Vijayadashami is the last day of the Dasara (Dussehra) festival. One story associated with Vijayadashami is the victory of Devi Durga over Mahishāsura. Vijayadashami is the 10th day of the Dasara festival. The 9th day is celebrated as “Āyudha Pooja”. Devi Durga could wield all weapons expertly and this is part of the reason for the festival of “Āyudha Pooja”. Āyudha can be translated as “weapon” and this festival is all about showing gratitude to the tools that enable us to live and prosper.

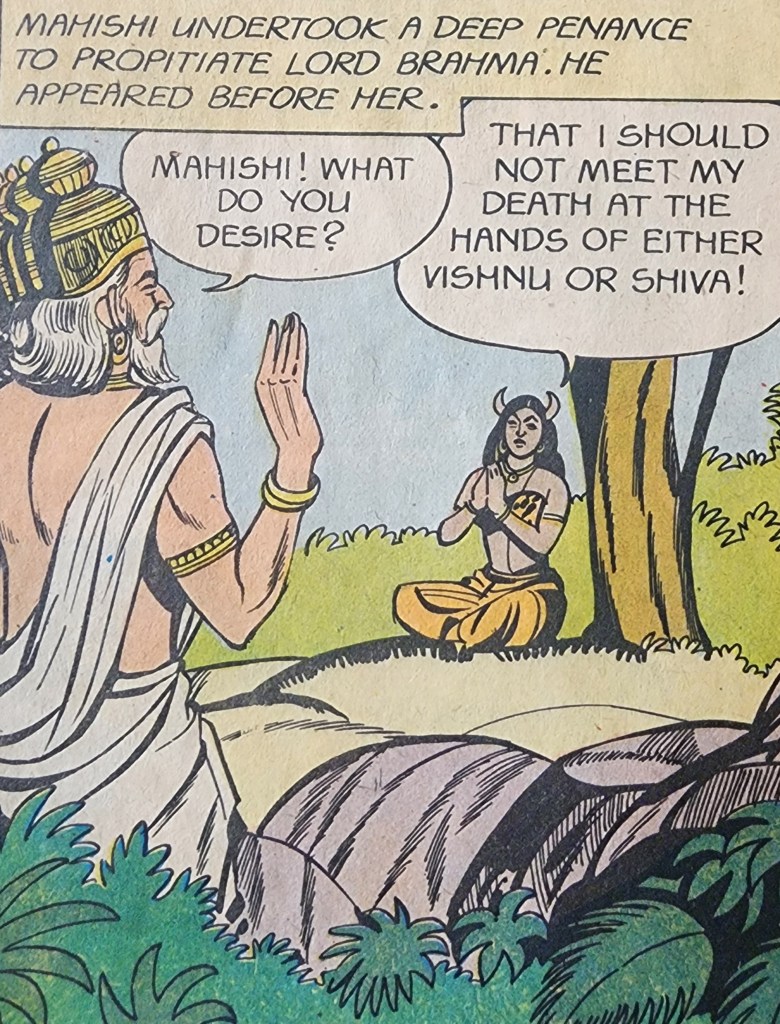

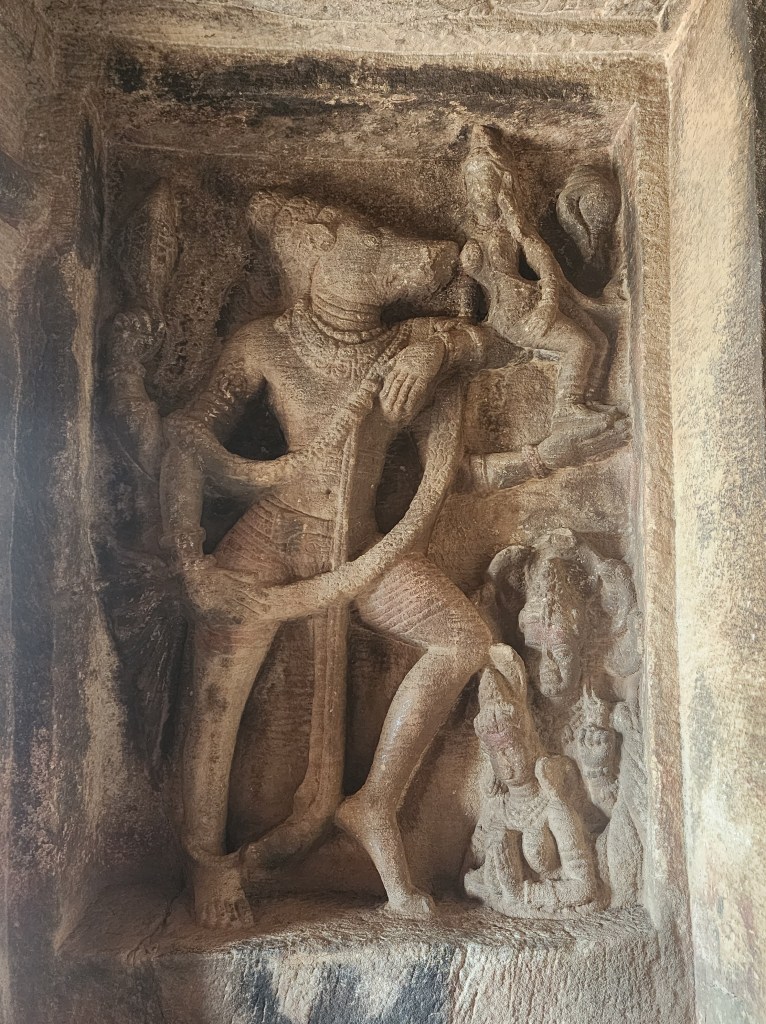

Mahisha was an Asura (more specifically a Dānava) who had shape shifting abilities. He had acquired a boon from Lord Brahma after a severe penance that ensured that he could only be killed by a woman. This meant that none of the Devas or Lord Vishnu or Lord Shiva could kill him. He believed no woman, including the female personifications and consorts of the Devas could ever defeat him, let alone kill him, and hence his choice of the boon.

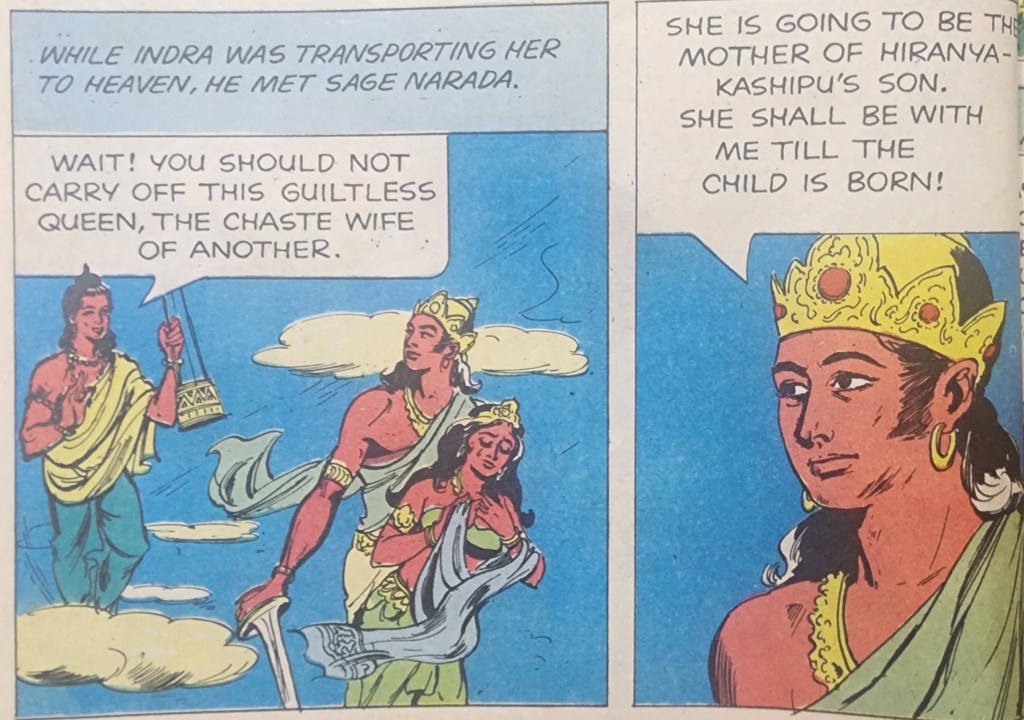

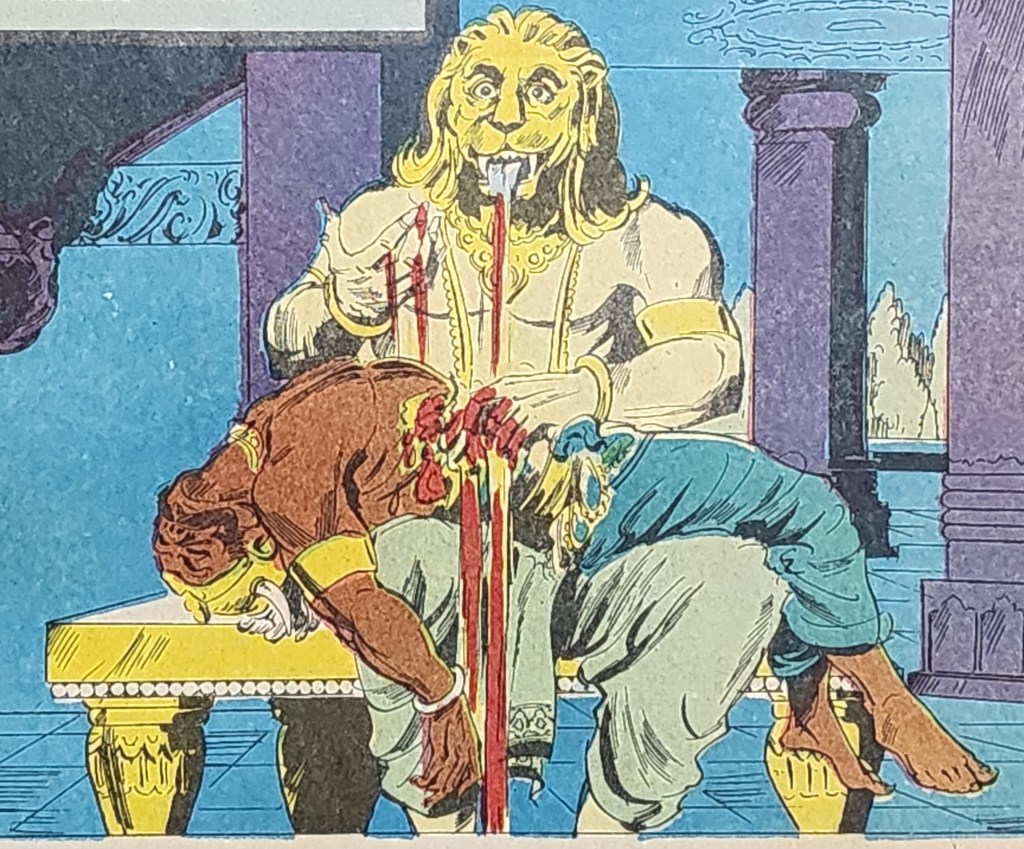

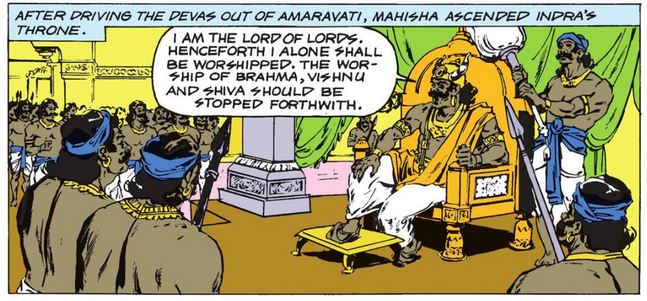

Mahisha gains a boon, which allows only a woman to defeat and kill him. Image credit – “Tales of Durga” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Armed with his boon, Mahisha defeated the Devas, conquered Swarga (loosely translated as Heaven) and its capital Amaravati and enforced monotheism on all humans in the world. This caused chaos and threw the natural order (Rta) out of balance. The Devas are the guardians of the 8 directions and natural phenomenon and could no longer perform their duties. To remedy this situation, Devi Durga was born. She was granted the use of all the weapons of the Trimurthy and the Devas. This is why Devi Durga is associated with weapons as she is the only who possesses and expertly wields all of them.

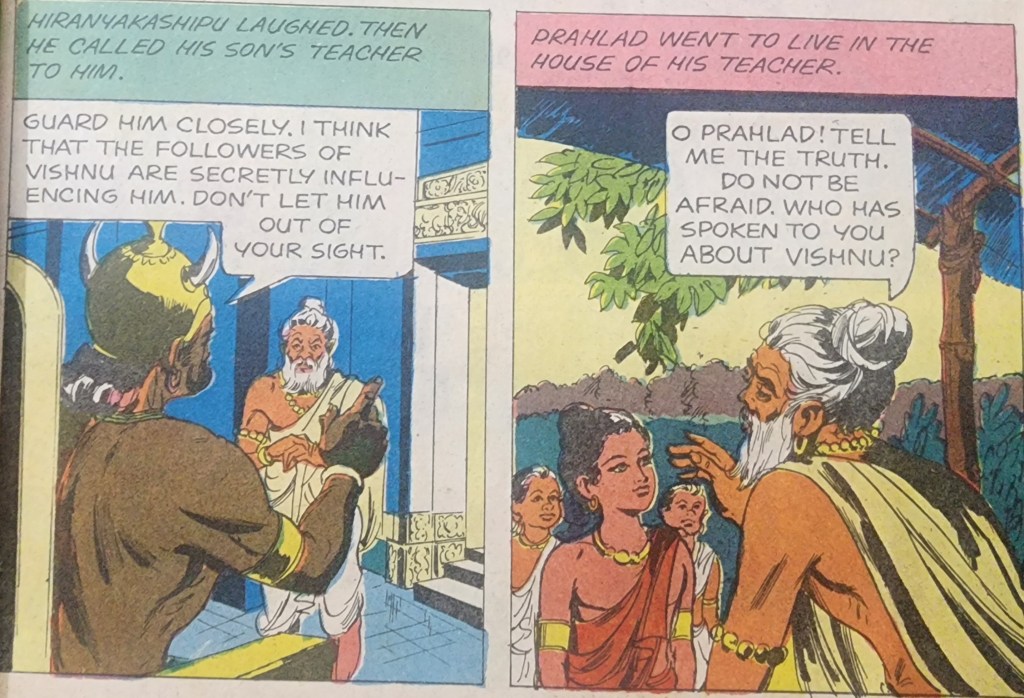

Mahisha imposes monotheism. Image credit – “Tales of Durga” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha.

Eventually Devi Durga fought Mahishāsura and killed him, restoring peace to the entire world. She used all the weapons she had access to while fighting Mahisha and his army. The actual act of Durga killing Mahisha is the subject of art and iconography in all parts of India. This has been the case for close to about 2 millennia or more now. The act of Durga killing Mahisha is called “Mahisāsura Mardhini”. The crux of this article relates to the depiction of how exactly Durga killed Mahishāsura as seen in different representations of the “Mashishāsura Mardhini”.

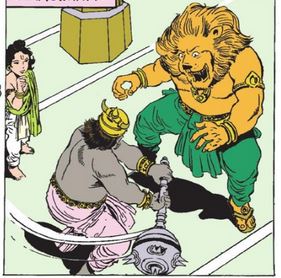

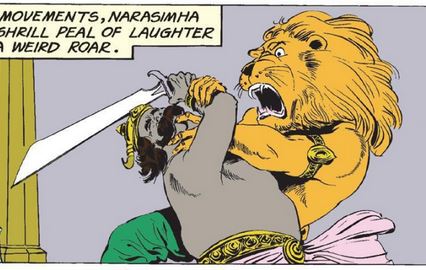

Durga beheads Mahisha. Observe the sword, it is not a typical talwar, it is a dedicated chopping sword. Image credit – “Tales of Durga” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha.

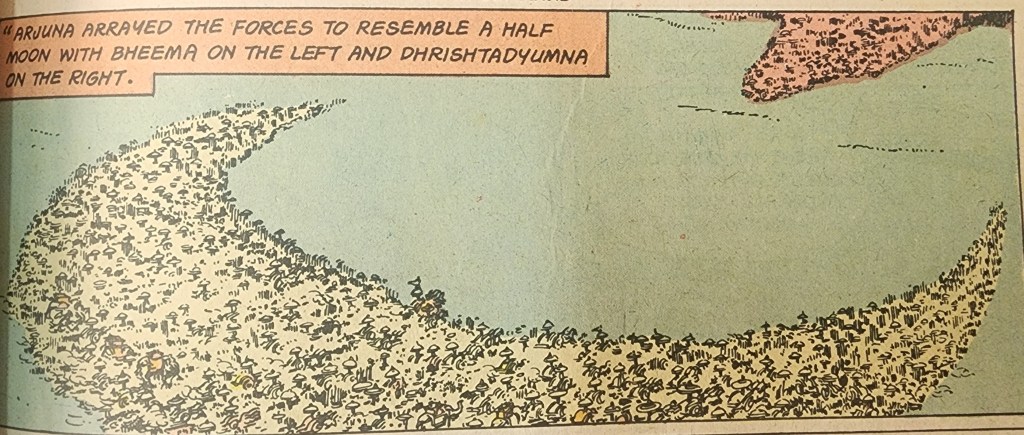

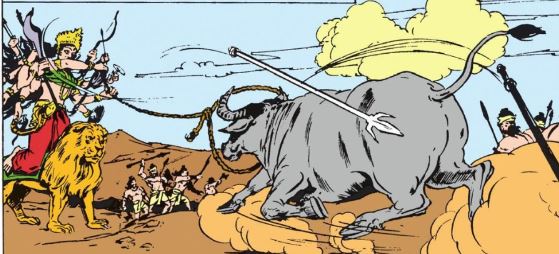

The depiction of Durga killing Mahisha that I came across as a child was in the Amar Chitra Katha comics. Here, she is depicted as killing Mahisha with a sword. She beheads with him with a sword. The sword shown in the comic was a chopping sword and not the typical talwar. The most interesting aspect of the artwork in Amar Chitra Katha is the depiction of Durga using a noose to subdue Mahishāsura! The noose, called a “Paasha”, is the weapon associated with Varuna, the Lord of the waters and oceans. He is also the Guardian of the West.

Devi Durga subdues Mahisha in the form of a buffalo, with a noose (Paasha). Image credit – “Tales of Durga” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha.

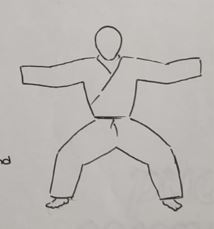

But in the past, Durga is seen subduing Mahisha with a Trishoola (trident). She is also depicted fighting the Dānava with archery. For the purposes of this article, I will specifically refer to the depictions of the Mahishāsura Mardhini in the architectural marvels of the Vatapi Chalukyas in Karnataka and those of the Pallavas in Tamil Nadu. The carvings of the Chalukyas I will refer to are those from Badami, Aihole and Pattadakal. The creations of the Pallavas referred to are in Mahabalipuram. The sculptures from both states are from roughly the 6th to the 8th centuries.

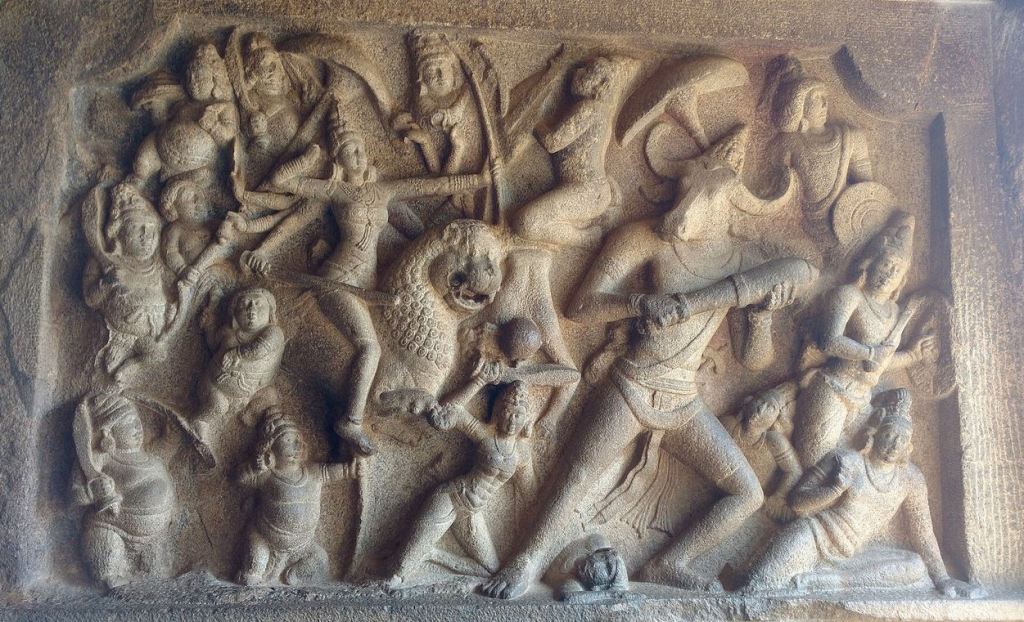

Durga fighting Mahisha, as depicted in the famous panel at Mahabalipuram. Image credit – Wikipedia.

The carving at Mahabalipuram depicts Durga seated on a lion and fighting with a bow. Here Mahishāsura is shown in an anthropomorphic form. He has the head of a buffalo (which is what Mahisha means) and the body of a man. He wields a large club. A version of this carving is also seen in Pattadakal. It is seen on a small panel in one of the temples at the Pattadakal temple complex.

A depiction in Pattadakal similar to the one in Mahabalipuram.

In Aihole, there is a cave temple called “Ravana Phadi” (in some sources it is referred to as “Ravala Phadi”). In this cave, there is a stunningly beautiful depiction of the Mahishāsura Mardhini. In this sculpture, Mahishāsura is depicted as a buffalo. Durga has subdued him with one knee and speared his body with a Trishoola. There are similar depictions in both Pattadakal and Badami. There is yet another depiction of the Mahishāsura Mardhini in Aihole, at the temple complex.

Mahishāsura Mardhini depicted at the Ravana Phadi cave temple in Aihole. Observe the area encircled in white. The spike at the rear end of the Trishoola is used to stab Mahisha.

This is a closeup of the area encircled in the previous image. The spike of the rear end of the Trishoola going through the buffalo is clearly visible.

In the depiction at Pattadakal Mahisha is depicted in an anthropomorphic form, but different from the one made popular by the depiction at Mahabalipuram. Here the sculpture is partially damaged, and Mahisha seems to me like a man with small horns. Here, Durga has run through the Asura not only with her Trishoola, but also with her sword.

Mahishāsura Mardhini depicted at Pattadakal. Mahisha has been stabbed with the sword and also the rear end of the Trishoola. The trident of the Trishoola is encircled in white; this shows that the rear end is doing the stabbing.

In the Badami museum, situated within the cave temple complex, there is a small panel, which shows Mahisha as a buffalo proper. Here again, the Asura is speared by Durga’s Trishoola. In the depiction at the Aihole temple complex as well, Mashisha is a buffalo and has been slain by Durga’s Trishoola.

Mahishāsura Mardhini in a carving at the Badami museum. This also shows the rear end of the Trishoola doing the damage. The trident and rear spike are seen in the highlighted boxes.

The most interesting part in the depictions at Aihole, Badami and Pattadakal is the part of the Trishoola with which Mahishāsura is speared! Devi Durga has thrust through Mahishāsura with the rear end or the butt of her Trishoola! As a martial artist, this is an incredibly interesting aspect!

Mahishāsura Mardhini as seen in the bas relief at Chabimura, Tripura. This also shows the rear end of the Trishoola being used. This carving is from the Northeastern part of India, while the others were from the South. This carving is supposedly from the 15th or 16th century. This shows that the rear end of the Trishoola being used was shown across a vast geography over at least a 1000 years!

The bas relief at Chabimura seen in its entirety. The carving itself is over 20 feet tall and is situated on a cliff face on the river Gomati. The carving is over 20 feet off the ground.

This depiction of course is not always used. There is a carving in the Aihole museum where Mahishāsura is being stabbed with the trident part of the Trishoola. But that seems to be exception at this time and in this part of the world, based on the depictions I have seen. And the fact that the rear end of the Trishoola is used as the part that is causing the damage is what inspired this article.

A carving at the Aihole museum of the Mahishāsura Mardhini depicts the use of the trident instead of the rear spike as seen in the encircled area above. The rear end of the Trishoola is damaged and not clearly visible.

The Trishoola is a pole arm. Pole arms are weapons that are mounted on a shaft or haft, usually made of wood. They are generally as tall as or taller than the individual wielding it. The length of the weapon gave a great range/reach advantage when the weapon was used, either for hunting or in war. Some well-known pole arms are, the spear in its various forms, the glaive, the poleaxe, the halberd in its various forms, the pike, and even the man-catchers!

In the Bujinkan system of martial arts which I practice, the commonly practiced pole arms are the Naginata and the Yari. The naginata is the Japanese equivalent of a glaive or a halberd. The yari is the term used for different forms of the spear in Japan. The man-catcher is called a “Sasumata” in Japanese. Another example of a Japanese pole arm is the “Sodegarami”, which was a pole arm used against Yoroi (Japanese armour).

Historically, many pole arms have used a butt cap at the end of the shaft or haft. This added a bit of weight at the rear end of the weapon. The two commonly used forms of the butt cap was a spike or a sheath, like a cladding. The main function of the spike or the cladding was to reinforce the wood that made up the shaft, to protect the end from splitting and other like damage. The weight that a spike or cap possessed could act as a counterweight. In this role it helps maintain the centre of gravity of the weapon and balance the weight of the blade, spearhead, hammer, billhook or anything else at the business end of the weapon.

Representative Naginata and Yari (spear). The Yari has a simulation of the Ishizuki, while the Naginata does not. This is seen within the boxes in red.

In the case of a Yari or a Naginata, the weight (likely metallic) at the end of a Yari or Naginata can be of two kinds. One is the “Ishizuki” and the other is the “Hirumaki”. The “Ishizuki” can be translated as a “weight with a point”. It is essentially a spike. “Hirumaki” can be translated as “Big Roll”. Here the “Roll” in “Big Roll” is something that is used as a wrapping. The “Hirumaki” is essentially a cladding or a sheath of metal which adds weight.

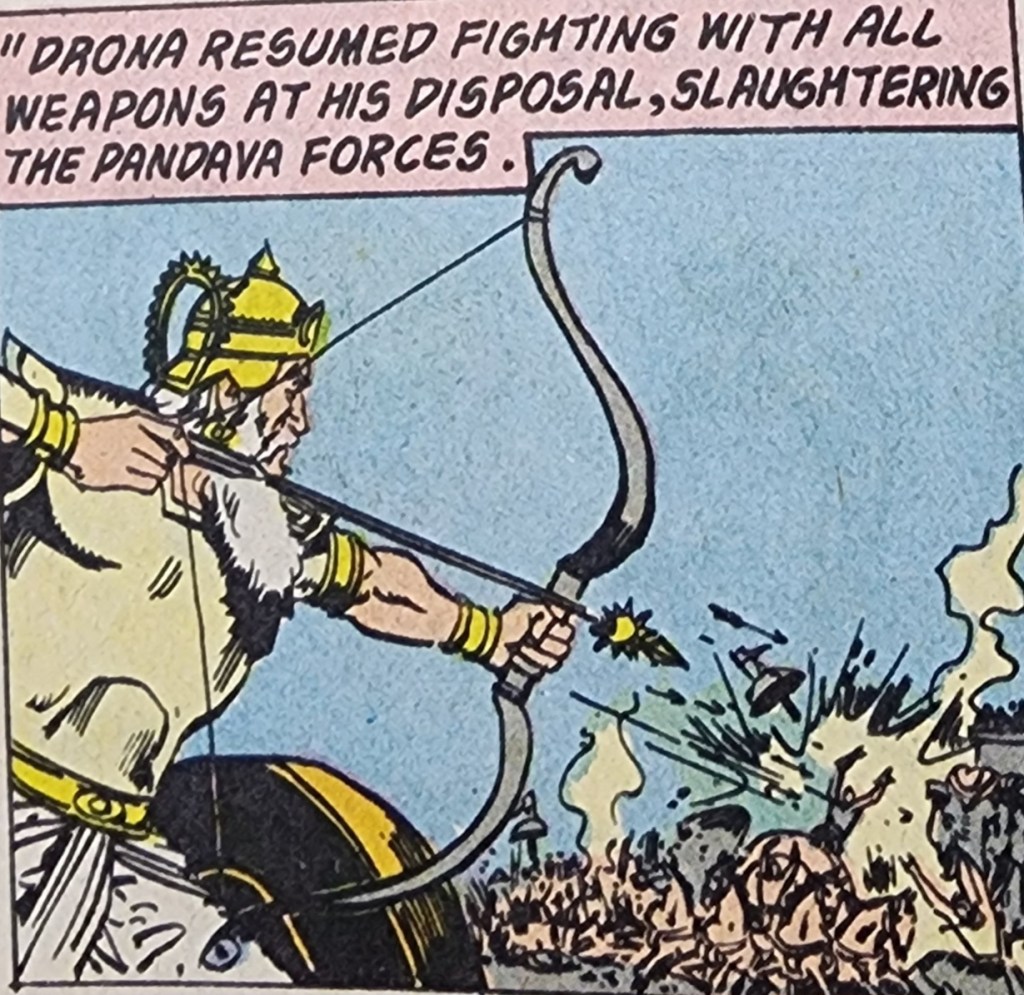

The above images show Lord Shiva slaying Andhaka with his Trishoola. In the image on the left, observe the rear end of the Trishoola, encircled in white. It is not a spike as seen in the earlier depictions of the Mahishāsura Mardhini. The rear end here is like a cladding or a pommel. This is a representation of the “Hirumaki”. The close up on the right shows that Andhaka has been stabbed with the trident (encircled in white). Could this indicate that of there was a spike or Ishizuki on the Trishoola, it was the offensive part, but if there was a Hirumaki or pommel on the Trishoola, the trident was the offensive part?

So, it is likely that the Trishoola too, being a pole arm, had a weight at the end of the shaft. This weight was quite likely a spike. The spike at the rear end of a pole arm was not the primary weapon. But it was definitely used in fighting, simply because the rear end of any pole arm can be used to strike an opponent or to block an attack. This happens when the attack from the spearhead or blade or trident is blocked and disengaging from the opponent’s weapon is not immediately possible.

A representation of a spike or Ishizuki on a Trishoola (inside the box in red).

A representation of a Hirumaki/cladding/pommel/wrap/sheath on a Trishoola (inside the box in red). Image credit – “Tales of Durga” (Kindle edition), published by Amar Chitra Katha.

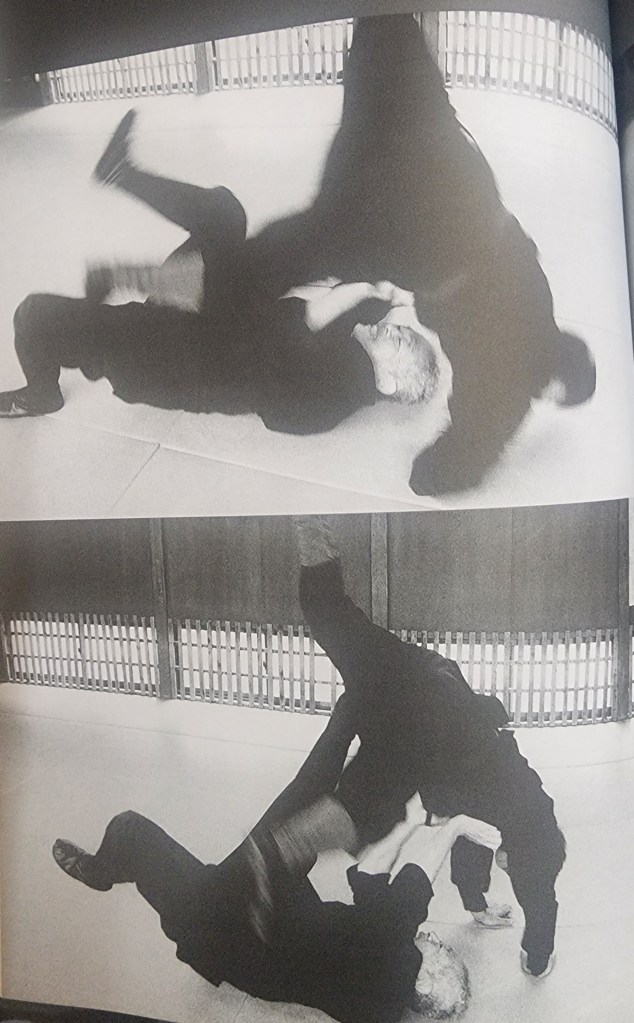

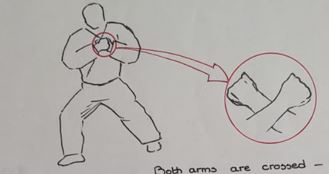

In the Bujinkan system of martial arts, when we practice with either the yari or the naginata, it is fairly common to strike the opponent with the rear end of the weapon. In a European context, with a pole axe, which is generally shorter than spears and halberds, the spike at the rear end is used quite often. So, it would be no surprise if the spike at the end of a Trishoola was used in a fight.

A poleaxe with a cladding or sheath or pommel on the rear end, encircled in white. This would be a Hirumaki.

A closeup of the Hirumaki equivalent on the poleaxe from the previous image.

But in the examples I shared from Japanese and European history, the spike at the end of a pole arm is not, as far as I know, the part of the weapon executing a kill. In this sense, the depiction of the spike at the end of a Trishoola being used as the primary weapon is very interesting, if not unique, especially since there are so many of them!

A wonderful demonstration of the use of the poleaxe in a duel. The poleaxes used here have a spike (Ishuzuki) at the rear end, not a Hirumaki.

Could this mean that the Trishoola really had two primary weapons? Was there a spear head at the other end of a Trishoola? And if there was, how was it wielded? And how was the weapon managed and rested while on campaign? Was there a protective sheath/scabbard for either or both ends that was taken off only during fighting, to protect them from the rain, mud and other elements? I have no idea.

Beyond all this, how was a Trishoola used in a fight? Be it a duel or a battle? And was it used often? Or at all? I am not aware of any manuscripts or set of carvings that give us an idea about fighting with a Trishoola in a historical context. Could it be that the spike was the weapon and the trident the defensive part of the weapon? This seems counterintuitive to a modern Hindu mind but need not be ruled out entirely.

The depictions of the Trishoola in the Mahishāsura Mardhini I have referred to are from a period when urban life was prevalent in large parts of India and cultural expression was thriving. Wars were being fought in all parts of the country as well. The trident beyond being associated with Lord Shiva in India and Poseidon in Greek mythology, does see use as a weapon in history. In ancient Rome, the gladiator of the type Retiarius did use a trident as a weapon, even if this only shows that it was used in duels & games, and not in battles.

So, the Trishoola as depicted in the hands of Devi Durga slaying Mahishāsura is indeed a weapon and not just a hunting/fishing tool. This makes the Trishoola and its use in combat, because we know so little about it, simply fascinating! Wish you all a Blessed Vijayadashami!