What is waza or technique or a form? We shall try to understand what that means with the following musings.

We have now trained with many teachers. We can, if we are regular students, over time, generally see a pattern that any teacher uses. This reveals to varying degrees the different types of practitioners of the martial arts.

Some express their learning by exploring the minutiae of the basic forms and apply all advanced concepts to those forms as well. The exploration generally is a consequence of applying the newer concepts to the older forms.

Others express their learning by expanding into other martial art forms to experience the feeling in those. Could this help them see their core martial art “from the outside”? Does it give them a fresh perspective? Or perhaps the core martial art form they train inspired them to try new things and art forms. Is this perhaps the same as applying new concepts to old forms? After all, the forms in other martial arts are also old, as far as their origins go, even if they are not the “old forms” that one trained when he or she started.

Here, we need to remember that the “core” martial art itself need not be the one you started with or the one you train most or the one you picked up last. That is a personal choice which need not remain static.

Still others teach the martial art form to different demographics, like children or adapt the teachings of the martial art form to women’s self-defence. They relearn other fighting forms and there is a free flow of concepts to and from all the martial art forms they train. They might do this by reading the new concepts being taught as a consequence of repeating the old forms incessantly. They may also choose to apply the new forms to varying speeds of training (in terms of faster or slower attacks), varying “intent” behind the attack and defence (harder/deeper strikes). Over this variation they layer the newer concepts to derive a new experience and learning for themselves.

There might even be those who remain students by being pure followers, simply consuming what is taught in class after class and leaving to the “act of following” any evolution they might undergo in their martial learning.

Many others, by dint of having a background in the defence services or law enforcement, see similarities in the way martial movement is similar in the old forms and the modern application. These practitioners experience and assimilate the new concepts differently from those without a similar background and their application of the new concepts does not seems to directly flow to life situations. It is first filtered through their modern martial experience and then applied to life situations.

There are also individuals with backgrounds in medicine, sports and its support ancillaries, and the mind sciences whose initial learning of the old forms itself is coloured by their experiences in their respective professions. The newer concepts always have to go through this experience first, to be assimilated. Thus, it is flavoured at first contact perhaps?

There is yet another class of practitioners, who might be literalists. These practitioners reverse the assimilation process. They apply any learning to life situations first and from there make the martial movement itself an analogy of the situation. For these folk, the learning is almost like a practical class in a “self-improvement” book, with the martial art class being something akin to a game played in an induction class in a multinational corporation. The objective of the martial art form here is material and esoteric grain/growth. With newer concepts being taught, the older forms disappear in their once recognizable avatars. They morph into something used to purely represent a concept.

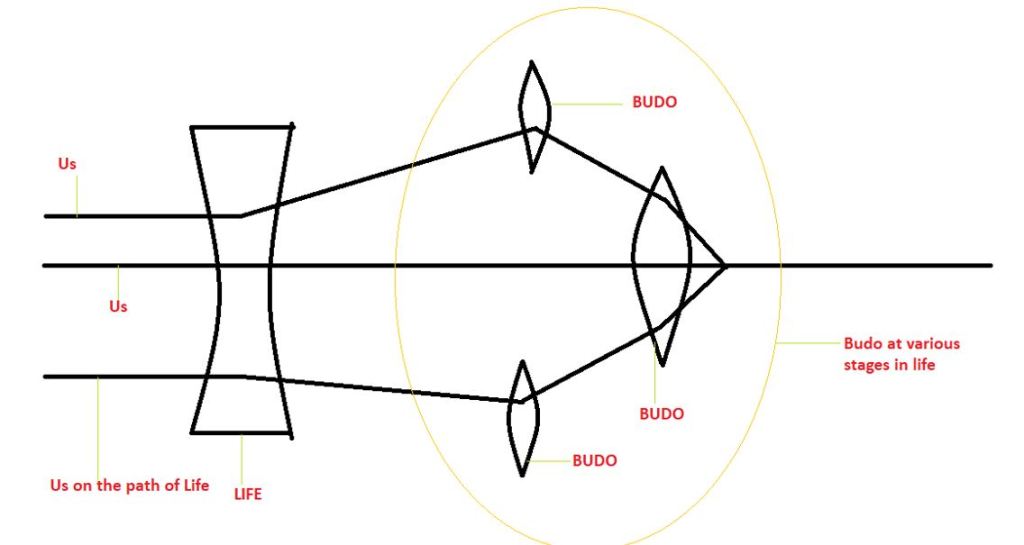

Thus, we have a whole gamut of practitioner methodology. Each of these affects the way any martial art technique is demonstrated. The form is like any story transferred through time and space. The rendering changes with each translation into a new language. Similarly a form or technique evolves ever so slightly in each transmission.

The variations in the transmission is due to the points focused on by the practitioner/teacher. This in turn is due to the background and method of practice and assimilation of the teacher as we have seen above.

This then leads to a wonderful array of options for students to pick teachers from, based on their own lives. The student may eventually become a teacher and the cycle continues.

Finally, the technique or form then is what was transmitted and assimilated between two individuals in a given place at a given time. It evolves with each rendering and transmission and while the name might remain the same, its appearance and essence (essential focus, key point) changes consistently. This is not very different to an individual changing with growth over time, the name remains the same, the person does not.

The frequency of change depends on the number of practitioners and their growth in turn. Over a long enough period of time, the same set of forms might leads to a whole new school of martial arts altogether. This is just like new species are created with small mutations and very little difference in DNA (humans and chimpanzees for example).

Thus, the form is not something written down in an old book (or a new one), it is what an individual expresses those words as. The form or technique is not something that exists by itself, the form is the person, with all the wonderful strengths and frailties that come with the individual.

The fact that the form or technique is the person is perhaps why grand-masters of schools eventually teach their oldest and most accomplished students concepts that border on the esoteric. They seem to realize over the course of their lives that they need to create a better human to improve the form, and to filter out all that they might seem malicious in the form (person) to lead to a better art form.

This perhaps is because in the case of the martial arts, unlike many other knowledge and arts systems, we deal with weapons, the weapons being the individuals themselves.

We always have to understand who we will use any weapon against. Everyone agrees that a weapon is to be used against an enemy. The hardest thing in life is to determine who the enemy is. There may be many things or people we dislike over the course of our lifetimes, but these do not constitute our enemies. Many of these do not play a part large enough in our lives to affect us to any great degree. They are just irritants, not “enemies”. Enemies are those that affect our livelihoods and our loved ones in a negative manner.

Conversely, it is always a lot easier to identify who we love (deeply care about, admire, respect). The ones we love, we can’t do without. They are our fuel. Also, we as humans might take the ones we care about most for granted. This in turn is seen when the ones we can’t do without change over time. We would love for our loved ones to remain their selves as we love them best, irrespective of how we change. This is not wrong, just human nature. When the ones we care about change for any number of reasons, we can no longer take them for granted, and that does indeed affect our livelihoods. This makes CHANGE ITSELF the enemy. But since CHANGE is non-corporeal, the ones we love might morph into the ENEMY.

This is not an enemy one wants to destroy, just one that should be prevented from changing. Thus, the WEAPON, the MARTIAL ARTIST might really get turned against the ones he or she cares about, to ensure a lack of change, which is JUST A MARTIAL ARTIST WANTING TO BE IN CONTROL of something other than oneself.

We need to bear in mind that the martial artist is not a weapon because of just the physical damage he or she can cause. Martial artists can cause tremendous psychological and intellectual damage due to their training. The transmission method they use with students and interaction methods they use with others due to the points of focus in their training of the forms itself becomes a weapon.

An example here can be planting a specific behaviour in students either consciously or unconsciously that might influence their lives in a detrimental manner (much like a cult does). A student might be conditioned with training to jump when the teacher lifts the finger. This only means that the teacher has to be supremely careful of when to lift a finger, not that the student is the master’s slave looking out constantly if a finger is raised.

The same is true in dealing with non-martial artists, if one sees them as inferior or as targets to experiment on, especially if the martial artist lacks empathy in training the forms.

Thus, in conclusion, waza or technique or form (in their multitudes) is a series of experiments by one upon oneself with the aid of fellow practitioners, teachers and students to hone themselves to continuously adapt to change (with the ability to empathize with one’s surroundings being a part of the adaptation to reduce conflict).

Before I end this article though, I have to add a little detail. This last aspect relating to psychological effects, in my opinion, is especially important in the Indian context. Due to our culture, traditions and our past, a teacher is always put on a pedestal in our lives. This is something that is ingrained in us from the time we are kids, in school and in the stories we are told. This continues through college and to the various people we consider teachers or mentors even much later in life.

In school, we start every day with a prayer* which states that the Guru is Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva (Maheshwara) and Parabrahman and that we offer salutations to the Guru. Of course, “Guru” can be more than just a “teacher”. A Guru can be a mentor, guide, teacher and even equivalent to a parent. When the Gurukula system existed, the teacher was indeed a parent for most of one’s formative years and hence one owed one’s character largely to the teacher. In modern day living, a Guru can be simplistically translated as a “teacher”.

Due to this great reverence for the teacher, the tendency for students of any age to blindly trust the teacher and do everything as stated is great. A student finds it incredibly difficult to disagree with or to say NO to a teacher regarding anything. In this situation, if a teacher is not aware of his or her responsibility to the student, or plain flippant in what her or she states, the potential for causing damage to the student is very high. Hence, “awareness” of every student and the effect one has on her or him is vital for a teacher, including in the realm of martial arts.

If the teacher is raised with Western culture where this relationship between the teacher and the student is not same, this risk is exacerbated. The teacher needs to make a strong effort to first learn the culture of Indian teacher-student relationships before he or she can set out on the journey of teaching Indian students. Beyond this, the teacher needs to always have awareness of one’s own methods in perpetuity, at least with respect to how to it is affecting her or his students. This is a part of the responsibility, whether or not one likes it. It is a consequence of being a martial artist, a weapon and a human.

Notes:

* The prayer, or more appropriately shloka, I referred to earlier is seen below.

Guru Brahma, Gurur Vishnuhu, Gururdevō Maheshwaraha

Guruhu Sākshāt Parabrahma, Tasmy Shree Gurave Namaha

A translation to the above shloka, as I understand it, is seen below.

The Guru is Brahma, The Guru is Vishnu, The Guru is Maheshwara (Shiva)

The Guru is the Brahman himself, I offer salutation to this Guru

[…] * https://mundanebudo.com/2024/01/04/a-myriad-of-methods/ […]

LikeLike