visual representation of the stirrup is supposedly from the Toranas (gateways) of the Great Stupa at Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh, India.

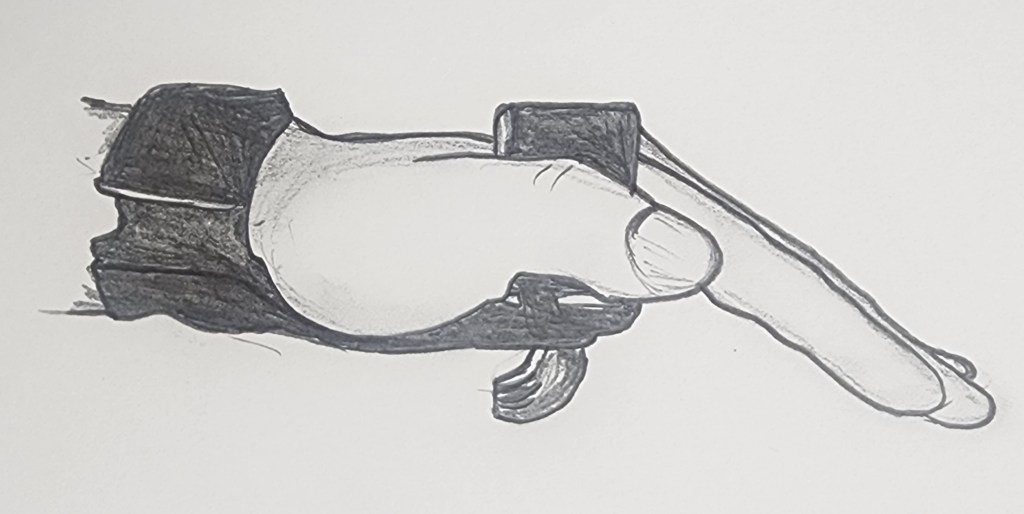

Two images from the Toranas (gateways) of the Great Stupa at Sanchi, that could be representations of stirrups. The first image could be “toe stirrup”. The second image could depict a stirrup, or a person relaxing his feet, I am not sure.

With the importance of cavalry growing, the selective breeding of horses improved and developed continuously, with horses reaching the massive sizes they reach today! The combination of the composite bow with cavalry made the Central Asian peoples a superpower for more than a millennium, starting with the Scythians (Shaka in India) and gong all the way to the Mongols and then the Mughals of India.

One of the most impactful examples of the use of cavalry from Indian history is from the Second Battle of Tarain in 1192 when Prithviraj Chauhan was killed and the Delhi Sultanate was seeded. The armies of Ghori who won this battle, are supposed to have succeeded, partly due to their cavalry tactics, which they used to avoid close quarter battle against the Rajputs, which led to their defeat a year earlier in 1191, in the First Battle of Tarain.

The armies of Ghori were Turkic people (not Turkish) who used the Central Asian way of fighting. They supposedly used something called the “Parthian Shot”. Units of Turkic cavalry used to run in circular formations at the distance of a bow shot from enemy formations and rain arrows down on the enemy. This was used to grind down the enemy while denying the opportunity to close distance and engage in hand-to-hand combat. This tactic was something the Rajput army supposedly did not have a response to.

This link leads to a YouTube video which gives a lot of detail about the Second Battle of Tarain; a part of the video describes the “Parthian Shot” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHMMwLGI0xM

The last cavalry charge in world history also involved Indians. The Mysore and Jodhpur Lancers played an instrumental role in the Battle of Haifa in 1918, when Haifa was captured from Ottoman control during the last part of the First World War. I have heard that the cavalry became a ceremonial unit after this last hurrah.

The little information about cavalry in the previous paragraphs brings me to the point about the relationship between knowledge and the horse. Think of all that needs to happen for a cavalry to exist.

- Horses are needed in considerable numbers. So, they need to be bred.

- Horses need to be raised and cared for.

- Horses need to be trained.

Even if states in the past expected cavalrymen to provide their own horses, raising a cavalry would require a sufficient number of the populace to have the knowledge and skills to breed, raise, train and equip horses. Each of these activities needs knowledge and experience to be accumulated over generations and passed on, even improved over time.

Let me reinforce this with an anecdote. A senior practitioner in the Bujinkan and friend of mine used to be an equestrian. He had competed at the European level and was considered a very good horse rider. He was asked how he trained the horses he rode. He said that he does not train horses. This was a surprising answer for a lot of us who had never worked with horses.

We then asked how the horses were trained. He then said that he does not know! Seeing our surprise, he explained with an analogy. He said that a great Formula 1 driver, say Michael Schumacher, would not be able to service his F1 car by himself. He would most certainly not be able to build his own car! In the same manner, a horse rider would learn to bond with, work with and achieve great feats with a trained horse, but he would not be able to train the horse by himself or herself. He would not be able to care for it by himself or herself either! The knowledge and skills required in each of the activities is extensive and always needs experience and teamwork.

I think the above anecdote demonstrates how knowledge and experience are key to working effectively with horses. This would have been far more important in the past when cavalries were vital on battlefields. Was this the reason horses came to be associated with knowledge? I would say yes, even though I do not know what mainstream history says.

I mentioned what it takes to have horses available to be a part of a cavalry. Now consider what it takes to be a cavalryman or woman.

- One needs to ride a horse

- One needs to be able fight on horseback

- Be able to stand in the stirrup when needed

- Shoot an arrow while riding

- Twist in the saddle to shoot at different angles (imagine shooting backwards while riding full tilt!)

- Use a lance while riding

- Use a sword while riding

- Use weapons while keeping formation with fellow cavalrymen! And this could be with Heavy Cavalry or Light Cavalry!

- Lest we forget, these soldiers had to be able to use their weapons on foot if they were to lose the horse! And the manner of using a lance or a sword on foot and on horseback is vastly different!

An image of a horse archer (likely Turco-Mongol)twisting in the saddle to shoot backward while riding forward. Image credit – Wikipedia.

Each of these aspects, over time, developed with variations in cultures and geographies. So much so that different schools and methods formed over time. This shows how knowledge and experience coalesced over centuries in the ability to fight as a cavalry unit. I have not even touched upon the creation and use of armour and shields for the soldier and the horse when they fight as a unit! This should lend further credence to the idea that the need for knowledge to work with horses led to the horse being a symbol for knowledge.

In the Bujinkan system of martial arts we do not train horse riding or fighting from horseback as part of the curriculum. But Bājutsu, which refers to cavalry techniques, is historically one of the 18 segments of Ninjutsu. There is another concept that is reinforced regularly in the Bujinkan – “Shu Ha Ri”. This idea also reinforces why I opine that the horse was associated with knowledge in India.

- “Shu” roughly translates to diligently learning techniques, ideas and concepts

- “Ha” refers to training what was learnt until it is completely assimilated and works for the individual

- “Ri” refers to the phase when an expert goes on explore new possibilities with the expertise that was gained through long experience

This is true for the martial arts, when a student repeats the same movement until it becomes second nature. The student then goes back to the basics, every once in a while, iteratively, while going on to add more to her or his repertoire. After a considerable period of indulging in this cycle, the student goes on to explore different expressions of the abilities gained through the years of training.

This cycle of “Shu Ha Ri” is applicable for most skills learnt over the course of one’s life. If one considers the points I mentioned relating to cavalry earlier, there would be a “Shu Ha Ri” cycle to creating a horse ready for war and another “Shu Ha Ri” cycle to create a warrior who can work with the horse!

The “Nin” in Ninjutsu refers to “perseverance”. The “Shu Ha Ri” mentioned above is all about endurance. One needs to be able to expend time, effort and money over years to become a good martial artist; or to be good at anything. This again shows how knowledge is earned over time with great effort, not unlike how humankind achieved great things while working with horses. Is it then any surprise that Indians have a God who is represented by a Horse?

I will end by saying that in the Indian context a lot of what I mentioned holds true for elephants as well. And sure enough, we have a God who is depicted with the head of an Elephant! This is the most frequently worshipped Lord Ganesha! Lord Ganesha is worshipped as “Vighnahartha”, the “remover of obstacles”. Lord Ganesha is also worshipped as “Vidya Ganapati”, “the one how enables learning”. “Vidya” can also be translated, in common parlance, as “education” or “knowledge”. Removal of obstacles requires knowledge as well! And that shows how yet another animal which is vitally important in Indian history is also used to represent divinity.

An image of Lord Ganesha

Interestingly, there is sweet dish made in parts of India called “Hayagreeva”. 😊It is prepared during festivals, but not any specific festival. It is more likely to be made during the Dasara (Dussehra) festival, one of the days of which, in my community, is dedicated to Lord Hayagreeva! The dish is made of gram, jaggery, ghee and grated coconut. I have no idea how the dish came to be named after a God! 😀

The delicious sweet dish, Hayagreeva.