In large parts of India, among Hindus, touching the feet of elders and teachers or bowing down to them, is a common practice. It is an extension of bowing down before the Gods and Divinities. When I say bowing down, it is not the Japanese bow, or one seen in a historical European context.

We do what is called a “Shāstānga namaskāra” or “Dheerga Danda namaskāra”. Men do a full prostration in front of Divinities. Women sit on their knees touch their foreheads to the floor in front of the Gods. The same is done in the presence of our Gurus, some teachers and elders in the family, community or society based on the situation.

Two depictions of the “Dheerga Danda Namaskaara”. Image credits – (L) “Mahabharata 23 – The Twelfth Year”, published by Amar Chitra Katha, (R) “Mahabharata 20 – Arjuna’s Quest for Weapons”, published by Amar Chitra Katha

Touching the feet is not something generally performed with the Gods. This is done mostly with humans we revere. In this case, one bows down and touches either the feet or the ground in front of the feet. This is an abbreviation of the prostration described earlier, performed in the interest of space and time. A further simplified version is just bowing down and touching the knees of the person*.

Irrespective of the exact nature of the “bow”, the act denotes showing respect to the Gods or to the person before whom the same is performed. It is not exactly an act of deference or subservience, it is purely one of respect, and maybe bhakti (loosely translated as “devotion”). It could be an act of deference, but that was not, as far as I know, the original intent and is not the intent in most parts of modern India today.

The key point of the “bow” is to touch or be in front of the feet of the individual(s) towards whom respect is being shown. The Feet are, in this sense, the most important aspect. This extends to the point where we consider the ground that is trod by the feet of great people and Gods as sacred ground.

It was common practice, perhaps it still is, for elders who accompany younger folk to any temple, to tell them to look at the feet of the idol of the deity. This is a constant reminder and is passed on from generation to generation. In Kannada, it is called, “Paada nodu”. In Hindi it would be, “Pair dekho”. It literally translates to “look (nodu/dekho) at the feet (paada/pair)”. In this vein, touching the feet is “Paada muttu” in Kannada and “Pair chuo” in Hindi. “Muttu” and “Chuo” translate as “touch”.

So, the focus of Bhakti and the act of showing respect always involves THE FEET.

The other field where the focus on the feet is vitally important is the Bujinkan system of martial arts; I daresay this is the case with all martial arts.

Among the first things that a student learns on starting in the Bujinkan is “Kamae”. “Kamae” could be considered “posture”, of the physical body. It could also refer to “attitude”, which is the “posture of the mind”, which in turn refers to displays or the exuding of non-physical aggression, confidence, fear and the like. For the purposes of this article, I am referring to the physical posture.

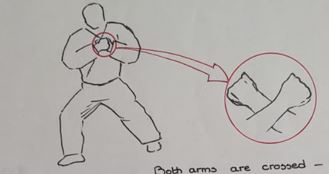

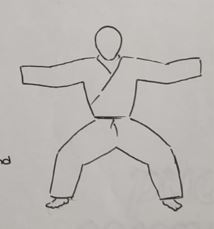

Two depictions of Kamae (physical posture). Sketches by Vishnu Mohan.

Kamae, when seen by an onlooker, predominantly shows the posture of the hands and the legs as a whole. But the kamae as experienced by the budoka (practitioner of budo), has greater focus on the core and the feet. The core because it holds the upper and lower halves of the body together. And the feet because it ensures balance and determines potential movements the body can perform, from said kamae. I will focus only on the key aspects regarding the feet in this article.

One of the key things that I have learnt from my teacher, mentors and seniors in the Bujinkan is that the weight should be towards the front half of the feet, i.e. towards the ball of the feet and the toes. The weight of the body should NOT be on the heels in any kamae. This holds true even for the most basic of the kamae, Shizen no Kamae, which can be translated as “Natural posture”. For those not in the know, this kamae just involves standing naturally in a relaxed posture.

Two more depictions of Kamae (physical posture), one with a weapon. Sketches by Vishnu Mohan.

The distribution of the body weight on the feet is absolutely crucial in the Bujinkan! To reiterate, it must be on the front half of the feet. This is vital because, making any movement from any given kamae, is faster with the weight on the ball and toes of the feet. Triggering any movement if one had loaded one’s heels is definitely slower. This is because the body is a lot more stable and rooted if one is standing on one’s heels. This in turn means that the inertia that needs to be overcome to initiate a movement is greater if one is on the heels.

When I say the “time taken to initiate a movement”, it is not too much, it could be a fraction of a second. But this time difference makes a definite difference during training and most certainly in a conflict situation that involves real harm. It could be termed “a split-second difference which makes all the difference”. This difference need not be distinctly visible to an onlooker, but any practitioner of the martial arts, certainly a practitioner of the Bujinkan, experiences this time and time again, perhaps in every class.

The distribution of the weight on the feet brings us full circle, back to the feet in Hindu culture. Specifically, to the depiction of the feet in sculpture produced by Hindu culture.

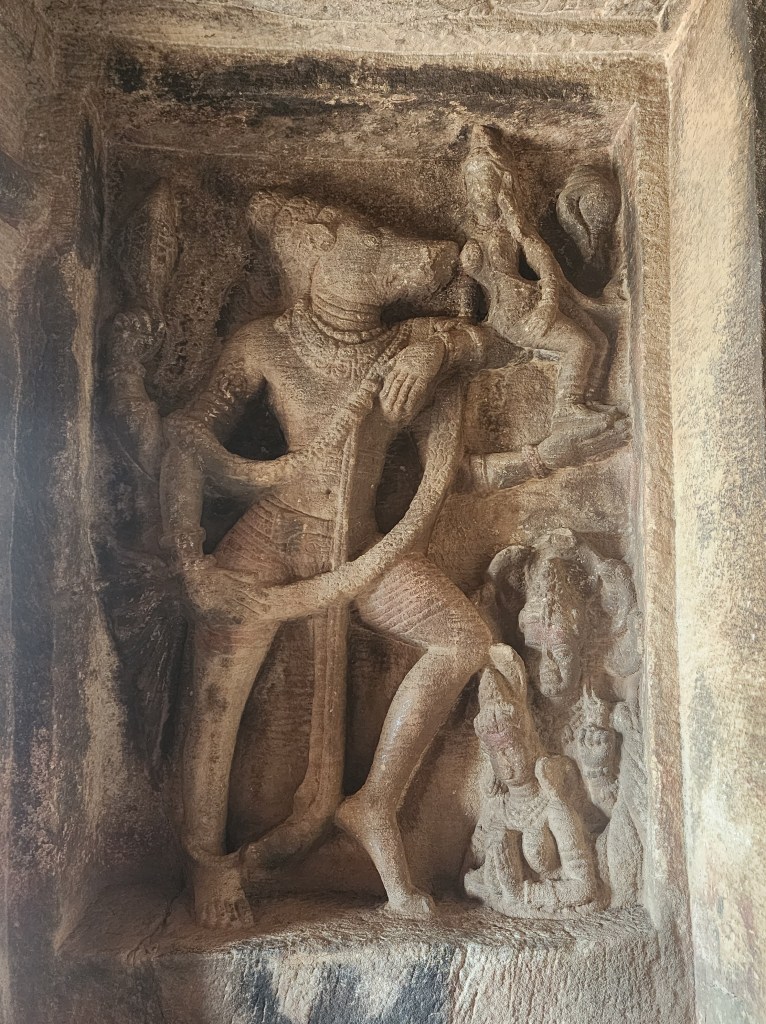

Lord Varaha saving Bhoodevi – carving in Cave 3 in Badami, Karntaka, India. The image on the right is a close up of the feet in the image on the left. Observe that the weight is either on the front half of the feet or on the side of the feet. Photograph by the author.

Consider any architectural or sculptural marvel from Indian history. It could the temple in Madurai, the sculptures in Mahabalipuram, the carvings on the magnificent temples at Halebeedu, Hampi or Badami, the marvels at Ellora or the historical monuments around Sanchi and Vidisha, or the many many others I have not mentioned here. All of them depict stories from Hindu culture. These include stories from the Mahabharata and Ramayana and the deeds of Lord Vishnu, Lord Shiva and Devi Durga. Many sculptures and bas reliefs depicting these stories show the human form in martial action. This includes the use of weapons and unarmed combat. Apart from the stories themselves, almost all temples have guardians carved on either side of the entrance to the Garbha Griha (literally “home or abode of the womb”), or sanctum sanctorum. These guardians always bear weapons.

The image on the left shows Lord Shiva destroying the Asura Andhaka (Aihole, Karnataka, India). Observe that the body is leaning forward and hence the weight will be on the front half of the feet. The image on the right from Pattadakal, Karnataka, India, shows a “Dwaarapalaka” (Guardian at the door). Observe that the individual is leaning on the weapon (mace/gada) and the weight is either on the front or the side of the foot. The weight of the body is not on the heels in either image. Photographs by the author.

Now consider the depiction of the feet in the sculptures showing martial action. Almost all of them show the body weight on the front half of the feet, irrespective of the kamae or posture depicted in the sculpture. This also extends to the posture of the guardians at the doorway to the Garbha Griha. Individuals might be shown leaning on the weapon they wield but are never depicted with the weight on the heels.

I am sharing multiple images with this article, that show the posture of the feet from a few different temples. One of them even shows the crimping of the little toe when the foot is lifted as if in a potential axe kick!

The image on the left, from Cave 3 in Badami, Karnataka, India, shows the Trivikrama form of Lord Vamana. Observe that he is standing on one leg. The image on the right is a close up of the left foot in the image on the right. Observe the crimping of the last 2 toes, as the weight is distributed to the front and side of the foot. Photograph by the author.

It is well known that temples in India have historically been more than just places of worship. They have been cultural centres, malls, schools/training centres, banks and treasuries, apart from just places of worship. The carvings on the temple walls were intended as teachings and storytelling features, sometimes both. Everything from tales from history and ethics to practices of intimacy were carved on temple walls. This was, according to some, because a lot of this knowledge was not taught directly.

Temples were thus a means to learn what was not yet in books and was not taught specifically as a subject in schools. So, considering this intent, in my opinion, what is carved in the temples are depicting what is, in all likelihood, the correct way one is supposed to load one’s feet. Therefore, the depictions of feet of warriors, even if they are deities, is showing how the weight distributions on the feet works, in marital arts in India.

The image on the left, from the Ravanaphadi Cave in Aihole, Karnataka, India, depicts the Mahishaasuramardhini. The image on the right is a closeup of the left foot of Devi Durga. Observe that weight is clearly on the side and front of the foot. Photograph by the author.

This continuum of importance of the feet and more importantly, the weight distribution on the feet is awesome indeed, at least to me. If one is a Hindu, it will be well known that feet are important to Bhakti and if one is a budoka practicing the Bujinkan the importance of weight distribution on the feet would be a key learning. The two come together in the depiction of the feet in sculpture seen in Hindu temples. Perhaps the best place for a budoka to appreciate the kamae of the feet is in a sculpture in a Hindu architectural marvel and being a Hindu, it is impossible to miss the kamae of the feet, for the feet is what one is culturally conditioned to observe. An absolute win-win combination. 😊

Notes:

* When a person touches the feet of another, the person whose feet is touched, almost always offers āshirwāda, which can loosely be translated as blessings. So, there is a responsibility placed on the person receiving the respect. It is not just to foster an air of superiority. A person being shown respect must have the humility to know that āshirwāda is due, even if not expected.

A good comparison between Hindu customs and martial art with ample photographs

LikeLike

Thanks a lot!

LikeLike